In the second part of her essay on Maria Eichhorn’s 2016 exhibition at Chisenhale Gallery, Afterall Writer in Residence Anahita Delcorde discusses the politics of time giving and the difficulties of articulating an emancipatory art practice with regards to labour in the art world.

Limits and Contradictions: Can You Really Gift Time?

According to Maria Eichhorn, the ‘show at the Chisenhale Gallery is a way of giving time back to the staff who work there: when they accept this offering, without their wages being suspended, the work will emerge’. 01 But the idiom ‘giving time’ should be interrogated here: how, exactly, is time given?

In Given Time: I Counterfeit Money (a text often mentioned by the artist in the exhibition’s publication), Jacques Derrida argues that ‘to give time, the day, or life, is to give nothing, nothing determinate, even if it is to give the giving of any possible giving, even if it is to give the condition of giving.’ 02 Time cannot be possessed, but rather opens the space for new ways of filling time. For Derrida, ‘one can only take or give, by way of metonymy, what is in time’. 03 Giving time signifies leaving time for something else: in Eichhorn’s exhibition, this something is the opposite of work, the latter understood here as tasks performed in order to sustain, spread and embody the art institution.

To give time without wishing anything in return is to give time as a gift. Eichhorn does not expect the gallery staff to work, nor to tell her how they will spend their time. The gift here is established in the will to suspend exchange: work productivity is not expected for the wage that the staff will receive. The gift of time expands the present: in Isabell Lorey’s words, giving time means a ‘non-capitalisable gain in time for recipients’. 04 Time is made available to the staff in a way that is self-determined. As such, according to Lorey, the equivalence of a productive return ‘can no longer be estimated’. 05

However, even though Eichhorn trumps the relationship of exchange by introducing the idea of paying leisure or free time, dependencies between the different parties are not completely absent, or outside of financial power structures. Following Derrida’s analysis, a genuine gift requires anonymity: it suspends exchange through masking the identity of the person ‘giving’ (in order for it not to be perceived as a ‘good deed’ and thus become profitable), and by virtue of not being perceived as a gift by the party receiving it. Otherwise, the gift reintegrates the economic logic of exchange and potential profitability and will, as such, no longer be a gift. What happens, then, when the gift of time is part of an artistic work? In 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, the staff ‘make’ the work, paradoxically, by not working; a work for which Eichhorn was commissioned (and thus paid). The staff is reemployed in another manner. It could be argued that they are actually working for Eichhorn, since she requires them to do something, which consists in not doing anything, in order for the artwork to be realised. To a certain extent, Eichhorn might be considered a manager, as her own labour, is not totally withdrawn: she dictates the structure of time and work of the Chisenhale Gallery’s employees. It could then be argued that Eichhorn, through her gesture, ‘owns’ the labour of the gallery staff, even though the only requirement is for them not to perform the activities they are usually paid for by the institution. The artistic work of giving time, as such, is in essence a return: the artist is forcing the staff to ‘strike’ in order for her work to emerge (an aspect which she is fully aware of). 06 In this case, the gift clearly has an author and its conditions of production are controlled. Having an author, the artwork is not really a ‘gift’ of free time.

In her essay ‘Delegated Performance: Outsourcing Authenticity’, Claire Bishop investigates the question of authorship in relation to artistic ‘situations’and performances. She writes, ‘the performers also delegate something to the artist: a guarantee of authenticity, through their proximity to everyday social reality, conventionally denied to the artist who deals merely with representations.’ 07 To a certain extent, the gallery staff can be understood as actors in Eichhorn’s artwork: they help define the work as authentic. Yet, this authenticity is highly ‘directed’: for Bishop, ‘they confer upon the project a guarantee of realism, but do this through a highly authored situation’. 08 As such, the authorial position of the artist remains central and unchallenged. The Chisenhale staff find themselves in a complex position regarding the work: at the same time individuated (since specific to the Chisenhale Gallery context) yet metonymic of wider labour conditions; live and mediated; able to choose and yet forced into a specific role. The labour, not dedicated to the institution, finds itself used for the execution of Maria Eichhorn’s art.

Furthermore, is it really possible to fully suspend practices that spread the institution, and escape the intertwining of the private and the professional? Or is Eichhorn here only defusing them temporarily? Emails may have been deleted during the exhibition, but project deadlines have most certainly not. As seen in part I, labour tasks are now much too enmeshed in workers’ everyday lives. Even though the title of Eichhorn’s work reinstates the necessity of a separation between work-time and leisure-time, their blurring is difficult to subvert. As Isabell Lorey explains, now, ‘every conversation, every smile can mean capital, symbolic or monetary – both for the persons who maintain contact with the staff, and for the individuals who make up the staff’. 09Eichhorn’s work was intended as an act of resistance against neoliberalism’s occupation of every corner of life; yet, due to its unescapable rooting and the quite limited duration of the exhibition, the suspension of the activities that extend the work (here the art institution) into private life, seems quite impossible. Over five weeks, it seems difficult to reinstate a clear division between work and leisure, when the staff embody the art institution, so as it’s difficult to re-establish a life-work balance when private life is constantly hijacked by employers.

