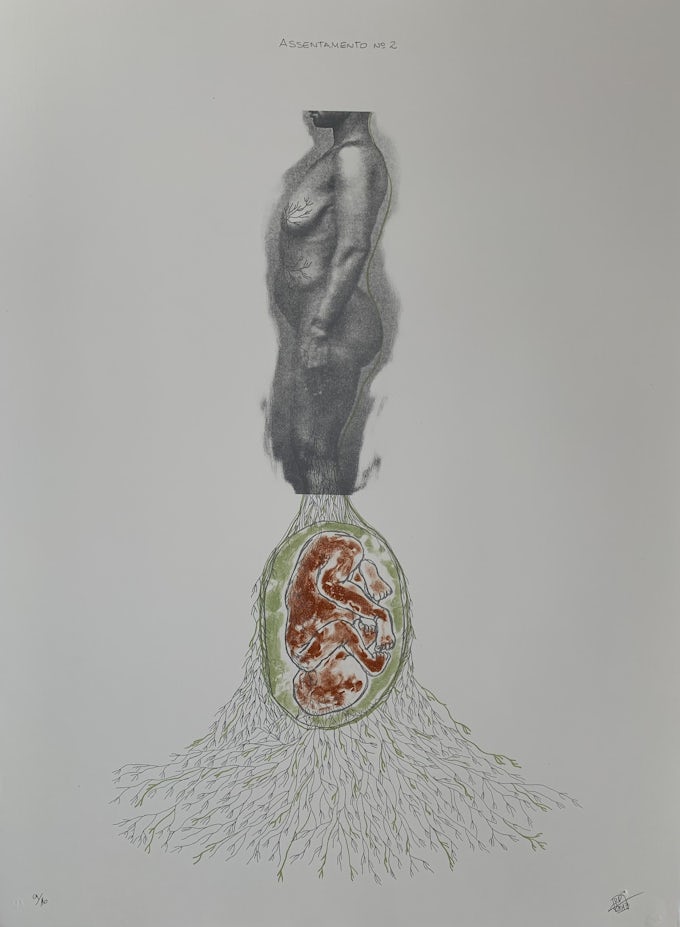

In one of a series of lithographs titled Assentamento, or Settlement, multimedia artist Rosana Paulino confronts the trauma of slavery for the unfree and their descendants. She ponders the disintegration of self and the violation of body that turned captives into property. As in much of her work, she pays homage to Black women’s labour of cognitive reorientation and their attempts to maintain bodily integrity in the context of psychic and physical suffering that threatened their very humanity. Paulino’s work addresses the importance of Black women in what Vincent Brown calls the political life of slavery, in which ancestrality, mourning, commemoration and regeneration were fundamental to the struggle to remake their condition.01 These efforts to remain recognisable to themselves as human, as Stephanie Smallwood asserts, required coherent narratives through which to understand this profoundly alienating physical and metaphysical experience.02 Paulino’s art contemplates the labour in which women engaged to create epistemologies and lifeways that fashioned these stories and connected the past with the present and the future in sustaining ways.

In the Assentamento series, Paulino imagines Black women as the seeds and roots of society and culture in Brazil; it is their suffering and their achievements that have ‘settled’ the land and birthed other universes that continue to oppose coloniality’s world order.03 This process of settlement and struggle plays out under a horizon of death that haunts her work. Genocide and terror built the nation-state and continue to characterise Black Brazilians’ relationship to it. The insistence in her work on the weight and persistence of slavery’s afterlife in contemporary Brazil have no real precedents in the country’s art scene. Paulino’s work over almost three decades historicises the ongoing negation of Black lives. It is a frontal attack on an official narrative that persists in telling stories of slavery with nostalgia, and as the felicitous foundation of Brazil’s mestiço civilisation. Her art and the ways of thinking and seeing that it proposes dismantle long-standing and powerful visual regimes that naturalise anti-Black violence.

Paulino’s spaces of settlement imagine new conceptual ground for thinking about the forms of oppression, as well as the forms of life and knowledge that emerged and persist under slavery’s past-present. The dominant spatial paradigm for understanding Brazilian civilisation – Gilberto Freyre’s Big House and slave quarters (Casa-grande e senzala, 1933, published in English translation as The Masters and the Slaves, 1956)04 – imprisons Black Brazilians and Black futurities within a frozen time-space. The notion of settlement pushes against the limits of that geography of confinement to disrupt the Big House/slave quarters binary. Like the plots or provision grounds that Sylvia Wynter identified as the locus of traditional African use-values related to the land (1971), settled spaces and the geohistorical knowledge they produce are fundamental to imagining life otherwise.

