When a work of art is neither conceptual, research-based nor abstract-formalist, then it tends to acquire a ‘fine art’ status. Such are the conditions of contemporary art, grounded as it is in theory, documentary and ready-made materials, research and critical narrative. The place of the image within this exists as something like a film-still or digital emulation, something that can afterwards always be readily and endlessly reproduced. Such a sense of the randomness and contingency of an image can be seen as historically prefigured already in surrealism. As Rosalind Krauss forcefully argued in The Optical Unconscious, the drawings of Max Ernst and their figurative imagery had nothing to do with an image in its proper sense but have ever functioned as a machine of the unconscious. 01 The image in this case is machinic, critical and information-based, it is cyber-data or an archival trace.

In the ‘digital age’, the image loses the dimension of its mimetic inheritance, it can no longer function as a metaphoric symbolization of reality. The inference that it can again become a poetic symbol, a monumental emblem or an epitaph does not appear credible. It is in and against this context that Thea Gvetadze’s solo exhibition ‘Becoming Thea Merlani’ at M HKA inserts itself. 02 In it, Gvetadze’s images achieve a quality that surpass the realistic mirroring of reality while resisting becoming an abstracted sign. In her work, the image stands as an emblem and monument for things, persons, situations: for, we might say, Being as such. Such qualities are characteristically linked to hieratic architecture or monuments, to historical or mythological events more closely than they are to painting and its associated genres. The reality that Gvetadze reveals is the fatal and irreversible encounter of human beings with things – be they nature, human stories, history of her family or random passers-by.