Spectres of precariousness

Maria Eichhorn’s artwork solely focuses on the salaried employees of the Chisenhale Gallery. However, its staff is not limited to them: at the time of the exhibition, and like most art institutions, the Chisenhale Gallery ran a volunteer program.10 Volunteers, mostly art students and graduates, usually assisted during specific events or openings, and were not paid. Not being paid has become a normalised situation, justified by the idea of an economy of learning. Indeed, for Lorey,

the promise of learning something while at work legitimizes the non-payment of that work… Especially in the Anglo-Saxon world it has become normal for the ‘learner’, too, to become not only more and more financially indebted, but also to incur moral debts for the education of one’s increasingly long education. 11

The volunteer scheme standardises the idea that individuals now need to be grateful for having the opportunity to learn, and thus do not necessitate to be paid, since they are not yet ‘professionals’. Volunteering, traineeships12 and zero-hour contracts (which usually apply to freelance technicians, for example, working on the installation and de-installation of an exhibition) have normalised the unstable realities of precariousness. To use Hito Steyerl’s words, late capitalism has led to the rise of a new class, the ‘educated precariat’.13 Art labour today is increasingly casualised and fragmented into a variety of precarious modes of work: internships, trainings, freelance jobs, zero-hour contracts, multiple part-time jobs and poorly-paid side projects. Eichhorn’s work does not consider these new forms of labour, which are direct consequences of neoliberalism. On the contrary, one could even argue that she weakens their position, as zero-hour contract employees have to find work elsewhere and see their financial revenue shift consequently during the time of her show. Implicitly, Eichhorn is not challenging the new existing structures of waged labour and new forms of exploitation. She is subverting an order for those, who, ironically, have the most stable positions in the arts.

Furthermore, Eichhorn decided the work should be transmitted and explained through a symposium and dense publication around the work’s main ideas, both accessible online. Several elements of the Chisenhale Gallery actually remained ‘open’: the website where the symposium and online publication were uploaded, and the gallery’s social media accounts where a gallery statement was posted. Interestingly, Gilles Deleuze situated the exploitation of individuals in late capitalism and its increasing technologisation. 14 This nexus was left ‘present’ in Eichhorn’s piece, serving as a space for the explanation of the work. This online presence appears to be essential in ‘spreading’ the artwork as such. According to Claire Bishop, ‘today dematerialization and rumor have become one of the most effective forms of hype’. 15 Dematerial forms of art historically claimed that their evanescence and non-materiality allowed them to escape commodification; yet it is these very same characteristics that ultimately augmented immaterial art’s value in terms of cultural prestige. The work’s value is reinforced by the awareness around its happening.