Paulino’s ‘settlement’ therefore offers us a critical vision of ‘plantation futures’, or decolonising thinking that is predicated on human life as well as on the socio-spatial workings of anti-Black violence and death.05 Building on her series of lithographs, Paulino’s 2013 installation Assentamento creates a wide field of signification for thinking Black geohistories. While the literal meaning of ‘assentamento’ is ‘settlement’, it has several other meanings. In Candomblé an assentamento is the ritual of turning the earth into sacred ground. It involves planting the collective energy of the community there, to create a space for which all are responsible, and which facilitates connection and communication with the orixás. ‘Assentamento’ is also the laying of a foundation; the layering of materials during construction; as well as a land occupation. Additionally, assentamento can refer to the act of recording or registering information, which I understand as forms of Black archival production. Given the protagonism of Brazilian women in Candomblé and in political spaces of Black mobilisation for land,06 I propose assentamento as a Black feminist theory and praxis of place and of documenting Black lives. I argue that assentamento is key to understanding Black life, death and sociocultural re-invention in the Americas.

Central to the Assentamento installation is the enslaved woman from the previous series. The complete work features three photographs of her (front, lateral and back) taken during the Thayer Expedition to Brazil led by Louis Agassiz in 1865–66, and now held at the Peabody Museum at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The expedition recorded somatological and phrenological characteristics of ‘pure racial types’ among African ethnic groups in mid-nineteenth-century Rio de Janeiro in support of Agassiz’s thesis on their inferiority.07

In this work Paulino sutures back together the body and its exposed, bleeding heart after its violation by the white supremacist gaze of the Harvard biologist. The bundles of kindling on either side of the figure, mixed in with clay replicas of human arms, evoke human labour, but also bodies that are easily combustible and extinguishable. The crates below them suggest goods traded and the fungibility of the female figure. Her displacement from a homeland occasions her loss of humanity and represents a wound that never heals despite the attempt to suture. The sutures themselves are very visible, and while they put the body back together, they do so imperfectly, distorting its original form.

The sutures speak to the meaning of ‘assentamento’ as a ‘record’ or ‘register’, by inscribing the hurt but also the humanity in the imperfect attempt to heal. This violated body confronts us as a proposed site of Black archival production and a different kind of foundation of knowledge. It recognises the distortions of enslaved women’s lives and bodies that are inherent in the archive that disfigures and fragments them. Their bodies and flesh become inscribed with the text/violence of slavery so that they emerge through what Marisa Fuentes calls a mutilated historicity.08 The labour of assentamento, of settlement, is the production of knowledge and systems of meaning that illuminate the violence of this historicity and provide a counter to epistemicide. Here physical violence against bodies is conjoined with the objectification and violence of the archive and of scientific knowledge. In order to lay foundations for ‘fugitive knowledge’,09 assentamento unpacks colonial constructions of race, gender and sexuality that continue to support power structures in the diaspora today. The installation includes sounds and images of the sea that speak to the amputated herstories of those forced to make the crossing and the many imagined returns. This constant movement, both physical and notional, of crossing, settling and resettling after displacement creates the basis for thinking about Black time-spaces.

Assentamento is how ‘no-bodies’, those not covered by the protections that citizenship affords and who inhabit conceptual and material ‘nowhere’ places,10 produce spaces that sustain their social reproduction despite the constant threat of annihilation. In Brazil, these fugitive geographies of settlement are produced, cognitively and physically, as the calunga and the quilombo. The calunga evokes the Atlantic crossing of captive bodies and the notion of the sea as cemetery: ‘Calunga Grande is the sea. Calunga Pequena is the tomb. Calunga Grande is the vastness of the saltwater, Calunga Pequena is the earth that receives those bodies and transforms them into seeds of a different life.’11 In Brazilian Umbanda belief systems, the calunga is the immensity both of the sea and of death; it is Black life lived under a ‘horizon of death’ as it engages in the difficult business of dreaming possible futures.12

As in Paulino’s installation, the calunga represents the meeting point between sea and land, geographic sites and imaginaries that are interdependent. In the way of Tiffany King’s ‘shoals’, which offer a perspective for thinking about Blackness beyond the analytics of water,13 the calunga connects land and water so that Blackness is not reducible to the Atlantic. Instead, Blackness in Brazil posits itself on that connection, and the conception of meeting points confers significant meaning to Black life, possibility and struggle. The grounds of Black settlement are in the calunga, where the sea is simultaneously the land as the site of a praxis of refusal. Both land and sea are therefore sites of assentamento, a moving, mutable archive of lives lost and lived in the diaspora. The calunga is a site imbued with spiritual, emotional and intellectual resources to address the violence of enduring arrangements of racialised power. It speaks to both the act and the place of crossing, in which the body, the sea and the land are part of a continuum of historical and ongoing movements that characterise fugitive Black geographies.