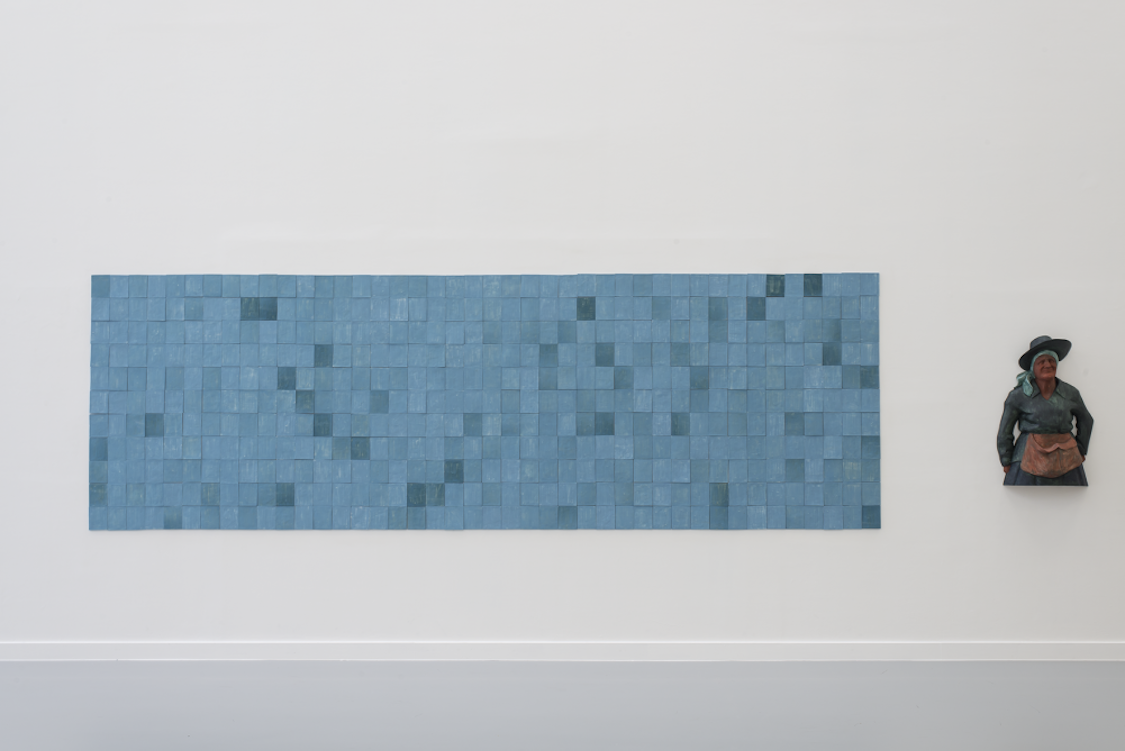

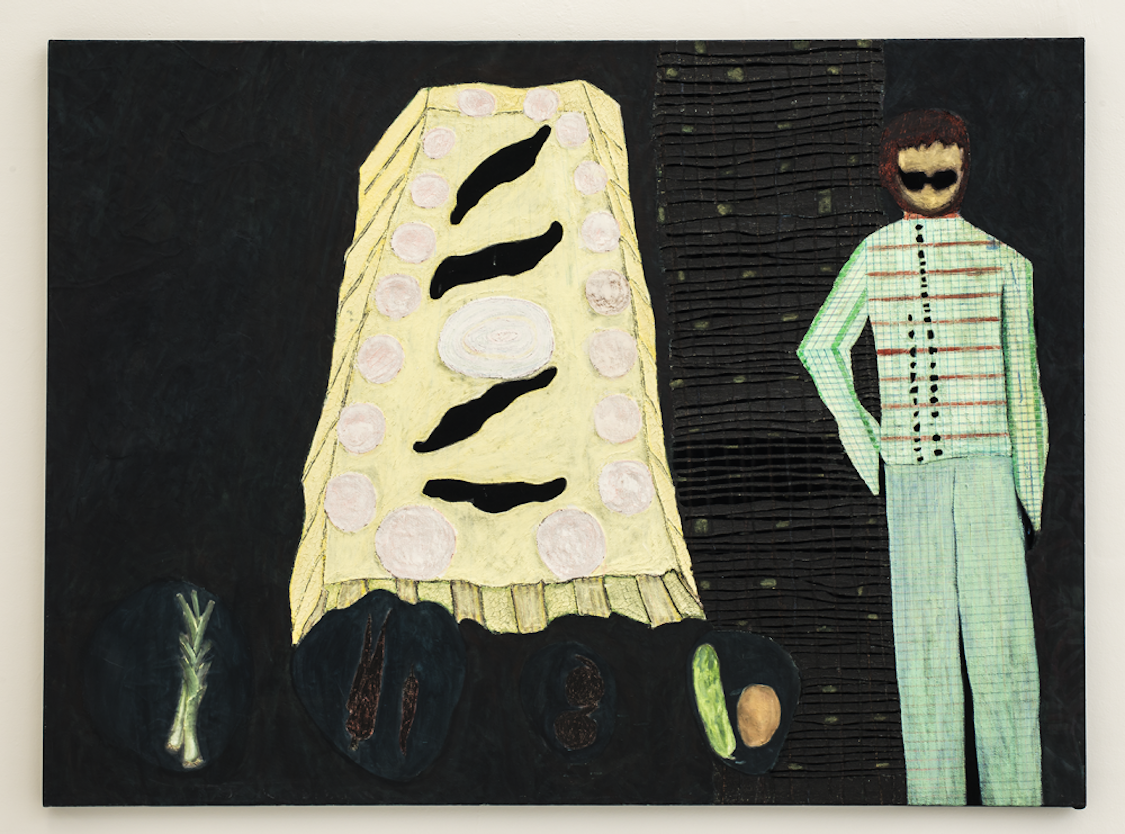

Three works open up onto this proposition, each of which deals in its own way with the delicate link between sorrow and jubilation. The first is the wooden relief Cabbage Hat (2018) that shows a simple sculpted head of a peasant woman, partially covered by a cabbage leaf. As the artist herself recalls, she saw this sales-woman at the market; the woman seemed robust, vital and energetic. But when the artist asked her why she kept a cabbage leaf on her head, the woman answered that the leaf was meant to soothe her unbearable headache, which she had to endure on a daily basis at her stall in the market place, in the midst of merciless sun. The piece is not simply a sculpted portrait, but a monument and emblem of the sales-woman’s endurance and stamina. Becoming Thea Merlani (2018) features another peasant woman, this time she protrudes from the wall as a life-sized relief, almost hovering in the air. Reminiscent of historic Dutch painting and Spanish polychrome sculpture, the wooden body monumentalises an old woman selling bagels at the beach. The final is the painting If it takes forever, I will wait for you(2012). As with the others, this work also pays homage to an old woman, this time she shuffles from the edge of the frame into the noise and entertainment of a seaside-resort, desperately and perhaps unsuccessfully attempting to sell a small bundle of flowers. Scanning one’s eyes across each of these works, it is possible to discern a deep mixture of ontological sorrow with something resembling a gratitude to Being. Each of the figures, living the ‘poor’ life, persevering themselves through their incessant labour, have no names, yet they are immortalized in the artist’s monumentalization of their disinterested benevolence. As the artist claims, these stoics of labour express their courage in the experience joy in the midst of hard work and exhaustion. In the gallery of Gvetadze’s characters these candid creatures represent utter generosity, they are the sages that emanate gratitude against the backdrop of hardship. This is the reason why the gaze of the artist towards such characters is never straightforwardly a social critique or a documentary research.