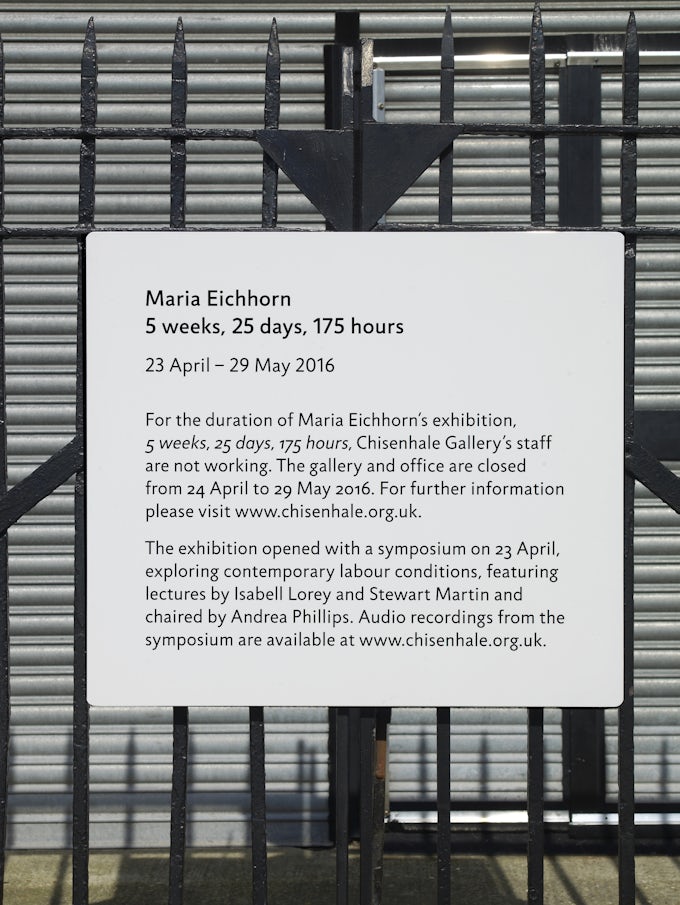

This aspect is also taken up by Hito Steyerl in ‘The Terror of Total Dasein’, published in her collection of essays Duty Free Art. For Steyerl, art labour has shifted from the traditional idea of being tied to the production of objects to an ‘economy of presence’ of the artist. According to Steyerl, ‘the idea of presence invokes the promise of unmediated communication, the glow of uninhibited existence, a seemingly unalienated experience and authentic encounter’. 16 Eichhorn was present during the symposium and the audience was there to discuss the work with her. Eichhorn’s work, as such, does not escape what Steyerl identifies as the market economy of presence in art. The statement on the gates of the Chisenhale Gallery is quite revelatory: it suggests going listen to the symposium, in which the artist interacts with invited academics and the audience. Presence maintains the aura of the work, as it’s not infinitely reproducible, but constitutes what appears to be an authentic experience. In a time when nobody has time anymore, making time to go to an event adds to the importance attributed to the presence of the artist, as an exceptional encounter, that has to be lived in person. For Steyerl, ‘the aura of the unalienated, unmediated and precious presence depends on a temporal infrastructure that consists of fractured schedules and dysfunctional, collapsing just-in-time economies’. 17 Technology thus enhances this economy of presence by serving as an immortal ‘proxy’ for the artist’s presence.

Closing Thoughts: Contracts, Critique and Whatnot

At the 2010 Whitney Biennial, American Conceptual artist Michael Asher’s work consisted in his request that the biennial be open 24 hours for seven days. The work, which relied on the idea of ultimate accessibility to welcome wider audiences, was finally limited to three days, as the museum did not have the budget to keep the galleries open. The act of openness was trumped by the rampant lack of funding of cultural institutions, and by consequence, the impossibility to pay extra staff.

Maria Eichhorn’s work at the Chisenhale Gallery appears as an opposite intervention, consisting in the closure of the gallery space for five weeks. However, it might be argued that Eichhorn’s work similarly puts the finger on issues surrounding present-day conditions of exhibiting art. The artist interrogates the value assigned to specific time, to work, in order to deconstruct our understanding of labour and leisure. ‘Doing nothing’ as such becomes an important tool to subvert financial and social power structures.

This set of issues is of course reminiscent of past Institutional Critique. Eichhorn’s gesture can be put in parallel with those of 1960s conceptual artists who wished to produce art that, through dematerialisation, would escape the market and the gallery system which were seen as sites of corruption and distortion of art.18 However, in the 1980s, immaterial artworks started themselves to be increasingly purchased. The act of establishing artist’s contracts – Seth Siegelaub’s own contribution – strangely backfired as it ‘reduced’ art to its legal organisation and institutional validation. Non-object-based art was first considered as a revolutionary tactic to escape the market and the institution, yet ultimately succumbed to it. As Lucy Lippard wrote,

It seemed in 1969… that no one, not even a public greedy for novelty, would actually pay money, or much of it, for a Xerox sheet… Three years later, the major conceptualists are selling work for substantial sums here and in Europe… Clearly, whatever minor revolutions in communication have been achieved by the process of dematerializing the object… art and artists in a capitalist society remain luxuries. 19

In the 1980s, right when this shift was being operated, Eichhorn was a student at the Hochschule der Künste in Berlin and was fully aware of this reversal of circumstances. 20 She investigated then Conceptual art’s legacies and conducted a series of interviews with major Conceptual artists. 21 Eichhorn’s interest in and knowledge of Conceptual art indicate the link between her practice and the legacy of Institutional Critique. Following Alexander Alberro, Institutional Critique has confronted the institution of art as not being sufficiently committed to the pursuit of the public function which had brought it into existence in the first place, and related issues of representation.22 The aim was to expose how political, economic and ideological interests faced and influenced the production of public culture, and how corporations intervened into the presentation of art. However, as Hito Steyerl states, critique has since risked becoming ‘an institution itself, a governmental tool which produces streamlined subjects’. 23 Through a Marxist prism, critique can be read as a bourgeois strategy to criticise the institution, without truly destroying its foundations, and instead, ending up being co-opted into what Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello qualified as the ‘new spirit of capitalism’. 24 Institutional critique has become the site for a critique that does not change the structures of exploitation, as it works within the institution itself, and could not exist without it.

