Naima Hassan: Can you introduce yourself, and your relationship to photographic practice?

Leyla Degan: I am an Italian-Somali artist and researcher. My research and studies focus on archival photography, which is shaping the professional vocation I aspire to take. I have been interested in photography since I was young. My paternal grandmother introduced me to it, as she was the daughter of a photographer, my great-grandfather, and many of her brothers and sisters were photographers too. With her by my side, I was able to discover various aspects of photography, and I owe a lot of who I am today to my grandparents.

My father introduced me to the world of collecting and research. He is a meticulous philatelist, and I spent many long afternoons with him learning about it. As time went on, my interest in research grew, and I began to develop my own research practice. This led me to discover the power of archives in the preservation of history.

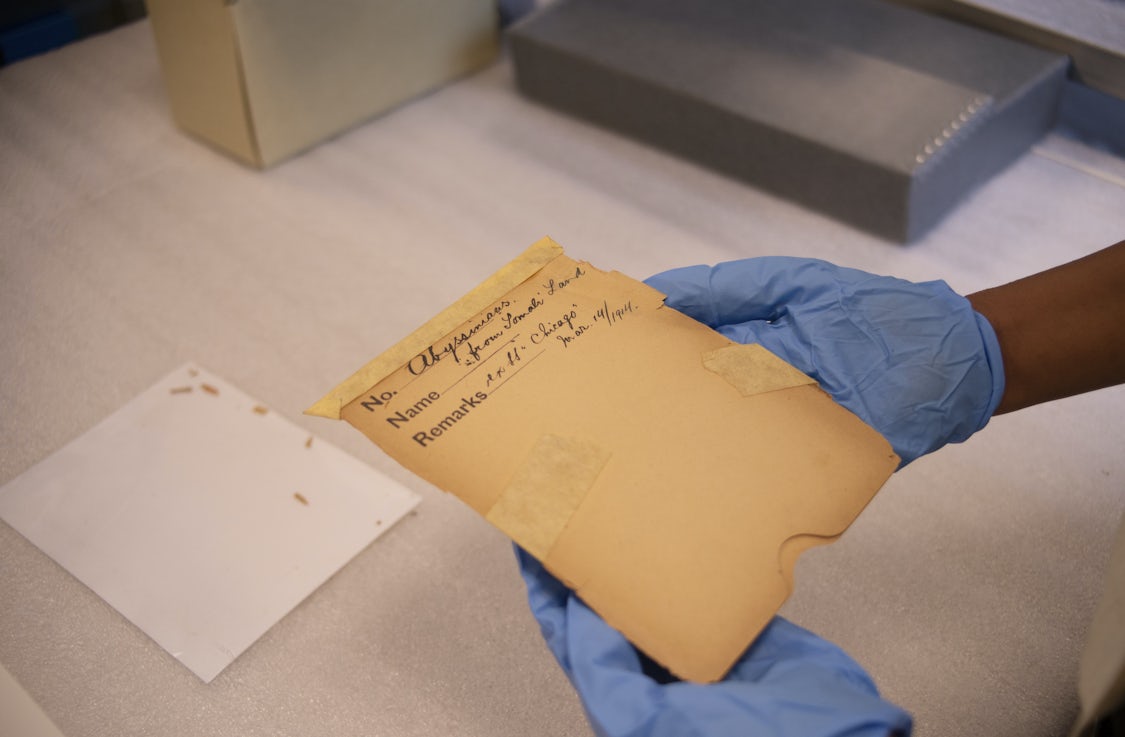

NH: Two months ago, we concluded the first outcome of Transmigrating Cassettes.01 I wanted to use this dialogue as an opportunity to reflect on how we came to a methodology for transforming a set of photographs and associated archives of a Somali troupe who were initially photographed by Ellis Island senior immigration clerk Augustus Sherman in 1914. As a photographer, what first drew you to cyanotypes?02

LD: I first encountered cyanotype photography through my master’s programme in photography archiving. I started doing some more in-depth research on cyanotype printing, through a historical and contemporary lens, and grew fascinated by the final tonality of the print which invoked feelings of security and stability. The different shades of blue have reconnected me to the sea, which has always been synonymous with protection for me. Secondly, I associated the use of this technique with a possible reorientation of my photographic practices, combining it with the work of research and study that I’m doing on Somalia. It was the best way to translate a part of myself under a new photographic sphere.