All that said, it is not poverty that becomes a virtue in Gvetadze’s depiction of her protagonists, rather it is candidness and initial ontological overtness that comes to the fore among the ‘simple people’. Parallels can be here drawn with Pier Paolo Pasolini, who was often criticized for his idealization of peasantry. In one of his interviews, to the question who were the people he liked most, the director answered, that he liked the ones that ‘perhaps never reached the fourth grade’: those ‘very plain and simple people’. 03 This was, as he argued, because only they represented the purity of escape from the petit-bourgeois life, and only they were able to bear the capacity of utter grace due to being excluded from conventional ‘culture’, technology and its various forms of utilization of human life. Paradoxically, precisely such candidness, according to Pasolini, was able to carry the value of true culture and ethical grace.

Such stance, although rare and unique, seems important in that it implicitly defies the hypocrisy of contemporary critical thinking in art. Simple-heartedness for Gvetadze is rather a sophisticated achievement than any disenfranchised state to be revealed, highlighted and exposed by enlightened intellectuals in the form of a social critique. Consequently, this ‘simple’, ‘poor’ life is not lacking in knowledge, (technical) skills or other forms of wealth. Quite the contrary, it can instruct the enlightened, immaterial post-industrial workers about things withdrawn from the world of creative industry, of technocratic essentialism and optimization. Contemporary art and its institutions initiate the critique of neoliberal semio-techno-capital and defy its vices, but the quality of Being and human relations in the name of which this critique could be undertaken is either unknown or lost in them.

Against the depiction of poverty, hardship and labour in any naturalistic way – the type that contemporary art so frequently pairs with condescension, considerate pity and middle-class ‘progressive’ critique – Gvetadze endows this ‘poor’ Being with utmost beauty, with sophisticated decorative elegance and monumental grandeur, enrobing her characters in most exquisite costumes. The impoverished lady selling flowers in If it takes forever I will wait for you, wears a bright and thoroughly decorated garment. Such preoccupation with adornment in Gvetadze’s paintings, reliefs and installations is not mere mannerism; but, however paradoxical it sounds, the garment uplifts the transient human existence and its squalor to generality, revealing the artist as the protector and gratifier of precarious bodies, and endowing these underestimated invisible creatures with what they truly deserve: care and veneration. Sophisticated decoration and adornment turn the otherwise mortal bodies into eternal emblems.

