Since the 1960s, Joan Jonas has pioneered the use of performance in film and video through a physical engagement with commonplace materials, bodily gestures and technologies. Having initially studied sculpture before ‘stepping into the space of performance’, Jonas intuitively manipulates rudimentary materials, from paper cones to mirrors, masks, folding fans and blackboards, thus amplifying their symbolic potential. It is a visual vocabulary born out of an almost ‘surrealist proclivity for startling juxtapositions’,01which Jonas compares to transformative modes of literature, explaining, ‘I think of the work in terms of imagist poetry; disparate elements juxtaposed… alchemy.’

This deeply personal visual language is in constant transformation, as is her ever-evolving and self-reflexive practice. Individual works – whether originally created in video, performance or installation – exist in transit, they are mutable entities translated and restaged into other mediums in later life. As such, Jonas’s practice produces a uniquely circular trajectory, acquiring an uncanny ouroboros quality by simultaneously expanding and folding back on itself over time.

In March this year Jonas was at Tate Modern in London to stage Draw Without Looking (2013) her first online performance. In the conversation below, Amy Budd speaks to Jonas about performing for an online audience, navigating her vast personal archive and her enduring fascination with literary canons.

AMY BUDD: Your performance at Tate was the first work you have specifically made for an online audience. When devising the work, how did you prepare for this particular medium, knowing that the audience would be experiencing it through a computer screen, rather than on monitors, or as an installation?

JOAN JONAS: I have always performed and made images for the camera or a live audience. I began with the mirrors as props, and then I saw the monitor reflecting what the camera sees as an ongoing mirror. So I am used to working in relation to the camera – I can be in my own loft, performing for the camera while watching the monitor. So in that sense the structure was similar, the big difference was that there was a live audience out there behind the camera.

AB: Given that creating images is a primary focus of your work, did this change when you envisaged the performance being experienced through the intimate encounter a computer screen creates? Existing only inside the space of an incredibly contained, flat frame?

