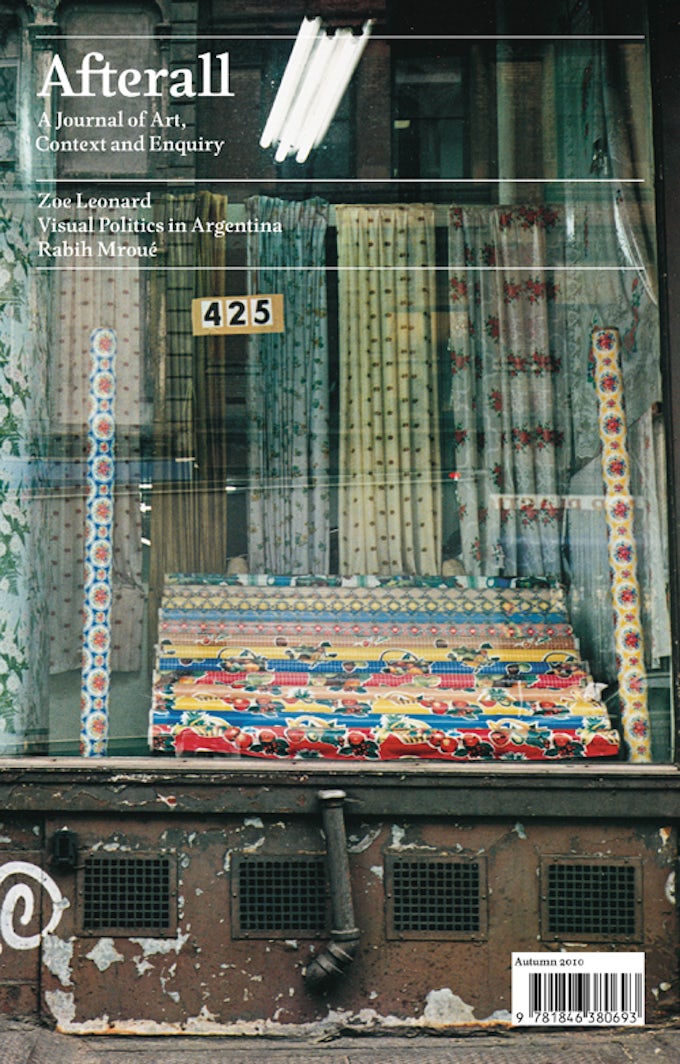

Issue 25

Autumn/Winter 2010

Issue 25 features essays on Zoe Leonard, Želimir Žilnik, Rabih Mroué and Judith Hopf. Accompanying essays look at the performance and poetry of Karl Holmqvist, responsive curatorial practice since the 1990s and visual politics under the Argentinean dictatorship.

Editors: Pablo Lafuente, Nuria Enguita Mayo, Dieter Roelstraete, Melissa Gronlund, Stephanie Smith.

Founding editors: Charles Esche, Mark Lewis.

Table of contents

Foreword

Contextual Essays

- Photographs and Silhouettes: Visual Politics in Argentina – Ana Longoni

- Another Criterion… or, What Is the Attitude of a Work in the Relations of Production of Its Time? – Marion van Osten

Artists

Zoe Leonard

- The Archivist of Urban Waste: Zoe Leonard, Photographer as Rag-Picker – Tom McDonough

- Goats, Lamb, Veal, Breast: Strategies of Organisation in Zoe Leonard’s Analogue – Sophie Berrebi

Želimir Žilnik

- Shoot It Black! An Introduction to Želimir Žilnik – Boris Buden

Želimir Žilnik

- Concrete Analysis of Concrete Situations: Marxist Education According to Želimir Žilnik – Branislav Dimitrijevi?

Rabih Mroué

- The Body on Stage and Screen – Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

- Conciliations: Witness and Spectator – Juan A. Gaitán

- The Fabrication of Truth

Judith Hopf

- Vita passiva, or Shards Bring Love: On the Work of Judith Hopf – Sabeth Buchmann

- On Entering the Room – Tanja Widmann

Events, Works, Exhibitions

- Karl Holmqvist: Making Space

Foreword

Written by Pablo Lafuente

The notion of authenticity doesn’t have much critical currency today, neither in art nor in politics. It is true that claims to authenticity are often made in relation to artists’ work, in discussions of citizenship and nationality and in connection with ethical issues in general. Such claims are one of the basic mechanisms through which the art system creates and maintains its value, and they further fuel institutional arguments and sometimes policies. But, associated with essentialist positions and dogmatic approaches, with closing

down critique rather than opening up to it, authenticity doesn’t appear the argument of choice when defending artistic or political practices that prioritise equality, critique, enquiry or change.

This wasn’t always the case. While Theodor Adorno dismissed the jargon of authenticity in 1964 – in existentialism in general and Martin Heidegger’s writing in particular – as complicit with fascism, before this rejection, and before the use of authenticity by Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus and earlier Søren Kierkegaard, the concept was discussed by Montesquieu and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. And just a few years after Adorno’s dismissal, Marshall Berman tried to bring back that discussion, and through it to recuperate what he identified as a key emancipatory tool. Berman traced in his book The Politics of Authenticity: Radical Individualism and the Emergence of Modern Society (1970) the emergence of the notion of authenticity in the work of those two early thinkers of the new, modern world, through the basic thesis that the search for

authenticity is, in modern times, ‘bound up with a radical rejection of things as they are’, that ‘the social and political structures men live in are keeping the self stifled, chained down, locked up’. The notion of the authentic in relation to the self, Berman writes, serves as a trigger for a critique of a status quo that is systematically unequal and for an impulse to disrupt, change or transform unjust social structures. Seen in this way, authenticity is arguably at the origin of every ideological construction that has proposed reform or

revolution and, on this basis, at the core of the history of political emancipation for the last 300 years.

Authenticity, as Berman finds it in Montesquieu and Rousseau, is a response to the new climate of modernity – a climate that ‘threatens the tree of man with mutilation or destruction’ but that at the same time ‘holds out a promise of unprecedented fruitfulness’. This response is not a rejection of the modern in favour of a pre-modern human nature, but an embrace of the complexities of modernity that cannot but reflect them through a series of tensions and contradictions. A few years later Berman offered a detailed and captivating book-length elaboration on how this modernity is experienced, in All That Is Solid Melts into Air (1982):

to be modern … is to experience personal and social life as a maelstrom, to find one’s world and oneself in perpetual disintegration and renewal, trouble and anguish, ambiguity and contradiction: to be part of a universe in which all that is solid melts into air.

The ‘melting’ of the title is then the result of a dynamic process of creation and destruction within which the individual can never find a stable position. In the face of this situation – and if we conflate Berman’s two books – to be modern is to be authentic, where this means being able to change and also to resist, to embrace and take advantage of the creative force of modernity and to fight against being annihilated by it.

Purchase

The publication is available for purchase. If you would like specific articles only, it is also available individually and to be downloaded as PDFs.

Purchase full publication

Buy via University of Chicago Press

Buy via Central Books

Purchase individual articles

Buy via University of Chicago Press