Who says Kassel is boring? In 1972, Joseph Beuys drew Harald Szeemann’s documenta 5 to a close — and with it the Office for Direct Democracy (1972), Beuys’s renowned space for political debate and deliberation with Kassel audiences — with a celebrated, carnivalesque face-off in a boxing ring. Forty-five years and nine documentas later, Kassel finally played host to another boxing match, though this time not a playful shadow-punch between artists in the presence of the über-curator. Beuys the teacher duked it out with local art student and upstart Abraham David Christian, the former fighting for ‘direct democracy by referendum’, the latter for ‘representative democracy’ (the teacher won on points). Now the fight is for documenta’s very future.

As the overstretched string of curators and ‘chorus’ educators, advisors and assistants, led by artistic director Adam Szymczyk, readied themselves for documenta 14’s withdrawal, and the columns of contraband texts came down from Marta Minujín’s reconstructed The Parthenon of Books (1983/2017) in Kassel’s central Friedrichsplatz, Kassel’s local newspaper delivered a bombshell. 01 The Hessische Niedersächsische Allgemeineannounced that documenta’s parent company, documenta und Museum Fridericianum gGmbH, was approximately seven million euros in deficit. This was, apparently, the result of expanding Kassel’s usual ‘hundred-day event’ into a 163-day, 82-venue feat of endurance across Kassel and a second location, Athens. Kassel’s municipal council would step in to save documenta, while Szymczyk and documenta gGmbH’s then CEO Annette Kulenkampff, 02 were rapped over the knuckles for breaking the exhibition’s 37 million euro budget by nearly 20 per cent. 03

The curators’s response was swift and blistering. documenta 14 was a ‘collective and transnational’ enterprise, they claimed, and therefore ‘beyond the mechanisms of local, regional and national identities and the funding associated with them’. 04Even if it were bound by those mechanisms, documenta’s ‘stakeholders’, including the German state and documenta gGmbH (now seemingly thrown under a bus), knew what they were getting themselves into when they chose Szymczyk’s proposal back in autumn 2013. Furthermore, even if awareness of documenta 14’s ambitions did not excuse its budget overreach, documenta needed to maintain its ‘independence… as a cultural and artistic public institution from political interests’. The time had come, the curators declared, ‘to question the value production regime of mega-exhibitions such as documenta’. 05

Various documenta 14 participants chipped in the following day, denouncing the municipality’s castigation of the event’s team as a means of ‘[s]haming through debt’, taking ‘documenta’s long heritage of decentring… and decolonising’ contemporary art and fouling it through ‘a neoliberal logic’. 06 ‘Receiving the world, as equals, contrary to anxieties’, the participants wrote, would not only challenge that logic and all that informs it, from ‘heteronormativity’ to ‘the poisoning of the planet’; it also, the artists asserted, ‘contributes to radiance’. 07 It would be easy to dismiss the two responses as strikingly naïve and even disingenuous. If ‘radiance’ – whatever that might mean – is not quite the most strident challenge to neoliberalism I’ve encountered, one would think that a sense of ‘radiance’ might still be possible to generate within 37 million euros, a sum that’s all the more vast given the financial ruination of Greece. 08 While the curators argue that documenta’s overseers knew the challenges ahead of Szymczyk’s accepted proposal, that retort doesn’t dispel the similar counter-claim that the curators knew the budgetary parameters going in. As Szymczyk’s introduction to The documenta 14 Reader spells out, documenta gGmbH’s five-year budgetary plan was ‘[m]ade in 2012 and based on the budget of the previous documenta [such that] it did not allow for a very substantial part of the upcoming iteration of the exhibition to take place far away from Kassel’. 09 (Indeed, Szymczyk’s introduction, written between November 2016 and January 2017, pre-empts nearly point-for-point the sparring arguments played out eight months later – the demand for increased audience numbers, the threat of political acquiescence to state and corporate sponsors, the fear of ‘debt as political measure’ – more than hinting at the spectres already haunting Szymczyk’s ambitions.) 10

It’s tempting, then, to see documenta’s near-collapse as once again a redolent symbol of its times: of this great post-war vision of a renewed Europe, of a Europe snuggled deeply within a North Atlantic embrace, brought to the brink at the same time as that particular Europeanist dream trembles with fear and despair.