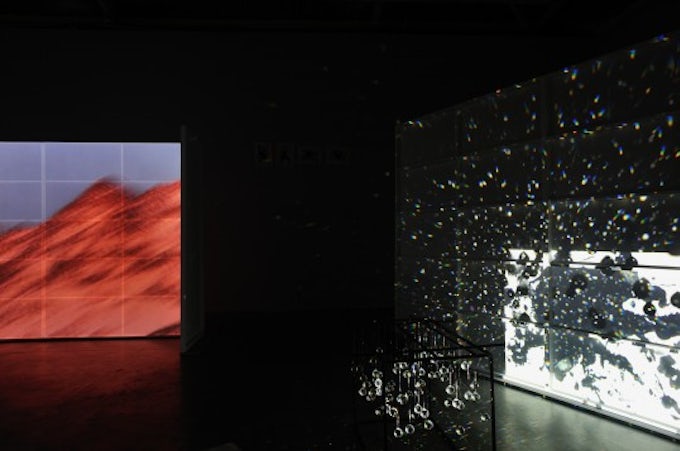

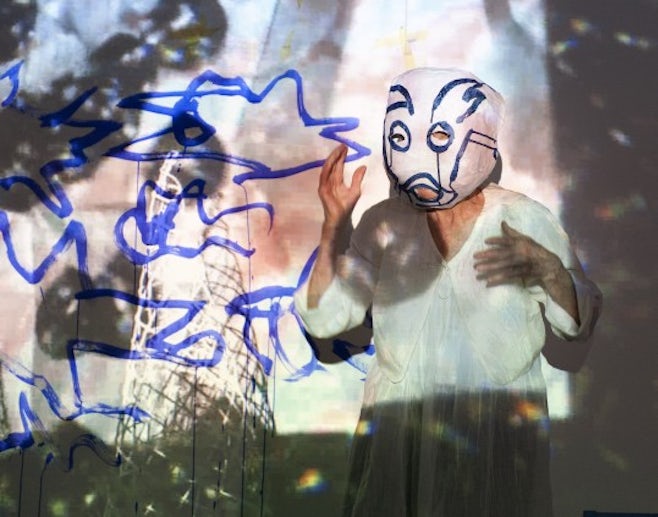

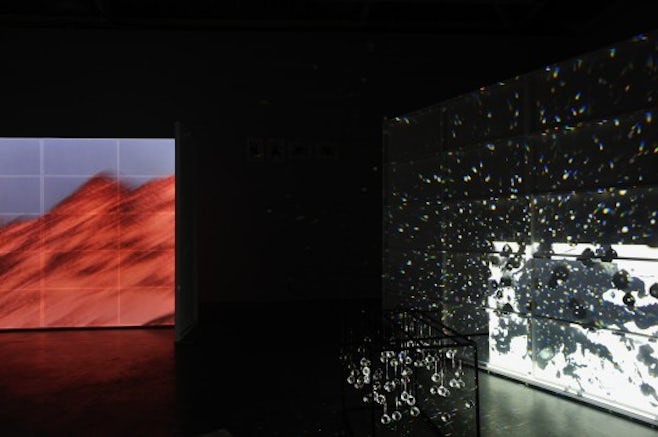

JJ: I have always thought of video as a flat medium, and so the difference between the monitor and the computer screen is not that big. For the Tate performance it was like I was creating a miniature because almost everyone would be viewing it on the small screen of a personal computer. I began by editing a video, working with unused footage of crystals that I shot last spring for my installation at dOCUMENTA(13), Reanimation (In a Meadow) (2010–12),02 and adding the re-edited soundtrack that I had made with Jason Moran for a performance version presented after the installation was finished. I made a space with this video, a projected space, which I then stepped into. To me it looked like a room. I always consider the space I am performing in. For instance, for the video Glass Puzzle (1973), I imagined the monitor as a box that I could climb into, constructing a stage set with paper especially for that framed space, which the performers moved into and out of. At the Tate, the video projection created an illusion of space that I performed in for the camera. I thought of the viewers peering into it.

AB: Your moving body appeared to activate the space, reaching and, in turn, revealing the corners of the room, which weren’t immediately obvious.

JJ: Yes, it was a new kind of space for me. While performing I watched myself on a monitor, in order to guide myself. I thought it was good to make direct contact, which is why I began the piece that way, speaking to the audience.

AB: Dressed in white, your body was almost entirely camouflaged by the materials of the projection. I wonder how you intended your body to be read in that visually oblique situation? Given your interest in Noh theatre, it also seemed reminiscent of Japanese Bunraku puppetry, where the puppeteers are dressed in black, so the audience focuses on the actions of the puppets, but not the performer.

JJ: The Bunraku is amazing theatre, but I wore white in order to interact with the projection, disappear and reappear. If I had worn black, you’d see the figure because the projected image would be absorbed by the black. I was interested in how the projection appeared on my body and the way I appeared in the work. I still have to absorb this and explore it further. Usually in my video performances the video sequences or backdrops rely on my timing: they follow me. In this case the video played and I responded, so there was a different dynamic. I wanted to be integral to the texture, to both blend in and stand out at different times. It interested me to be in the projection of the crystals.

AB: Do the crystals operate in the same way as mirrors in your work, as ritual objects?

JJ: In a way, yes. They fragment the space and reflect it. They are also transparent, you can see through them, or you think you can see through them sometimes. I like that illusion.

AB: In your inaugural lecture as Visiting Professor at the Royal College of Art, London earlier this year [5 March 2013], you spoke of your ongoing fascination with mirrors, particularly ‘how the mirror as a medium alters the space’. How does the mirror operate as medium in your work, rather than another prop or object?

JJ: It is another tool. From the very beginning I was interested in how I could alter the image. Of course it was a prop, but then it became a medium through the way I used it. In Mirror Pieces (1968–71), for example, there wasn’t just one mirror – there were seventeen mirrors held by seventeen performers. As the performers slowly moved the mirrors, the mirrors altered the space and the image of the space. The audience saw themselves, each other, and the performers in the mirrors. When I began to work with video I saw it as an ongoing mirror. I worked with a closed circuit system of a video camera and monitor in relation to the live subject, to explore the way the subject would be altered as it passed through this system. The medium transformed the experience of the actual live subject through the mediated video image. The mediated image transforms what we think of reality.

I immerse myself in these various mediums. At the same time as I began to work in video, I was experimenting in performance with distance and landscape. In works such as Jones Beach Piece (1970) and Delay Delay (1972), distance became a medium that altered the audience’s perception of movement, object and sound – the audience was situated a quarter of a mile away from the performance.03The film Song Delay (1973) is based on these performances. The crystals in Reanimation (In a Meadow) also create a kind of medium.

AB: It’s interesting that you mentioned Glass Puzzle before as this was made in the isolation of your studio, whereas Draw Without Looking was produced in a larger and more public space – the gallery. Did you have Glass Puzzle in mind as you were planning this new work?

JJ: Glass Puzzle was a video I made in my loft. We constructed spaces with black and white paper, but actually almost my entire loft was the set. There were two performers [Jonas and Lois Lane] and all the moves were in relation to the real space or the space of the monitor, and related to the poses of women in photographs taken by the photographer E. J. Bellocq who photographed prostitutes in New Orleans at the turn of the last century. Usually I shoot my own works, but in this case the cameraperson, Babette Mangolte, was really a collaborator. The gallery in which I performed Draw Without Looking was actually a smaller space than that loft. I often think of the set for Glass Puzzle as a kind of template.

AB: Could you say more about producing work to be viewed online? When I watched the live-stream performance, at times the image became quite pixelated, probably because my broadband wasn’t fast enough. I wonder how you respond to this, when the transmission affects the quality of the images you’re so carefully creating?

JJ: You know, for me it is the only drawback of working in this medium. If you work with video and put it out in the world, you don’t have control over how people are looking at it. Even in a museum there may be the wrong kind of projection, or maybe an old projector whose bulb is burning out or the colour is wrong. I looked at the recording of the performance on my iPhone and that was horrifying, in a way. But I am willing to let it go, you have to let go. People’s experiences will simply be different in different situations.

