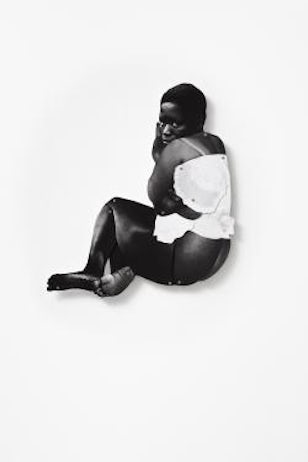

Facing the bleak display of Frida Orupabo’s high-contrast collaged bodies, pinioned against the grandiose, stark-white walls of the Kunstnernes Hus, I felt disturbed. 01 In one work, a young black family of three is smartly assembled in suit, fur coat and luxurious baby clothes, but they lie with their eyes closed, dead in the vitrine. The besuited mother has a noose around her neck. Dissected and hinged with brass split-pins, the larger collages recall flat paper dolls and, moreover, crucified specimens – forensic studies in abused, dehumanising poses, buttocks and legs exposed. In Orupabo’s Bellmeresque composites, bodies are disassembled and reconfigured – a stomach is swapped for a backside, a male torso appears in place of breasts – impossibly visualising Hortense Spillers’s conception of the oppressive ‘ungendering’ of black women’s bodies. 02 The figures’ dull staring eyes, directed at the colonial photographers, and now us, are the only sign of undead life.

Arthur Jafa, who Orupabo invited to collaborate on this exhibition, has spoken of his desire for a visual art which approaches the alienation of black music, a statement that suggests an affinity between their two practices. Jafa describes in an accompanying text Orupabo’s Instagram virtuosity – having encountered her work on social media, Jafa had previously invited Orupabo to participate in his 2017 exhibition at London’s Serpentine Gallery. Orupabo, compared to most people’s pedestrian use of the platform, ‘dances across it’ – Jafa prompts us to ‘check the thread to see how she’s moving us, forward.’ 03Like the most compelling examples of artists’ feeds on Instagram, Orupabo (‘@nemiepeba’) doesn’t submit to the disposability of social media image circulation and offers little usable data for her corporate hosts. She posts irregularly and, far from one-off instants, tends to share up to five images and short video clips at a time from her unflinching research practice; for instance, a post from September last year shows footage taken in 1914 of a Norwegian human zoo. Casually swiping through her account feels inappropriate, as a friend pointed out to me – literally pushing these uncomfortable images out of sight. At the same time, Orupabo’s use of Instagram reveals its unexpected efficiency in gathering an audience around such images, and its facility as an instant archive to keep returning to. The imagery is consistently black and white, as if restarting the history of cinema from an anti-colonial perspective, or in Jafa’s words, manifesting a ‘limbic expressway to our newly mediated black sociality’. 04

Before showing her work with Jafa at the Serpentine two years ago Orupabo was unknown to the international art world. And now she’s showing at Venice. Even though you’d hope more artists were discovered this way these days, this has often become the pretext to seeing the work, as if daring her to sink or swim against the industry’s relentless tide of consumption. In a rare interview with the Norwegian press Orupabo explains her approach as being primarily for herself, and then for those who see the artistic value in her work. ‘In the beginning, I wanted nothing but a kind of diary. A dialogue with myself. A place for my frustration, in terms of ethnicity, complexion, sexuality, gender. I work with pictures I can recognise myself in. They rarely saw me when I grew up.’ 05

During my visit I could feel different types of value at work, for different audiences. The gallery interpretation is largely left to Jafa to explain: why Orupabo, why now? I left the gallery reeling from the rawness of the work and the lack of vocabulary to speak about it, triggered by what I felt were relentless images of colonial violence. The degradation in the women’s appearance seemed continuous with the racialisation, and dehumanisation therein, of black and brown bodies. It felt like an exercise in fulfilling expectations – exonerating or at worst titillating the white supremacist gaze through exposing the trauma of black pain in the historic figures of the mammy and slave mother. Similarly, Jafa’s contribution to the show, Love is the message, the message is Death (2016), is a fast-paced 7-minute video montage showing scene after scene of white-on-black violence and murder in the United States, interspersed with milder and at times joyful moments from home videos and cameos by black musicians and writers, and overlaid with the looping refrain of Kayne West’s euphoric track ‘Ultralight Beam’. The work seemed to use every cinematic device in the book to spectacularise black pain.