It’s just as easy to note the discomfiting symmetries between documenta 14 and austerity-ridden Athens, the city from which, as the exhibition’s working title notoriously espoused, lessons could be learned. There was more than a bitter irony in the morality play of indebtedness imposed on Greece now imposed on documenta for venturing to Athens. That situation was made all the more tart by the German state’s willingness to bail out documenta, yet refusal to pardon Greece’s debt. What strikes me as just as discomfiting, though, is the belief that documenta is, as an institution with a 60-year rich history, somehow above and beyond such political game-playing by what used to be called ‘the centre’, as though documenta – like the romanticised notions of artistic and critical autonomy made in the two e-flux statements – were somehow free from the challenges and accountabilities of such grubby things as money and power. That perception of documenta is a fantasy.

Rather than politically independent of the state or an exemplar of ‘decentring… and decolonising’, much of documenta’s history reveals it to be a proud bellwether of the aspirations and concerns of the North Atlantic region. documenta’s founding by Arnold Bode and Werner Haftmann in 1955 was an explicit attempt to re-evaluate abstraction and other ‘progressive’ markers of modernism as the pinnacle of contemporary culture, following its denigration as ‘degenerate art’ by the National Socialists. However, that celebration of modernism was just as much a celebration of the capitalist North Atlantic and post-war West Germany’s place within it. Not only were many of the artworks in the first documenta available for purchase through the exhibition-cum-marketplace, but those works were by artists firmly based in Western Europe or North America. 11 Not a single artist based outside Western Europe, bar the three from the United States, was included in the first documenta, with numbers from the US increasing steadily through the Bode years up to documenta 4. Indeed, the overwhelming lack of artists not based in the North Atlantic region continued in Szeemann’s documenta 5 – perhaps the pinnacle of North Atlantic exchange if not triumphalism – and persisted right up to Jan Hoet’s documenta IX in 1992. The more expansive geographies and practices offered by Catherine David’s documenta X in 1997 and Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta11 in 2002 are significant correctives to that history. Yet, we would be more accurate in calling them forms of belated feedback on documenta’s status as a North Atlantic powerhouse, with its increasingly multicultural composition testament to the similar make-up of Kassel, and Germany as a whole, and marked by the ideological shift from espousals of freedom to rhetoric of openness. 12

One of documenta’s distinctive aspects, then, is that it missed almost entirely the much broader international experimentations and collaborations offered by what Charles Green and I have called the ‘second wave’ of biennials between 1955 and the 1980s. Those were large-scale, generally state-funded international exhibitions based in cities aligned with nascent Third World politics. 13 From Ljubljana’s first graphics biennial and Alexandria’s first Mediterranean biennial both in 1955, through the later editions of Tehran’s biennial, 14 or Delhi’s triennial of contemporary world art, 15 these exhibitions looked far beyond the North Atlantic for their participants, audiences, and politics of exchange. They revealed that other trajectories of art history and art practice could be delineated precisely by not looking to documenta as a model. These biennials would, in turn, influence the scope of other exhibitions within the North Atlantic, especially those that, like their second-wave counterparts, were initiated and funded by the state. The first edition, in 1959, of the Biennale de Paris, for instance, showcased artists from Eastern Europe, Latin America, west Asia as well as the North Atlantic, with many of these artists working across abstraction and figuration, both in traditional and more experimental media. If we want to talk about ‘decentring… and decolonising’ exhibitions, this is the lineage to recognise. To speak of perennial exhibitions being somehow independent of political interests, however, particularly those of its local funders and their international aspirations, is for the most part another misnomer altogether.