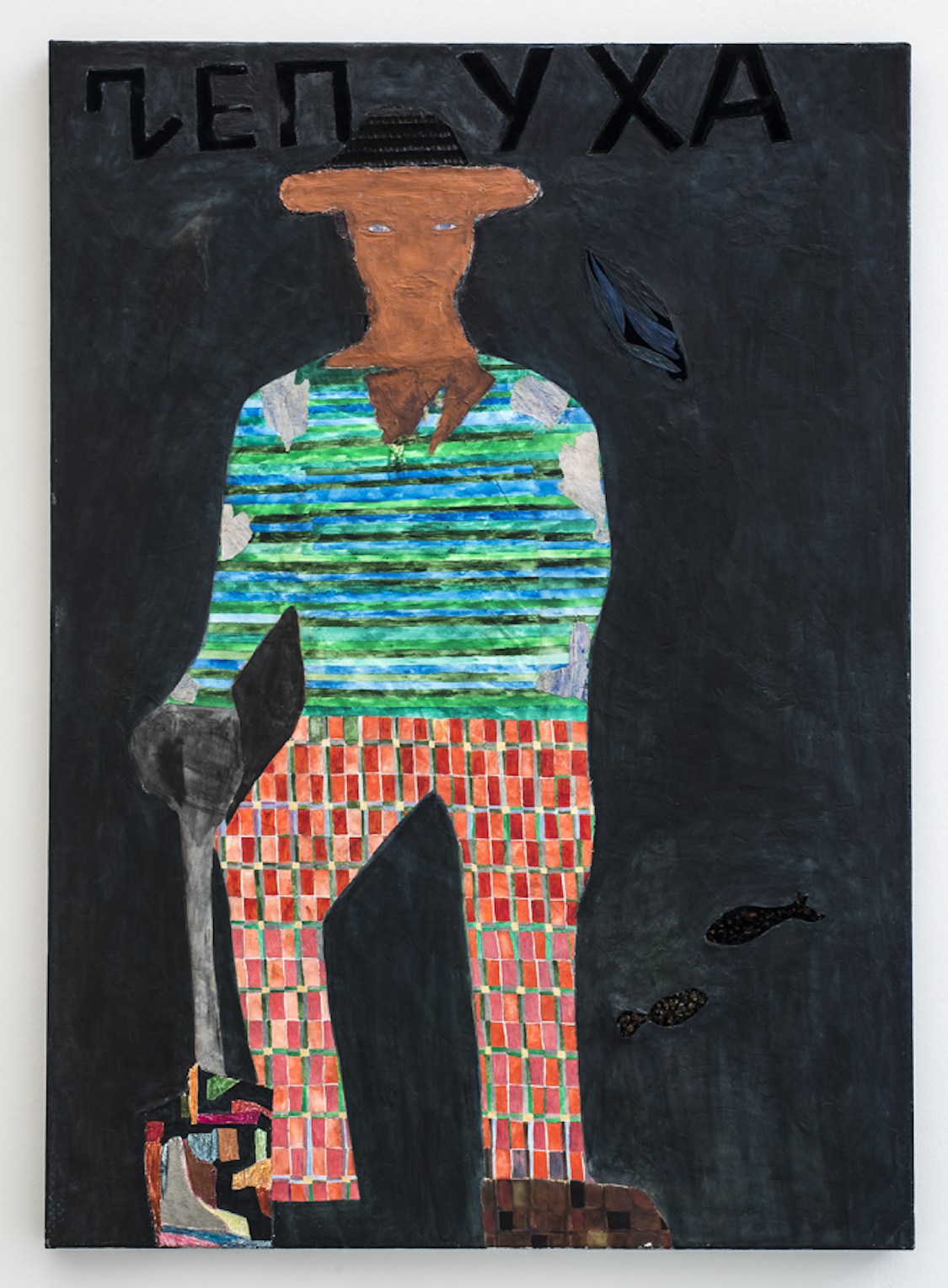

Yet other protagonists in Gvetadze’s gallery of grace are male vagabonds, as, for example, in Chepukha or Shavi Shotebi (both 2012). Mischievous and mysterious, these reckless wanderers appear to be poets, despite seemingly having never written a word; in them, melancholy and irony merge with grace and naïveté. They bear a true knowledge about Being and are the mute nomadic heralds of its poetic dimension, indifferent as to whether anyone acknowledges them as such. The prototype of the painting Chepukha (which translates from Russian as ‘fiddle-de-dee’) was a janitor that Gvetadze met while he was cleaning her neighbour’s yard. The man introduced himself in conversation with the artist as Chepukha, telling her that his mother gave him this nickname since she believed life was nothing but fiddle-de-dee.