AB: As Draw Without Looking demonstrated, you’re continually recycling props or restaging gestures in your videos and performances. And so by returning to past works, materials and ideas you create a vocabulary that is constantly renewing and reflecting itself. I wonder how you navigate your archive. How do you choose what to re-present and re-perform?

In the sixties, there was a reaction against literary sources but I wanted to develop my own particular aesthetic. Borges was an early inspiration – reading his short stories, I was interested in the way he wrote about mirrors.

JJ: It is based on how I feel about a past work. One of the works that I have revisited isMirage (1976), partly because the material has an abstraction that can be reconfigured. It began as a video performance in 1976, which used just 5 minutes of a 30-minute film made by myself and shot by Babette Mangolte. I then edited this entire film together with another sequence of footage shot at the same time and it became another work, which was included in the various installation versions of Mirage in the 1990s. Finally when the Museum of Modern Art in New York bought the installation, I decided to leave it. For my most recent work, Reanimation (In a Meadow) (2010-12), I used footage from a video made in a swimming pool called Disturbances (1973). Reanimation, is partly about glaciers that are now melting and the image of the surface of the pool with people swimming in it seemed perfectly appropriate. Likewise characters reappear; I used the figure of Melancholia in various works, such as The Shape, The Scent, The Feel of Things (2005–06) and in Reanimation, because of its multiple implications.

AB: Your work also draws on a wide range of literary references, taking on canonical figures from Dante to Borges, or the modernist poetry of Yeats, Pound and H.D. [Hilda Doolittle], using literature to find your voice. What has attracted you to these particular writers and texts?

JJ: In the sixties, there was a reaction against literary sources but I wanted to develop my own particular aesthetic. Borges was an early inspiration – reading his short stories, I was interested in the way he wrote about mirrors. Literature has always been a source for my work, but while I write and edit fragmented texts, I don’t consider myself a writer but a visual artist.

AB: Is there a danger of suggesting a hierarchy between performance and video, through your translation of one into the other? Ultimately video has a certain amount of longevity that undocumented performance doesn’t.

JJ: No I do not see a hierarchy. I constantly go back and forth between performance and video. For instance, if I work on a performance and it becomes an installation, I re-edit the video and find other ways to deal with the material. Then, when I repeat the performance, I might reintegrate this new edit into the performance. From the very beginning I was interested in making films and videos and in translating the live work into these mediums that become autonomous works themselves. However, these new edits are also altered as they are integrated into the live work. For instance, as I re-install or re-performReanimation I might very well integrate the material I’ve developed for the Tate.

AB: It’s an incredibly fluid, self-reflexive way to work insofar as you are not creating individual works as such, but rather a whole vocabulary that is produced and refined over time.

JJ: That’s right, I always thought of my work as being a kind of language. So over the years, I have always thought of building up a language of my own, a visual language.

AB: How would you characterise this?

JJ: Well, it is hard to say. It is the way I thought of the structure of poetry, the way that early imagist poets such as, Pound, H.D. and William Carlos Williams put images together to make another image, and also of the structure of the Japanese Haiku. I have always worked that way.

AB: Your work at times acquires a strange ahistorical quality, perhaps due to the way you combine new technologies with archaic references to other cultures. When watching Wind (1968), your first video work, I couldn’t place it. It felt reminiscent of early modernist film.

JJ: I was very influenced by early Russian, German and French film-makers. I have always been interested in how rituals began in different cultures. The Noh theatre started as a ritual and I wanted to think about the rituals of my own context, what it meant to be making performances for my friends in these downtown spaces in the sixties. In the past I have quoted some of the rituals of other cultures in my work, for instance drawing in the sand.

AB: And these rituals enable a practice that both produces and destroys images and materials – you wipe away your blackboard drawings, and also crumple up the paper in Reading Dante. You are not precious with the materials and rituals you draw from.

JJ: No, the material is meant to be manipulated and changed to create certain effects, to draw on. Paper is very sculptural, perhaps more stable than video. In performing a drawing, it is not about making a precious object, it is about the action and the image. It gives me pleasure to crumple the paper, to create another fleeting moment like the performance itself.

Footnotes

-

Susan Morgan, Joan Jonas: I Want to Live in the Country (And Other Romances), London: Afterall Books, 2006. p. 20.

-

Based on the novel Under the Glacier by Halldór Laxness, with Jonas utilising glass, crystals and diffracted light to symbolise ice, Reanimation (In a Meadow) (2010–12) was installed in a remodeled pre-fab house in Karlsaue Park, Kassel during dOCUMENTA(13) in 2012. Later versions such as Jonas’s recent installation at Yvon Lambert in Paris were titled simply Reanimation (2010–12).

-

Jones Beach Piece is one of Jonas’s early Outdoor Performances (1970–90), originally staged on Jones Beach, Long Island. Here, Jonas played with de-synchronisation, performing for a viewing audience situated a quarter of a mile away. Jonas continued to manipulate these delays in her subsequent performance, Delay Delay (1972) and film, Song Delay (1973).