This is not to say that we can or should dismiss documenta’s significance, of course. As North Atlantic bellwether, documenta offers very useful insights into what most interests or threatens the creaking geopolitical hegemon of yore: whether that be concerns about a self-congratulatory insularity,16 or about environmental degradation and a yearning for greater sensitivity towards the non-human. 17 In this regard, at least, documenta 14 follows on neatly from its predecessors, for it too offers useful insight into the state of (part of) the world. What it suggests, though, is a state of deceptive conservatism and even deeper confusion in a North Atlantic that is clearly the primary audience of documenta 14, an exhibition that strikes me as one of the most Euro-centric, perhaps even German-centric, documentas in years.

I say this not because of the backgrounds of the artists or the participants or even the curators involved, but because of documenta 14’s audience address: its sense of a we despite all the assertions made about documenta taking ‘a decidedly anti-identitarian stance’, or the insistence on ‘unlearning’ as a means to become a political subject. 18For who is meant to learn from Athens? It’s certainly not the city’s residents, who know all too well what the last eight years of eroded sovereignty and savings have done, let alone the fragile legacies of a large-scale international spectacle. 19 Nor is it the 1.6 billion residents of East Asia, given the near-total exclusion of any artists from or based there. Again, Szymczyk’s introduction to the Readermakes his point clear: his audience is ‘[t]he collective and historical “we” of Western civilization [and] our unstoppable conquest of territory and insatiable hunger for the dissemination of “our” ways of being’. 20An important and earnest rejoinder to the colonial and neocolonial impulses of much of that ‘civilization’, certainly, but it ignores how much of Kassel’s inner city and north – let alone much of his Athens audience, whether local or jet-setting – is rich in immigrant populations who might have quite a different relationship to this exclusionary we of Western knowledge, history and belonging.

Perhaps we need to step back a bit, though, and pose a different question: not who is meant to learn from Athens, but what might we learn? Here, another problem arises, for the signifier ‘Athens’ comes to mean many things at once in this documenta. It’s a synecdoche for Greece given the damage wrought across the country, and not just its capital, by the troika and the country’s ruling elite. It stands for asylum and the influx of refugees seeking passage through Greece to the rest of Europe, most notably Germany.21 It symbolises the birth pangs of art and art history in the North Atlantic, 22 as well as the foundations of democracy, as curator Candice Hopkins and others suggested at the Kassel press conference. Indeed, democracy may well be Greece’s greatest gift to the North Atlantic, albeit one that the North gifts to others now more through war than by example (and let’s not start on the exclusion of women and slaves from the vote in Hellenic antiquity…).

That’s not all that the notion of ‘Athens’ is made to represent through this exhibition. It stands equally for resistance to austerity and exploitation of the many by the few – for the anarchist energies of Exarcheia, the downtown neighbourhood where the people of Athens began their resistance, and thus for the very possibility of uprising today. Most of all, it comes to embody all things ‘South’, itself a term used increasingly to cover a loose spectrum of experience and expectation: at once the new ‘East’ and the new Third World; a space of poverty and war from which people seek to flee; a space of exploitation and possible resistance to it; a deus ex machinafor we North Atlanticists wanting a different but easily nameable politics; and most tellingly, a ‘state of mind’, as branded by the Athens-based journal that documenta 14 inhabited for four issues from 2015 to 2017, like an attitude, a whim or a breeze. As such, the signifier ‘Athens’, much like that of ‘South’ in recent years, risks becoming a marker of overload. It is so porous and all-encompassing, so inherently contradictory yet ostensibly meaningful, that it is ‘simultaneously too empty and too full’, as Stuart Hall once claimed about another encumbered term, the contemporary ideology of democracy. And much like Hall’s understanding of democracy, documenta’s vision of Athens has become ‘so loaded down with ideological freight, so indeterminate… that it is virtually useless’. 23

There are two main problems with this overloaded signifier of Athens, especially given the constrained us the exhibition seeks to address. The first relates to a morality play about indebtedness; the second to the instrumentalisation of artworks at the expense of a more sensitive engagement with context. Let me explain each in turn.