The third group of Gvetadze’s gallery concentrates on the family and its painstaking inexorability. The paintings, reliefs and readymades that populate this group become epitaphs of an elusive time, shorthand attempts to grasp the most precious moments that had forever been lost. The climax of such history is a diptych of two readymades: Esophagus Foreign Bodies and Trachea Foreign Bodies (both 2014). These two works are comprised of personal displays belonging to Gvetadze’s father, the surgeon and pulmonology specialist Dr. Paata Gvetadze, of objects accidentally swallowed by children, that he removed from their throats and trachea. Each item therefore can be considered a life saved. Paata Gvetadze passed away in 2014 and these displays of lives saved by him become a monument to his commitment and dedication as a doctor.

Alongside this, the principal and largest monumental piece around which the whole exhibition moulds itself is a ceramic installation scattered over the wall Zeda Tsinsvla (2017). These sculpted reliefs were inspired by a bus stop called after the village Zeda Tsinsvla(georg. ‘Supreme Forward’) in Adjara, Georgia, adjacent to the cemetery, where Gvetadze’s family members are buried. The bus stop is decorated with mosaic from the Soviet 1960s, featuring fertility and bountiful harvest. Its uplifting depiction of life sits in drastic contrasts with the death and sorrow of the graveyard.

As a test case for much of Gvetadze’s work, Zeda Tsinsvla picks out and exaggerates particular elements of the mosaic and, acquiring the form of sculpted reliefs, these almost abstracted emblematic forms are then stuck to the wall. Historically, Soviet murals and mosaic frescoes, no matter where in the Union they were from, were used to depict the production output of each republic. Agricultural imagery was found in southern rural regions, cosmos or science activities in naukograds, and labour and production imagery was found in industrial cities, factories and plants. The murals found in Soviet Georgia had traditionally featured the ‘national’ traits of the southern republics: fertility and abundance.

Yet what makes these Soviet frescoes stunning and irresistible today is not their descriptive realism; rather, it is their generalization and typologization of an otherwise versatile life and activity. They manage to simultaneously distil the multiplicity and singularity of features and draw them up to the typical and generalized concept-image, encompassing all modes of an object, of a human being, of a profession or of labour activity, as if it were possible to depict the fruitness of a fruit, cloudness of a cloud, faceness of a face or the human beingness of a human being.

Gvetadze manages to extract even greater generality from these already typical ‘icons’ and bring the objects, once belonging to the composition of the fresco, to even stronger eidetic and emblematic purity. The wall in which these epiphenomena stay suspended is made of clay and terracotta paint, becoming another ‘thing-in-itself’ – the wallness of a wall, rather than merely a backdrop for exhibited objects.

Reflecting on the aftermath of the now-closed ‘Becoming Thea Merlani’, one cay say that it reveals itself to have not simply been a show of the most outstanding artistic work by Gvetadze; it also functioned as a reminder that life is broader than merely being a material for our often-superficial critique. The place of art within this is not merely a repository for images, narratives, artefacts, cognitive skills and judgments, but it is first and foremost a means of gratitude and labour of its monumentalization.

Footnotes

-

See, especially, chapter two of Rosalind Krauss, The Optical Unconscious, Cambridge, MA and London: The MIT Press, 1994.

-

‘Becoming Thea Merlani’, 12 May–2 September 2018, M HKA, Antwerp. Following her studies at the Ybilisi State Academy of Art, the Rietveld Academy and the Düsseldorf Art Academy, Thea Gvetadze now lives and works in Tbilisi, Georgia.

-

See ‘Pier Paolo Pasolini Speaks’, available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5IA1bS1MRzw.