While art-world interest in Third World cultures waxes and wanes with each decade, the 1980s version is marked by heightened awareness of the fact that the way artwork from the realm of ‘the Other’ is presented shapes our perception of it. The endless discussion about the relation between so-called marginal cultures and the mainstream has forced more than a few critics, curators and arts administrators to scratch their heads and think before designating a cultural product as folklore, as artifact or as ‘derivative’ of Euro-American modernism. And while the usual arbiters of taste continue to refine their terms, the most interesting art coming from the ‘marginal’ spheres continues radically to redefine them.

I am sure that more than one sympathetic visitor to the third Havana Biennial of Third World art dreamed of finding a way through some of these thorny issues in a locale far from the dastardly capitals of cultural imperialism. Too bad there were few answers to be found. The main exhibition’s conceptual weaknesses were too apparent to be masked by the sense of internationalist solidarity that inspired the venture in the first place. Though the organisers decided this time to rid themselves of the headaches and political maneuvering brought on by competitions and prizes, they trapped themselves with a hackneyed theme – ‘Tradition and Contemporaneity’ – and couldn’t find a way to revitalise it. The selection of works for the main exhibitions was void of impressive, powerful pieces such as the provocative installations of the younger Cuban artists in the previous biennial. The absence of performance on the one hand, and the inclusion of black artists from Britain but not from the US or France on the other, were bizarre blunders.

Out of context and unbecomingly arranged, too much of the work looked as if it were designed for airports and embassies. Another substantial portion appeared to copy elements of indigenous and popular cultures with an unfortunate lack of grace. And countries such as Mexico and Brazil, with outstanding reputations for producing cutting-edge reinterpretations of popular traditions, were disappointingly represented.

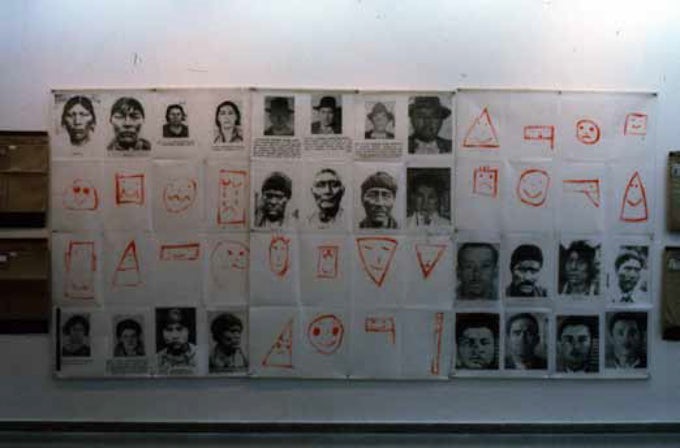

At least these curatorial flaws could not completely destroy the quality of the truly outstanding pieces in the main exhibition. Most of the strongest work utilised photography, among the youngest and least ‘traditional’ of Third World arts. The Chilean neo-Conceptualist Eugenio Dittborn’s Story of the Human Face [La historia del rostro, 1989] brings together anthropological and criminological photo-documentation and children’s sketches to create a striking reflection on the social and political implications of portraiture. Gerardo Suter of Mexico distills mythical bonds with precision and flair in his large-format photos of human figures with animal masks. At the other end of the technical spectrum were a variety of well-rendered faux-naïf paintings from West Africa with politically charged texts describing contemporary social ills.

The peripheral shows scattered around the city’s many galleries by far exceeded the main show’s capacities to reinterpret histories, cultural identities and conventions usually associated with the term tradition. Cuban artist José Bedia’s solo show of installations and drawings demonstrates this young, extraordinarily accomplished artist’s ability to rework the Afro-Cuban symbolism from Santeria and Abakuá and to explore the Cuban revolutionary concept of technology and development in light of these older forms of knowledge. Prize-winning Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide’s images of Juchitán (soon to be exhibited in San Francisco) take ethnographic traditions to a rarely achieved level of lyricism, while Brazilian photojournalist Sebastião Salgaldo’s spectacular documentation of labour in the Third World was enough to make one think about photography as political activism without the usual cynicism.

Until the explosive cultural atmosphere of the 1980s, committed art in the Cuban revolutionary context was by and large obliged to tow the party line. Over the last several years, the very hip and very sharp youngsters who keep pouring out of the country’s Higher Institute of Art have launched several pointed critiques of social and political ills and bureaucratic pretensions in the form of performances, graffiti and public art and parodic mixed-media installations. The biennial’s attempt to showcase some of these efforts is a sideshow called ‘The Tradition of Humour’, a title that seems intended to dilute the works’ impact. Nonetheless, the best of the artworks subvert sacred symbols and slogans and take an astutely critical look at the relations between art, the artist and the revolutionary state. Glexis Novoa’s luridly coloured installation, for example, converts social realist iconography into nonsensical ciphers, a blunt comment on that style’s fossilisation.

Pieces such as this clued many a visitor in on the current cultural climate in Cuba, where the rambunctious creative energies of the young generation have been subject to mounting control, in the wake of Castro’s public rejection of perestroika and the disastrous Ochoa affair. A show containing more than a few ironic images of Fidel was shut this autumn and brought about the downfall of the highly respected vice-minister of culture, Marcia Leiseca, for refusing to wield the axe. Shortly thereafter, another exhibition that dissected the commercialisation of art in Cuba and used the official portrait painter of the Communist Party as a symbol of the relation between the artist and the state was dismantled two days before the opening. The well-known and esteemed art critic Gerardo Mosquera, several of whose recent articles have been censored, claims nonetheless that the atmosphere is not one of total repression, but of open conflict and debate. Still, several of the artists who have been through round-table discussions in public and private were more sceptical. ‘The dialogues always end in monologue’, said one artist whose show had been censored. ‘They’re just sticking the thermometer out to check our temperature.’

-Coco Fusco

Editors’ Note: This text was originally published in The Village Voice, 9 January 1990, p.90.