The first problem – about moralised indebtedness – was arguably most evident in Kassel’s Neue Galerie, the main German venue for this edition (if only according to the length of the queues wanting to enter it). The museum’s first room, dedicated squarely to begging, set the scene. Stills from Tomislav Gotovac’s 1980 performance as The Begging Artist shared space with quattrocento paintings of Saint Anthony tempted by gold, as well as Gustave Courbet’s drawing of an Ornans beggar seeking alms, together with other historical and recent works on the theme. From there, audiences were channelled into room after room of works framed through indebtedness. A historical section showed depictions of Athenian ruins by Bode, Louis Gurlitt, Theodor Heuss, and others, alongside a German School portrait of Winckelmann in a classical (albeit Italian) landscape. It was not too difficult to identify what presumably Germany owes Greece: its art-historical traditions, its understanding of landscape, its post-war political aspirations, the very existence of documenta.

Other conflations of debt and indebtedness abounded further along. Encased in a vitrine sat a copy of the 1685 Code Noir, France’s laws regulating and advocating slavery in Saint-Domingue, from which it profited greatly. Further back still was another vitrine containing a copy of the agreement, signed in London in 1953, which relieved West Germany of its post-war external debts. Germany’s windfalls from Nazi looting of Jewish homes – figured most impressively by Rose Valland Institute, Maria Eichhorn’s long-term research project seeking the documentation and restitution of stolen Jewish property – fed into displays haunted by other episodes of murder, pillage and contemporary expropriation: from the relics of colonial theft not repatriated (such as Munich’s Benin Bronzes or the Congolese textiles and pottery in Danish collections, now part of Sammy Baloji’s series Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues (2017)) to the dangling heads of Nazis and contemporary CEOs (in Sergio Zevallos’s A War Machine (2017)) and 203 images of ‘real Nazis’ (in Piotr Ukla´nski’s eponymous installation).

Handled well, as Eichhorn shows, these reminders of indebtedness can be smartly confronting. However, when treated as bombastically as they often are here – as with the collapsing of Nazism, neoliberalism, slavery and other atrocities – these reminders run the risk of replicating the very process of moralising through indebtedness that is one of the hallmarks of neoliberal austerity and its neo-colonial agenda today. That is, what such displays seemed to seek was to castigate people for being in debt, a mode of rebuke that Wendy Brown foresaw in 2003 as the infiltration of all forms of exchange (whether interpersonal or international) by financialised rationales and hierarchies of power.24 (Or, to use the language of the documenta 14 participants in their e-flux letter, a condemnable means of ‘shaming through debt’.) This replication of neoliberal methods and discourse may well be Szymczyk’s point, a way of speaking back to the enemy through its language of financialised moralism. It may also explain Szymczyk’s constant references to the exhibition’s participants and visitors as ‘shareholders’ and ‘owners’, the quintessential constituents of neoliberalism. Yet, in doing so, documenta 14 seems to accept that there is no alternative to the terms and philosophy that neoliberalism espouses today. It forgoes the need to find other ways to work through the past and the present. It relinquishes the need to find other methods of understanding and means of communication than those set by the agenda it supposedly seeks to resist. It doesn’t so much fight back as ventriloquise.

This first problem feeds into the second, which is a surprising and frequent insensitivity to the actuality of context. The exhibition’s contents tended to come off poorly under the weight of the curators’ thesis (or at least this part of it). Marshalled as evidence for the prosecution, works were treated less as artworks than as documents for a future that was unanticipated when they were made. Any depiction of Bode or drawing of Athens by Bode would suffice to represent documenta’s founding, just as any historical or contemporary work on begging could function in that front room. 25 It’s the theme that matters most and once works are instrumentalised in this way, they become interchangeable. Had documenta been able to display the Gurlitt estate of art collections stolen from their Jewish owners, as Szymczyk had originally intended, the works may well have suffered a similar fate: relevant less to the curators as artworks than as either evidentiary relics from a crime or visual witnesses to a crime. In a conversation with Eichhorn, Hans Haacke and Alexander Alberro, Szymczyk asked: ‘When those witnesses of some profound violence have died, can the works that remain… stand as a different kind of witness?’ 26 It’s certainly a pertinent question amid the need to repatriate objects (or artefacts or land) to their rightful guardians. However, whether evidence or witness, the artwork is treated the same way: as passive to the histories made around them rather than as active or transformative agents within history. Artworks don’t make or intervene in history, according to Szymczyk et al., but are simply marked by them.