The quilombo emerges from the material and conceptual ground of the calunga, as part of what I call a cartography of insubordinate living produced by the process of assentamento. In developing this notion, I am inspired by the writer Conceição Evaristo. Evaristo understands the words she accumulated in her home and community as offering ‘a double movement of flight and insertion in the space in which I lived’.14 That ‘double movement’ produces insubordinate spaces of refusal that can be difficult to govern. Black women’s quilombola geographies emerge in those physical and notional spaces against, alongside and within those of colonial settlements and nation-states that have always disturbed the sleep of the Big House.15

Informed by Paulino’s work, I understand the ongoing process of settlement in Brazil as forms of dealing with the psychic pain and the physical violence of repeated dislocation over sea and land. I propose that assentamento, or a fugitive way of occupying space, grounds a sense of Black personhood and serves as a locus for articulating Black humanity. It is a way of pondering Black futurities that relies on movement, in the way that some practitioners of Candomblé understand knowledge as being constructed through movement.16 Assentamento is the struggle for a place to call home; it provides the individual and collective strength to denounce urbicide and environmental racism; it is an affective resource for dealing with dispossession and violence; it challenges epistemicide. Within the academy, it also resignifies ‘settlement’ beyond the frame of settler colonial studies to protagonise the agential possibilities of Black geographies.

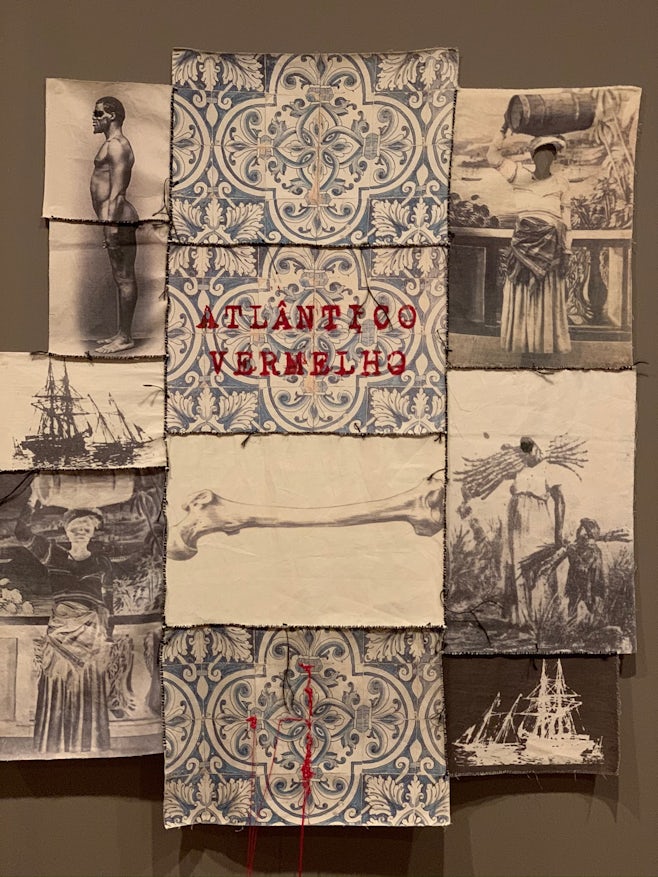

The sea as both the nightmare of dislocation and the dream of a return to the land is at the conceptual heart of Paulino’s Atlântico Vermelho (Red Atlantic). The map of the hemisphere that the slave trade made and the ways in which it configured society and culture across vast territories is a space produced in blood. Evoking the gendered labour of women quilting, she stitches together a vision of the calunga that evokes an ocean tinged with the blood of captives and that serves as a cemetery for their remains. The calunga measures the time and produces the space of Black suffering and death, but also of hope and rebirth. Somehow, as Paulino has observed, the enslaved ‘settled’ communities and cultures and generated resources from the spaces of the calunga and quilombo to meet the needs of their circumstances.17 Their death and their survival find an echo in this work.