5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours is an exhibition and an artwork that does not lend itself to be easily defined: the closure of the space is not so much about the institution’s link with the art market than about a broader reflection on the topic of labour power and its exploitation. Even though the work is unable to fully extricate itself from the economy of the arts sector, we could wonder if such a project is currently even possible. A total withdrawal from the (arts) economy and the power structures at play within the organisation of (art) labour appears to be unsurmountable, when enacted within the micro framework of the single institution.

Maria Eichhorn’s 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours is a practice of criticism that is not unaware of its own lacks. It might be temporary and incomplete, but it still offers an invaluable contribution: that of disrupting, even though briefly, the oppressive temporal structure of the neoliberal order, and ultimately, opening up a time for radical daydreaming.

Footnotes

-

Himali Singh Soin, ‘Interviews. Maria Eichhorn talks about her solo exhibition at the Chisenhale Gallery’, Artforum, 14 April 2016, available at https://www.artforum.com/interviews/maria-eichhorn-talks-about-her-solo-exhibition-at-chisenhale-gallery-59479 (last accessed on 23 November 2022).

-

Jacques Derrida, Given Time. I, Counterfeit Money (trans. Peggy Kamuf), Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1992, p.54.

-

Ibid., p.3. Emphasis original.

-

Isabell Lorey, ‘Precarisation, Indebtedness, Giving Time: Interlacing Lines Across Maria Eichhorn’s 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours’ in Polly Staple (ed.), Maria Eichhorn, 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours, London: Chisenhale Gallery, 2016, p.48, available at https://chisenhale.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Maria-Eichhorn_5-weeks-25-days-175-hours_Chisenhale-Gallery_2016.pdf (last accessed on 26 October 2022).

-

Ibid., p.47.

-

For Eichhorn, ‘work is suspended (ausgesetzt), temporarily interrupted, thus becoming the focus of attention. It becomes exposed to the gaze, to attentiveness. The term “aussetzen” (to suspend, to expose, to abandon, to find fault with, or to strike) becomes active, operative and effective in its multiple meanings. But this strike is not chosen as I have imposed it.’ Katie Guggenheim, ‘Maria Eichhorn in Conversation with Katie Guggenheim’, in Mathieu Copeland, and Balthazar Lovay (ed.), The Anti-Museum: An Anthology, Fribourg and London: Fri Art and Koenig Books, 2017, p.136.

-

Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London and New York: Verso, 2012, p.36.

-

Ibid., p.37.

-

I. Lorey, ‘Precarisation, Indebtedness, Giving Time: Interlacing Lines Across Maria Eichhorn’s 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours’, op. cit., p.47.

-

Calls for volunteers stopped in July 2017 when the Chisenhale Gallery announced opportunities for paid event staff.

-

I. Lorey, ‘Precarisation, Indebtedness, Giving Time: Interlacing Lines Across Maria Eichhorn’s 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours’, op. cit., p.39.

-

Chisenhale Gallery also ran a traineeship from 2013 to 2019, which was paid and lasted one year: https://chisenhale.org.uk/programmes/curatorial-trainees/.

-

Hito Steyerl refers to this new class in her essay ‘International Disco Latin’, in Duty Free Art, New York: Verso, 2017, pp.135–42.

-

Gilles Deleuze, ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’, October, vol.59, Winter, 1992, pp.3–7.

-

C. Bishop, Artificial Hells: participatory art and the politics of spectatorship, op. cit., p.229.

-

H. Steyerl, Duty Free Art, op. cit., p.24.

-

Ibid.

-

Elizabeth Ferrell, ‘The Lack of Interest in Maria Eichhorn’s Work’, in Alexander Alberro and Sabeth Buchmann (ed.), Art After Conceptual Art. Cambridge, Mass. and Vienna: MIT Press and Generali Foundation, 2006, p.203.

-

Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997, p.263.

-

E. Ferrell, ‘The Lack of Interest in Maria Eichhorn’s Work’, op. cit., p.208.

-

Maria Eichhorn, The Artist’s Contract: Interviews with Carl Andre, Michael Asher, Daniel Buren, Paula Cooper, Hans Haacke, Jenny Holze, Adrian Piper, Robert Projansky, Robert Ryman, Seth Siegelaub, John Weber, Lawrence Weiner, Jackie Winsor, Köln: Walther König, 2009.

-

A. Alberro, ‘Institutions, Critique, and Institutional Critique’ in A. Alberro and Blake Stimson (ed.), Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2009, p.7.

-

H. Steyerl, ‘The Institution of Critique’, in A. Alberro and B. Stimson (ed.), Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artists’ Writings, op. cit., p.486.

-

Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello, The New Spirit of Capitalism (trans. Gregory Elliott), London: Verso, 2017