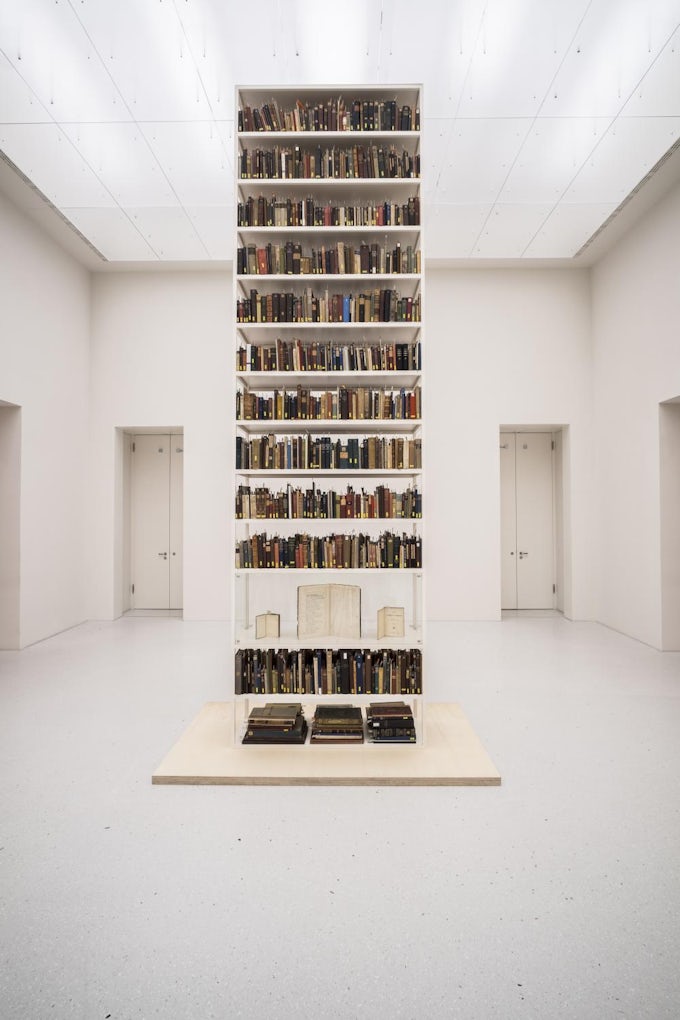

What is often missing, then, is an interest in the contexts of an artwork’s or a situation’s makingand what they can do from that context, and it’s a problem that recurred throughout documenta’s divided sites. One of the exhibition’s more striking touches was to recognise notebooks, letters and archives, as well as sheets of music, as scores through which the past can speak to or be replayed in the future. Yet, so often those scores were silenced by the vitrines that encased them, by the frequent presentation of writings and ideas in closed books, by the lack of activating what those scores did and may still do. A cabinet housing closed pamphlets of Rabindranath Tagore’s poems or fragments from the Visva-Bharati News can offer little insight into the energies propelling Santiniketan as a site of revolutionary political pedagogy in pre-independence India, just as dusty photographs, letters and notes by Cornelius Cardew limit a sense of what the Scratch Orchestra did that was transformative, or a closed copy of Richard Wright’s The Color Curtain (1956) becomes a mute object rather than participatory observations of the 1955 Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung and the birth pangs of non-alignment. At best – as with Jani Christou’s display in Kassel or an occasional workshop in Athens – sound filled the rooms in which the scores were displayed, so that other senses could rejoin the visual to give greater dimension to the dynamics, the enticement and the sheer inventiveness of their making. For the most part, though, these decontextualised objects were not scores resounding from the past. They were footnotes pointing back to them, earnestly but conservatively, their revolutionary potential still to be discharged.