The geometry of colonial classification that is suggested in the form and organisation of the panels is also disordered and disturbed in the work’s uneven shapes and conspicuous sutures. The Portuguese caravels on either side of the central panel mark the geohistoric moment of the implantation of colonial power and the transatlantic trading routes of objects and bodies. It also establishes coordinates for particular experiences and spaces of the calunga and quilombo: of suffering and refusal; of blindness and envisioning. The images of the enslaved taken from photographs and art of the period are digitally printed on the left and right panels, and all of the figures have been blinded. The photograph of the adult male at the top left also comes from Agassiz’s expedition. Like the photograph of the woman in Assentamento, the man’s body has been sundered by the violence of the scientific gaze and roughly sutured back together. In a further act of violence, his eyes have been scratched out. Also apparently violently deprived of sight is the enslaved woman on the right panel, depicted as a labouring body carrying cane in the fields. The presence of her young child also labouring at her side creates a poignant portrait of disavowal of Black motherhood. Here Black childhood is characterised by limited life opportunities and denied by slavery’s dehumanising across generations. The third enslaved figure appears twice in the piece, with her face entirely cut out in the top right-hand side of the panel, then under-exposed in the bottom left, so that we cannot make out her facial features.

These figures have all been deprived of sight, as well as humanity and home. The blinding of the enslaved marks them out as tortured Black bodies that are fundamental to the imagining of the nation.18 Yet, they somehow refuse the naturalisation that reduces them to objects of scientific inquiry and violable flesh. Those who gaze upon them are denied clues to their emotions that might lie in their eyes and faces. The subjectivities and lived experiences that remain hidden from the gaze are therefore beyond knowability.19 This denies the viewer the captives as what Deborah Poole calls ‘image-objects’ through which racial difference is imagined, desired and othered.20 In some way, Blackness here holds the possibility of exceeding the meanings attached to it by the dominant gaze and becoming a void between object and subject, between looking and being looked upon.21 I also understand this space of unknowability as the calunga, a zone of Black cognition that is visible and legible only to those fellow survivors of the crossing and their descendants.

With all of the blinded figures in Paulino’s work, that void/calunga seems to conceal the presence of a second sight that allows for contact with the invisible, with the presence of the ancestors. This sight opposes the visual regime of the coloniser, under which the surveillance of enslaved bodies was fundamental to social control.22 The visualised power here comes from the legions of the dead, from a time-space of ancestrality that continues to sustain Black life in Brazil today. In her Poemas da recordação (2017), Conceição Evaristo writes directly about a time-space in which the ancestors are invoked to keep a different kind of watch over the enslaved and their descendants, as they navigate the process of settlement. Embodied knowledge and visions of Black futurity produce the quilombola space that Evaristo describes:

We dream beyond the enclosures. The field in which we sow is vast and no one, apart from us, knows that we also invented our own Promised Land. That is where we manage to sow our seeds. In our rugged fields – we know exactly how to tread its hills and plains – at every moment our ancestors watch over us and we learn with them how to walk the paths of the stones and the flowers.23

In Paulino’s work that dreaming allows for contact with a world invisible and unknowable to those who occupied and continue to occupy the Big House. This second sight continues to oppose coloniality’s visuality, but it does more than oppose. It visualises another form of quilombola power that comes from the dead and from mourning the dead. The site of mourning from which Black freedom and Black futurities may be imagined materialises as assentamento – a foundation, a sacred space, a form of record and a condition of possibility.

Assentamento allows us to glimpse what geohistories of the Americas might look like if they were narrated by Black women’s voices. It permits us to see how our vision of the world-that-scientific-racism-built changes when constructed from sites of knowledge of the enslaved and their descendants. One of the imperatives that propels Paulino’s work, and that of several emerging Black female artists in Brazil today, is to interrogate the role that European scientific knowledge played in the making of social realities and imaginaries. Their work develops strategies for unravelling those theories of Brazilian society and finding new ways to narrate more fully the spaces that colonialism and its refusals produced.