For me, it was important to create a space where I could use photography without haste. I wanted to go back to a more meticulous approach to photography, where timing plays a crucial role in achieving good results. The technique allowed me to connect with my body and search for protection and spirituality through a manual process.

NH: I was struck by a moment during the public programme for Transmigrating Cassettes where you invited workshop attendees to examine their family photographs using a microscope and colour scales used to identify types of photographs. The introduction of technical language and a device created a palpable unease within the space. By presenting these technologies, we become emissaries to techniques implicated in generating images of colonised subjects. These tools often served to articulate divergent or devalued manifestations of personhood. I am contemplating this baggage. Can you tell me more about this moment for you?

LD: Understanding photographic processes can be challenging for the general public. Many people believe photography simply involves reproducing an image on paper. However, the reality is far more complex. Photography is a nuanced and intricate art form that is often overlooked or undervalued. Despite its overuse in the modern era, photography is not given the attention it deserves. In our workshop, I wanted to offer participants some guidance on the most commonly used photographic techniques of the past. This will provide them with the tools and knowledge to recognize their own photographs and to be able to critically think about their own archives that hold such an important part of the history of the Somali diaspora.

NH: I was drawn to describing the cassettes and cyanotypes as ‘instruments of repair’ (a term I have employed to think about the potential affordances of contextualising Somali ethnographic objects in contemporary contexts). Sasha Huber’s series ‘Tailoring Freedom’ (2021) illustrates the potential of artistic experimentation within dark archives (charged colonial collections, ephemera, and photographs). The series attempts to ‘staple’ together different temporalities by altering the elements of the photograph’s composition: Huber ‘redresses’ unclothed enslaved persons captured in daguerreotypes, essentially creating a fugitive register between present and past. The cyanotype, like the daguerreotypes, carries its own baggage, particularly in the arena of colonial botany and plantation economies.

Within your personal cyanotype series ‘Ilaalin; Waan Ku Ilaalin Doona’ (2023), the Somali Xirsi (protection necklace) appears (figure 3). How do you aim to connect embodied interactions with the Xirsi with other forms of research?

LD: In this series, my approach was to establish a deep connection with the object and its significance within Somali culture. This relationship has acted as a guiding force in my introspective journey. The self-portrait as a motif continues to recur in my practice. It is as if I am submerged in water that reconnects me with the sea, and I am protected and guided by my roots: the Xirsi, in this case, acts as the protector and connects me to my mother and the maternal feminine sphere. The proximity of the Xirsi to my head acts as a beacon and a guide that motivates me to move forward. The length of my hair, which my mother always wanted to see long, represents strength and energy, the necklace that I have inherited reinforces my connection with her. Hence the title of the series “Ilaalin; Waan Ku Ilaalin Doona” that in Somali translates to “Protection; I will protect you”.