That lack of contextualisation and curatorial innovation was nowhere more hampering, however, than in the cliché site-specificity that riddled the Athens venues. This was a crash course in Contextualisation 101: sound works and instruments in the Athens Conservatoire; works on radical pedagogy and the failings of traditional schooling (Santiniketan, the Halprins, Oskar Hansen, Allan Sekula) that opened the parcours in the Athens School of Fine Art; works about threatened libraries at the Gennadius Library within the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (pity the poor readers trying to work there while we visitors bumbled through), the list goes on. Such twee engagements with place were barely evident in Kassel: perhaps because of a greater familiarity and comfort with working in Kassel or perhaps in the knowledge that such clichés would be howled down by an all-too-knowing art crowd. That these types of engagements, or lack of them, should recur throughout the Athens displays suggests not only a discomfort or uncertainty with working away from home. It also dovetails with the perception of Athens not as a place of living and surviving, but a signifier, ‘Athens’, whose institutional venues can equally become mere symbols for key themes: sound, un/learning, archaeologies, Islam.

This is not to say that there weren’t fine works dotted through documenta 14, but those that sang had to struggle particularly hard against such curatorial suffocation. Some combatted the either/or divide between evidentiary object and visual witness by letting a different engagement with the past, a more active and potentially fictional inhabitation of ‘non-canonical’ histories, come to the surface. Particularly relevant here was Naeem Mohaiemen’s Tripoli Cancelled (2017) and its playful restaging of the entrapment of Mohaiemen’s father in Athens’s Ellinikon International Airport in 1977, while travelling from one country to another without a passport, caught in limbo within yet outside the nation-state’s parameters. As the actual nine days of his father’s isolation are fictionalised into years, absurdity enters the tale – the man’s boredom is broken up by dancing to Boney M in the crumbling empty airport, or by fondling the breasts of a mannequin dressed as an Olympic Airways (now Olympic Air S.A.) stewardess – such that this otherwise occluded narrative is made further estranged and surreal. Other works echoed recent pasts through modest gestures of intimacy laced with humour (rare commodities in large-scale exhibitions like this): most notably, the delicately embroidered narrations of asylum and violence in Mounira Al Solh’s Sperveri (2017), spun through sustained listening to people’s testimony of migration and their painstaking reworking through the artist’s needle and thread.

Now that documenta 14 has closed, however, it’s less the individual artworks that linger than hesitation about the sustainability of this leviathan institution. The Kassel municipality’s financial bailout will ensure documenta staggers towards its next instalment, despite all the repercussions and slanging matches. 27 documenta gGmbH’s alleged near-insolvency touches on a niggling concern throughout this edition of the event, though, and that is its disengagement with the future relative to its passions for the past. Part of this concern is what we might call the ‘Manifesta 3 effect’, given what happened in Ljubljana in 2000: the temporary anchoring of a large-scale international exhibition in a city in recovery mode, building little on the cultural and grassroots networks already there but extracting much of the financial and other resources that had kept those networks active. documenta’s stark lack of engagement with Athens’s lo-fi artist-run and street-art scenes, its disconnection from the concurrent Athens Biennale, even its relegation of the Athens School of Fine Art’s MFA degree show to a backspace left largely unattended by documenta’s stream of visitors does not augur well here. Nor does Athens’s hosting of firefly performances and workshops, most of which had flickered and ended long before the exhibition’s concluding week, leaving little trace bar some videos extracted and shipped to Kassel. Constructive infrastructural activism was clearly not documenta’s focus in Athens (despite this being the mainstay of its long heritage, its very raison d’être, in post-war Kassel). And while the participants’s letter rightly voiced fears about environmental degradation and ‘the poisoning of the planet’, this documenta stood in blunt contrast to its predecessor through the lack of works engaged with ecologies of any kind (whether planetary or infrastructural). Only Gene Ray’s two essays in South as a State of Mind offered thoughts on contemporary ecocide and its tethers to colonial genocide. 28 For Szymczyk, documenta was defined more by ‘163 days of constant journeying back and forth between these two somewhat distant (in all senses of the word) locations’, 29a claim as troubling for its carbon footprint as for its implied hierarchy of belatedness and progress.