(De-)Natural(ised) History

In her 2016 work ¿História Natural?, Paulino explicitly challenges the ways in which dominant forms of scientific knowledge have construed and constructed Brazil. She creates an artist’s book that uses mixed methods to reference and question the content and message of a typical nineteenth-century naturalist text. One page of the text proclaims the positivist tenets on which the Brazilian First Republic was built: ‘O progresso das nações; A salvação das almas; O amor pela ciência’ (The progress of nations; The salvation of souls; The love of science). When we open the text to that page, we see only half of each of these doctrines as the rest of each statement is covered with a piece of textile. On folding back the textile, we can now read the whole of each proclamation, and the textile’s reverse side has been covered with the image of Portuguese azulejo tiles from which a trickle of red runs down like blood, as in Atlântico Vermelho. Now that the textile has been pulled back it also reveals a sketch that was only partially visible before and looked like it could be a globe. In fact, it is a skull that sits squarely in the middle of the page and overlays the text. Here positivist progress in Brazil is conjoined with the colonial order, sharing forms of necropolitical governance that sacrifice certain populations in the pursuit of modernity. The ‘salvation of souls’ speaks directly to the Jesuit mission in colonial Brazil to convert Indigenous peoples, one of the tools of the conquest of bodies and territories.

Sections of the book are divided into the expected classifications of a natural scientist’s text: flora, fauna and peoples of the ‘new’ lands. The physical and epistemic violence from which such texts emerged is tangible on every page. Under ‘Peoples’, a faceless Indigenous man (taken from the engraving ‘O retrato do índio Muxuruna’ from the album Viagem ao Brasil, 1817–20, by German naturalists Spix and Martius) flanks an enslaved woman who has also had her face cut out of the reproduced photograph. Without their faces both figures have become a generic ‘indian’ and ‘slave’, their experiences and subjectivities expunged by the caravels sailing the Atlantic on the azulejo design over which the figures are superimposed. However, Paulino’s Natural History?, with its provocative question mark, also invites us to contemplate more fully the ways in which these bodies became inscribed within what poet Marlene NourbeSe Philip calls ‘the text of events of the New World’. Philip describes a process of Black women’s bodies becoming text characterised by displacement and exploitation, but also the particularities of the places these bodies make: ‘the Body African – dis place – place and s/place of exploitation inscribes itself permanently on the European text. Not in the Margins. But within the very body of the text where the silence exists.’24 In Paulino’s work both figures occupy the silences of the calunga (where-the-sea meets-the-land) to decentre settler colonial epistemology. Here assentamento functions once again as suture; the ‘suture between two hermeneutical frames’ that have sealed off Blackness from Indigeneity and metaphorised the former in terms of the sea and the latter in terms of the land.25

The faceless, enslaved woman is reproduced elsewhere in the artist’s book with her face and upper body exposed. The notes made by Agassiz’s team classify her image as a phrenological portrait and her ethnic group as Mina Ondo.26 Paulino does not allude to this scientific classification, instead allowing her headwrap, necklace and facial scars to say more about her kinship identification than the scientists’ notes. In this sense, her body becomes her archive: the scars on her face perhaps an inscription of a time before capture; the adornments and headwrap perhaps alluding to a unique ethnic or regional identity; and her bodily exposure a testament to the extreme vulnerability of her condition as an enslaved woman.27 Her body-archive becomes ‘a kind of hieroglyphics of the flesh’ that talks back to the objectification of scientific knowledge.28

‘Assentamento’ provides a way to understand Black social and political life that acknowledges the embodied and everyday experiences and knowledge of Black women. It is memory work and it is place making, two inseparable endeavours that require(d) great creativity and courage and that underlie Black epistemologies. To recall Conceição Evaristo’s poignant affirmation of Black life: ‘They decided to kill us, but we resolved not to die (Eles combinaram de nos matar, mas a gente combinamos de não morrer).’29 On their violated bodies Black women inscribed that refusal in the face of displacement and trauma. They insisted on their personhood and the value of Black family, community, orality, belief-systems, lives and love. ‘Assentamento’ honours the imaginative archival practices of our foremothers that defy the silences of Black transcontinental histories. By rooting our ideation in this ever-renewing site of Black archival creation, we foreground different foundations of knowledge than those that are celebrated in the academy. We acknowledge the women who went before us, whose strength and inventiveness made us the artists, activists, thinkers and writers that we are today.

Rosana Paulino offers us assentamento as a vision for Black reimagining and remaking of society. Her generative notion of settlement is a precious gift that can help us reorient our thinking to centre the insubordinate geohistories of the Americas – the spaces of the calunga and the quilombo. At the core of that thinking let us position a lineage of labour by our fellow malungas, our kin and extended like-kin network, in putting down roots in diasporic soil. ‘Assentamento’ pays homage to this labour – physical, emotional, political – the labour of place-making, of social and biological reproduction, of knowledge production. One question that Paulino’s notion demands urgently of all of us in the diaspora is: what are the particular futures that we want that labour to call into being?