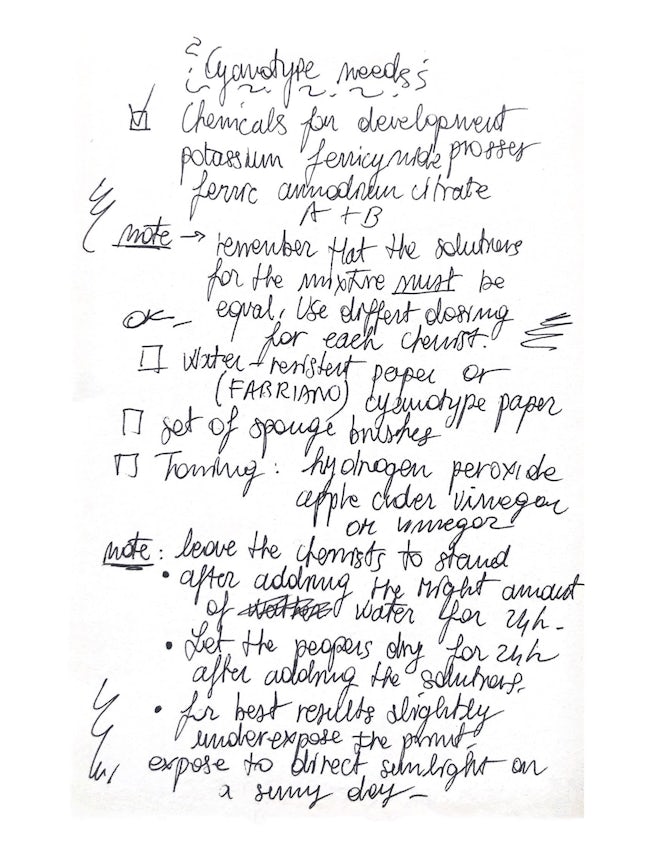

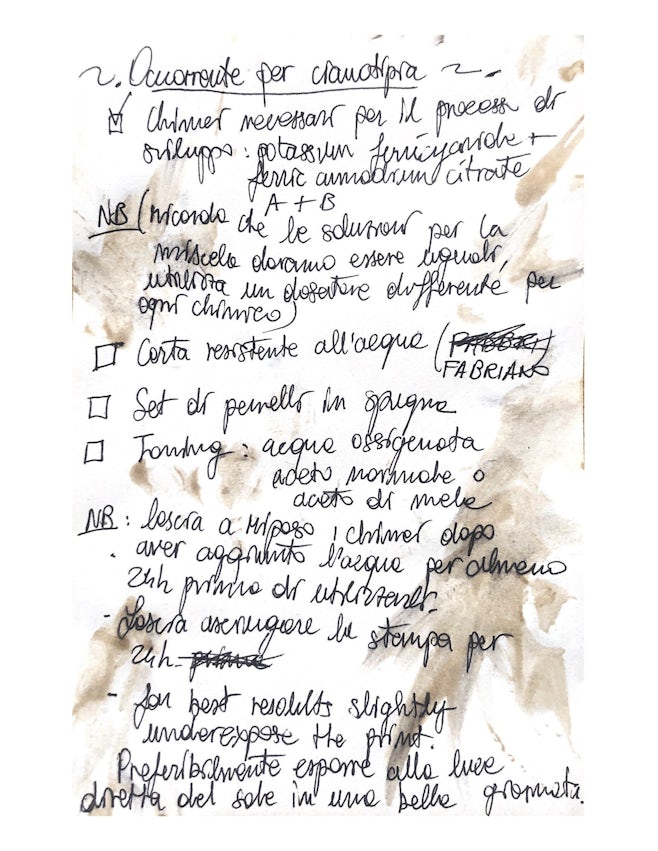

NH: Watching you develop the cyanotypes felt like observing alchemy. What steps were involved more practically? Perhaps you can share instructional methods?

NH: During our public programme, you spoke to our audiences about the significance of the hue of a cyanotype resembling the Somali flag. Chemically, this is the result of a photochemical reaction between two iron salts. Why might this be a significant entry point?

LD: The association between the colours of the Somali flag and the cyanotype was immediate for me. Even before starting my photographic series, I had already decided that these colours would reflect this connection. Although the true definition of cyanotype colour is Prussian Blue, which is quite different from the colour of the Somali flag, it inevitably reminds us of the Indian Ocean, which is represented in the Somali flag. Our project heavily relies on this association as a departure point and invitation. Returning to Sasha Huber’s series ‘Tailoring Freedom’ (2021), cyanotypes within our process afford dignity to the subjects depicted in the photographs.