Jafa has stated that he feels numb to the witness videos; yet the experience of seeing them in a predominantly white gallery context reinforces the fact this trauma is felt more acutely by (most) black and non-white bodies – the imposing architecture at Kunstnernes Hus only echoes this. Jafa has expressed ambivalence about Love is the message… being shown in gallery spaces – he refused to show it at the Serpentine, preferring that the video should tour nomadically around housing estates ‘at the edge of town’ (though this plan was never realised). 06 And when I did unexpectedly find the offsite location on top of London’s Vinyl Factory, in this relatively informal context strewn with beanbags, I remember enjoying the sensual, even jubilant parts of it more. In that setting, it didn’t seem so overwhelmingly dark. Recent artists’ approaches to similar source material have been varied: Tony Cokes, for instance, replaces violent scenes with text, in part as a strategy against desensitisation to anti-black violence. Such an approach is perhaps more effective in offering a bridge between audiences, in contrast to the alienation effect favoured by Jafa, and corresponds with Walter Mignolo’s call for a decolonial aesthetics that turns away from matters of representation – committing instead to exposing the contradictions of colonialism and its ideals of Western beauty and taste. 07 In a connected way, certain works by Orupabo – found photographs showing examples of black healthcare, talismanic insignia and fierce weaponised hybrid figures – conjure a defiant route out of the normativity that black bodies are inscribed within.

Leaving the gallery I began to understand that the exhibition was at cross-purposes, slipping between the intentions of each of the artists and caught between sites and mediums, distorting the effect of the works. Although the entirety of Orupabo’s exhibition could be packed in a single portfolio or archived on Instagram I did feel that, especially through her unframed works, she was insisting on the materiality of the situation in Oslo: finally making an exhibition in her home country, where she grew up taunted by racism as an anomalous child of mixed heritage in a small farming village, and in the city where she now works as a social worker helping victims of trafficking and sex workers, many of Nigerian heritage similar to her own. I understood this lived reality, in contrast with the affluence of the gallery only twenty minute’s walk away from the docks where prostitutes work at night, as the bleak situation Orupabo wanted to address. The macho bombast of Jafa and Kayne’s video at the other end of the gallery felt like a red herring, only enhancing the discomfort of being surrounded by so many images of maternal-yet-necropolitical figures, with exhausted-yet-doting eyes and desires that aren’t their own. 08

But the most disturbing aspect of ‘Medicine for a Nightmare’, perhaps, lay in something beyond the works themselves. I was acutely conscious of the different ways these works may circulate in the artworld’s white spaces, and of the violences and distortions that this transfer produces – particularly for those living at the receiving end of racialised and sexualised violence. At Kunstnernes Hus, perhaps inevitably, Orupabo’s broader social practice and intellectual research remained outside the frame. If these are the necessary exclusions of a white-cube show, they nonetheless frame the artist as an exception rather than an agent of deeper and more revealing truths. And here, Instagram appears to pick up the slack left by institutional inertia. Orupabo’s online posts feel much more timely and vibrant; her captions (also absent in the exhibition) offer valuable context and information; open comments allow other modes of response or interpretation; and her hat-tips to fellow internet archivists, artists and film-makers engaged in social justice research offer direct routes to a wider audience and network. While the presence of artists such as Jafa and Orupabo is of course crucial in major institutional spaces – for the long project of undoing established canons and their modernist-colonial, conservative and commercial logics – these spaces have everything to lose if new and non-traditional audiences don’t find them relevant or, as is the risk I felt here, they are further alienated by attending them.

Footnotes

-

‘Frida Orupabo and Arthur Jafa – Medicine for a Nightmare’, Kunstnernes Hus, Oslo, 1 March–21 April 2019.

-

See Hortense J. Spillers, ‘Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book’, in Diacritics,vol.17, no.2, Summer 1987, pp.64–81.

-

‘Frida Orupabo and Arthur Jafa – Medicine for a Nightmare’, Kunstnernes Hus exhibition pamphlet.

-

Ibid.

-

‘As Brilliant as the Sun’, Arthur Jafa interviewed by Jace Clayton, Frieze, February 2018, https://frieze.com/article/brilliant-sun.

-

See Walter Mignolo and Michelle K., ‘Decolonial Aesthesis: From Singapore, To Cambridge, To Duke University’, in Social Text Online, 15 July 2013, available at https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/decolonial-aesthesis-from-singapore-to-cambridge-to-duke-university/.

-

Hortense Spillers argues that the absent father in African-American history is the white slave master, since legally the child followed the condition of the mother (via legal doctrine partus sequitur ventrem). Therefore the enslaved mother was always positioned as a father, as the one from whom children inherited their names and social status. See H. J. Spillers, ‘Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe’, op. cit.