This is an extract of a longer piece by Lorraine Leu published in ed. Christen A. Smith and Lorraine Leu, Black Feminist Constellations: Dialogue and Translation Across the Americas, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2023. Republished with permission from the author and University of Texas Press.

Footnotes

-

Vincent Brown, ‘Social Death and Political Life in the Study of Slavery’, American Historical Review, vol.114, no.5, 2009, p.1247.

-

Stephanie Smallwood, ‘Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa to American Diaspora’, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008, p.191.

-

Rosana Paulino, ‘Critical and Curatorial Approaches to Contemporary Afro-Brazilian Art’, lecture, Center for Latin American Visual Studies, University of Texas at Austin, 18 August 2021.

-

Gilberto Freyre, The Masters and the Slaves: A Study in the Development of Brazilian Civilization, New York: Knopf, 1956.

-

Katherine McKittrick, ‘Plantation Futures’, Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism, vol.17, no.3, 2013, pp.3 and 9.

-

Keisha-Khan Y. Perry, ‘Geographies of power: Black women mobilizing intersectionality in Brazil’, Meridians, vol.14, no.1, 2016, pp.94–120.

-

Maria Helena Pereira Toledo Machado and Sacha Huber, Rastros e raças de Louis Agassiz: Fotografia, corpo e ciência, ontem e hoje, São Paulo: Capacete, 2010, pp.24–26.

-

Marisa Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016, p.16.

-

Avery F. Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008, p.xviii.

-

Denise Ferreira da Silva, ‘No-Bodies: Law, Raciality, and Violence’, Griffith Law Review, vol.18, no.2, 2009, pp.212–36. See also Lorraine Leu, Defiant Geographies: Race and Urban Space in 1920s Rio de Janeiro, Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020, p.115; and D.F. da Silva, ‘Towards a Critique of the Socio-logos of Justice: The Analytics of Raciality and the Production of Universality’, Social Identities, vol.7, no.3, 2001, p.422.

-

Carlos Eugênio Marcondes de Moura (ed.), A Travessia da Calunga Grande: Três séculos de imagens sobre o negro no Brasil, São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 2000, cover copy.

-

D.F. da Silva, ‘No-Bodies’, op. cit.

-

Lathabo Tiffany King, The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019, p.4.

-

Conceição Evaristo, ‘Da grafia-desenho da minha mãe: Um dos lugares de nascimento da minha escrita’, in Marcos Antônio Alexandre (ed.), Representações performáticas brasileiras: Teórias, práticas e suas interfaces, Belo Horizonte: Mazza Edições, 2007, pp.16–21.

-

Ibid.

-

Tairine Cristina Santana de Souza, ‘Corpos, memórias e saberes inscritos na educação nos terreiros de candomblé da Bahia no tempo presente’, MA thesis, Universidade Federal da Bahia, 2021.

-

R. Paulino, ‘Critical and Curatorial Approaches to Contemporary Afro-Brazilian Art’, op. cit.

-

Christen A. Smith, Afro-Paradise: Blackness, Violence, and Performance in Brazil, Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2016.

-

L. Leu, Defiant Geographies, op. cit., pp.101–02.

-

Deborah Poole, Vision, Race, and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World, Princeton, CT: Princeton University Press, 1997, p.7.

-

Nicole R. Fleetwood, Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011, p.6.

-

Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011, p.67.

-

C. Evaristo, Poemas da recordação e outros movimentos, Rio de Janeiro: Editora Malê, 2017, p.111. Author’s translation. (Original Portuguese: ‘Sonhamos para além das cercas. O nosso campo para semear é vasto e ninguém, além de nós próprios, sabe que também inventamos a nossa Terra Prometida. É lá que realizamos a nossa semeadura. Em nossos acidentados campos – sabemos pisar sobre as planícies e sobre as colinas – a cada instante os nossos antepassados nos vigiam e com eles aprendemos a atravessar os caminhos das pedras e das flores’).

-

Marlene NourbeSe Philip, A Genealogy of Resistance: And Other Essays, Toronto, Canada: Mercury Press, 1997, p.95.

-

L.T. King, The Black Shoals, op. cit., p.4.

-

M.H.P.T. Machado and S. Huber, Rastros e raças de Louis Agassiz, op. cit., p.94.

-

M. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives, op. cit., p.14.

-

Hortense J. Spillers, ‘Mama’s baby, papa’s maybe: An American grammar book’, diacritics, vol.17, no.2, 1987, p.67.

-

C. Evaristo, ‘A gente combinamos de não morrer’, Olhos d’água, Rio de Janeiro: Pallas, 2015.