-

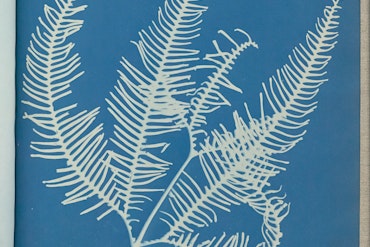

Figure 6. Cyanotype prints in Anna Atkins’ Photographs of British algae: Cyanotype impressions, Gleichenia immersa, Jamaica, 1853, Davallia aeuleata, Jamaica, 1853. Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum. -

Figure 7. Cyanotype prints in Anna Atkins’ Photographs of British algae: Cyanotype impressions, Gleichenia immersa, Jamaica, 1853, Davallia aeuleata, Jamaica, 1853. Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

NH: I wanted to visit the works of English botanist and photographer, Anna Atkins.03 Her seminal book, Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns, was developed through her association with Jamaican plantation economies. Her husband and father-in-law in fact owned eight plantations (figure 6 and 7). As archivists inhabiting the colonial archive, it should not be a surprise that the cyanotype has a colonial foundation.

During our public programme, we decided against producing a spectacularised narrative around the troupe. Instead, we committed ourselves to examining the subjectivity of the troupe alongside other communities of performers. In a future iteration of our public programme, I would like the cyanotype to be unveiled in a context that reveals its early entanglement with extractive colonialism. There seems to be a not-yet addressed question within the museological field. In Cape Town last year, and again this year in Lagos, I asked curators tending to Somali collections within their respective institutions, how do we care for one another’s cultural heritage? How are you working with these tensions?

LD: We must keep a close eye on this tension. It would be interesting to explore how the use of this technique can develop into an indigenous practice with new meanings. It is important to consider the historical use and expansion of this technique during the colonial era and how it can be viewed in the present and future. We should also examine the medium of photography itself, which has been widely used for campaigns of domination and colonisation globally. How does photography carry on this undeniable historical baggage? As an artist and an archivist, I will continue to explore this question and interrogate if my perspective, like that of many other artists, can introduce new uses of this medium.

NH: During our research, we noticed a Somali Xirsi worn by a young female member of the troupe (figure 8). Accounts in the troupe’s deportation case file describe how jewellery belonging to female troupe members was vulnerable to confiscation by U.S. immigration officials. I wanted to return to this scene, to speak to Afterall’s Hiding in Plain Sight series. The scholar Simone Browne, draws attention to the modalities between darkness and shadows, and their potential as grounds for ‘speculation, contestation, and possibility.’ This feels like a useful framework for positing questions about the Xirsi, about the limits of provenance methods to trace confiscated jewellery. The photograph in question was taken in a police station in Chicago in 1915, when members of the troupe were arrested. In your cyanotype series, ‘Ilaalin; Waan Ku Ilaalin Doona’ (2023) (figure 3) opacity seems to be present.

Perhaps we can speak about the symbol of the Xirsi across temporalities here? Reading along the borders of these two images, there is both a historical continuity and an introduction of what Tina Campt describes as a “counter-image”. Observing a child, who is unable to consent to participating within the colonial economy of performing exhibitions wearing an amulet of protection raised tensions for us. The child could not be protected in the material sense, but rather spiritually. Why is opacity an important theme in your “counter-image” of the Xirsi?

LD: I am convinced that the Xirsi in this process for us, for those who come into contact with our project and will have the opportunity to experience it through their own eyes and ears, implements a real form of memory protection. For me, the Xirsi activates spiritual memory practices as an engagement with the concept of Descansos,04 a Spanish word that means ‘resting places’ as described by Clarissa Pinkola Estés in Women Who Run With The Wolves (2012). Through the Xirsi, we can put to rest and bring peace to the people in the images, especially the young girl who wears it in the photograph. The Xirsi’s value was once overlooked, but as time passes, its significance is recognized. Our project’s close cultural ties to Somalia, combined with the Xirsi’s growing popularity, make it an important object to explore in our project.

NH: In our investigation of the troupe’s state deportation case file, we were confronted by accounts of jewellery confiscations, performed by US officials05 who figured that the jewellery the female troupe members adorned themselves with held economic value. On August 25, 1915, a letter details how initial confiscations made troupe members begin to “ship their gold to their native land”. I proposed a provenance-focused intervention around these letters, but there is a limitation here. Robin Gray’s concept of rematration is a helpful starting point for extending the limits of provenance methods. ‘Ilaalin; Waan Ku Ilaalin Doona’ (2023) seems like an attempt to call back intimate knowledges rooted in Somali women’s material cultural expressions.

In Dark Archives (2015) Erica Scourti offers a way of thinking about ‘dark matter’ within archives, namely, information in an archive that cannot be seen. The items of jewellery confiscated by Chicago immigration officials might have been discarded, sold into auction, or ended up in a museum or private collection. The deportation case files acted as ‘dark’ archives we inhabited to trace the troupe’s trajectory in the U.S., despite the tensions involved.

Staying with the dark, I recently encountered a substantial digital photography collection of Somali ethnographic performers documented by Prince Roland Bonaparte at various international exhibitions of the late nineteenth century.06 The photographs are only accessible within the Quai Branly Museum’s digital collections as negatives. I do not imagine an ethical ‘veiling’ was the intent here, yet this made me contemplate our ongoing conversation on the act of ‘veiling’ colonial photographs. The reader may notice clear intentions with our image selections, for instance.

LD: The role of (the?) Xirsi in this story is fundamental, although it is deliberately obscured despite its image marking its presence. It is important to give voice to its need for protection, which acquires additional value in resisting to this day. Even though it lives hidden in the shadows, it highlights several aspects that become fundamental. I want to stress here that for a long time, these photographs were circulated within the Somali community with false representations. The troupe members were presented in some cases as Somali refugees who were welcomed in the U.S. This troubled us as we know that they were detained in Chicago after countless protests and requests for repatriation. This backstory highlights the opaque nature of this ‘dark archive’ deliberately kept hidden. This is where the work we are doing in Transmigrating Cassettes comes into play.

Through the process of reappropriation, the veiled image created through a cyanotype process reveals an element of photography that did not exist before. During the development process, I was able to decide what to show and what not to show. The almost total absence of the faces of the people portrayed highlights precisely this aspect of the question. Our focus is on the reality of these photographs while considering who lives inside the images. Therefore, sometimes, especially in a context of violence and power, it is necessary to stretch a veil that plays as a means of protection, reconnecting once again with the symbolic meaning of Xirsi.

NH: I want to discuss our use of audiocassettes. To think through Hiding in Plain Sight, was there an intention of opacity or subversion here? As we were dealing with a very charged photographic collection, initiating a sonic transmutation of a photographic collection felt like a provocation against the act of witnessing. Why was that important for us?

LD: The use of cassettes has become an integral part of SITAAD’s research process. Although the medium is fragile, it holds a significant place in contemporary Somali culture, especially within the diaspora. Audio cassettes have been used for many years to communicate over long distances, allowing friends, relatives, and acquaintances to have expansive conversations. This is similar to audio messages we send today. Cassettes also played a major role in housing the ‘golden age’ of music in Somalia. By using this medium to access and analyse this photographic collection from various archives, we were able to return a sense of familiarity to the Somali community. This medium evokes a sense of home, security, and trust.

NH: The cassette is a recognisable and familiar technology. We made an intention to only permit community-led circulations of the tapes, rather than via institutions. Retrospectively, I am wondering if there is a life for the cassettes in an ethnographic museum. Perhaps there is a potential in organising ‘listening sessions’ in these locations, and leaving with the tapes?

LD: I hope that these tapes can have a long and generational impact, with the Somali community but also further afield. Ideally, they will continue to disseminate this troupe’s story and its importance on their own. Listening to these tapes will hopefully create environments for generational discussion, where different perspectivescan be put on the table. These tapes should expand to unfamiliar sites, households and spaces of dialogue as part of a migrational path, as the name of our project suggests. As you mentioned, our relationship with institutions is critical, we emphasise the need for public education around colonial contexts. However, it is also important to remember that these tapes do not have a fixed home, particularly not in an institution where our history has been deliberately buried for far too long.

NH: Is there anything else you want to say?

LD: This practice we are forming is Xirsi itself. This is why the cassette publication includes a Xirsi. I would like the listeners to be protected. To voice this out loud, I hope to see the tapes circulate from one person to the next.

NH: Perhaps a new question with its own set of tensions is forming here: who will receive the tapes, the cyanotype prints of the troupe and what counter-institutional circulations are possible?

Further reading

Akou, H. M. (2006) Documenting the Origins of Somali Folk Dress: Evidence from the Bonaparte Collection. Dress. [Online] 33 (1), 7–19.

Atkins, A. (1843). Photographs of British algae: Cyanotype impressions.

Campt, T. (2017) Listening to images. Durham: Duke University Press.

Igwe, O. & Stokely, J. (2019) Hiraeth, or queering time in archives otherwise. Alphaville. [Online] (16), 9–23.

Harney, S. & Moten, F. (2013) The undercommons : fugitive planning & black study. Wivenhoe ; Minor Compositions.

Lavédrine, B. and Gandolfo, J.P., 2009. Photographs of the Past: Process and Preservation. Getty Publications.

Hoyt, S., 2022. Afro-sonic Mapping. Tracing Aural Histories Via Sonic Transmigrations. Archive Books.

Takács, Louis. “Let Me Get There: Visualizing Immigrants, Transnational Migrations and U.S. Citizens Abroad, 1904–1925,” [Online]. Alliance for Networking Visual Culture.

Tirak, L. M. (2021) Black and Blue: Revelations in Harold Mahoney’s X-rayed Anatomical Sections. The Rijksmuseum bulletin. 69 (1), 26–49.

PhD, C.P.E., 1995. Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype. Ballantine Books.

Warsame, B., 2021. Spectacles in. Staged Otherness: Ethnic Shows in Central and Eastern Europe, 1850–1939, p.77.

Footnotes

-

Transmigrating Cassettes is a sonic container for SITAAD research interventions on dispersed colonial collections which instrumentalises the audio cassette as an archival and discursive tool. In partnership with Soomaal House of Art and the Immigration History Research Center Archives, SITAAD initiated public programme themed around Vol.1 Transmigrating Cassettes in Minneapolis and New York City between August – September 2023.

-

A cyanotype is a cameraless printing formulation that involves laying a photographic print on a piece of plain (uncoated) paper, on which the image is composed of a blue pigment. The paper is sensitised with ferric (iron) salts. A yellow-brown image prints out during the exposure to the light. During the subsequent washing and drying, the image intensifies and is converted to a prussian blue pigment. See Lavédrine 2009.

-

In 1843, botanist Anna Atkins (1799-1871) published Photographs of British algae: Cyanotype impressions, which was illustrated with a collection of cyanotype prints.

-

“Descansos, resting places. You’ll also find them on the edges of cliffs along particularly scenic but dangerous roads in Greece, Italy, and other Mediterranean countries. Sometimes crosses are clustered in twos or threes or fives. People’s names are inscribed upon them, sometimes the names are spelled out in nails, sometimes they’re painted on the wood or carved into it […] To make descansos means taking a look at your life and marking where the small deaths, las muertes, chiquitas, and the big deaths, las muertes grandotas, have taken place. […] I encourage you to make descansos, to sit down with a time-line of your life and say “Where are the places that must be remembered and blessed?” – Clarissa Pinkola Estés.

-

The National Archives and Records Administration: Barnum & Bailey 53939-36b case files cover various issues concerning the troupe’s activities in the United States, including labour agreements with Barnum & Bailey contractors and legal correspondences, and later their deportations, arrests and their stays in detainee centres. The files also include several correspondences between government officials and Barnum Bailey contractors, along with testimonies. A finding aid was created to support the Transmigrating Cassettes Public Programme in Minneapolis, held at the University of Minnesota and Soomaal House. SITAAD worked with archive intern Hodan Hassan to produce finding aid.

-

See IX Somalis [Portrait of a seated man, bust, with the body in three-quarter view and the head in profile] Prince Roland Bonaparte (1858 – 1924), Gelatin-silver bromide negative on glass plate. Quai Branly Museum Digital Collection.