In her first solo institutional show, London-based Zimbabwean-born painter Kudzanai-Violet Hwami presented a series of works reimagining her country of birth.01 Spread across two rooms in London’s Gasworks, the exhibition seeks out the spirit of home, after her first trip back to her native land as an adult, with acute attention to the gaps emerging from the prolonged spatio-temporal rupture of diasporic experience. Of the many moments that can be reflected upon to understand Zimbabwe, Hwami focuses on those concerning celebration, the quotidian of family life, the fluidity of dream space, and the preparations for, and enactments of, ritual practice. The works presented speak to spiritual encounters and how personal and family histories can be enmeshed, co-opted and denied to support national and historical narratives, both those of the colonial regime (1889–1965) and the fabulations of post-colonial politics. The paintings open up dialogues between various archives: of the family, those aligned with the activities and agendas of the colonial administration, and the rapidly generated and shared digital images of social media. Through these dialogues, the boundaries of self are up for question.

Taking its title from the distance between Kwekwe, Zimbabwe, Cape Town, South Africa, and the London gallery, the indirectness of this route requires attention. It references not only the artist’s personal trajectory – a Zimbabwean childhood, a South African adolescence, and a British adulthood – but also a familiar pattern of migration. The routes between Zimbabwe and South Africa are well-drawn and they indicate a particular, politicised, temporal orientation. For South Africa-based Zimbabwean writer Panashe Chigumadzi, to ‘grow up in the body of a young black woman moving between Zimbabwe’s post-independence and South Africa’s post-apartheid is to understand that time does not erase that history’. 02 With this understanding, Chigumadzi’s exploration of home is a deep dive into expansive histories and national myth making, guided by family stories and attuned to the time lost in diaspora. Similarly, Hwami seeks guidance in the intimacy of the familial, without clarifying its boundaries, producing a body of work that reflects common trajectories of movement and established relationships with histories in the aftermath of political, social and economic upheavals that are inextricable from family history and life experience.

Interacting with the show first through the on-site performance of another London-based Zimbabwean woman, poet Belinda Zhawi, enabled a particularly rich initial reading. 03 In her performance, Zhawi’s words, songs, and samples provided a soundscape that further expanded the reach of Hwami’s canvases, implicating the ‘here’ of the South London gallery in the here/there of Zimbabwe. Performing in front of two 120 x 120cm oil paintings, Sitting by Sekuru’s Grave (2019) and Medicine Man (2019), Hwami’s speech and song meditated on the possibilities of knowing foreclosed by distance, the types of memories that always persist, and the tensions between making a home somewhere and being off a place. Like the archival assemblages that proliferate in Hwami’s predominantly large-scale, colourful canvases, Zhawi provided sonic fragments that spoke to the ‘hauntological’ dimensions inherent in all recorded music and the archive. Mixing recordings of Shona speech, English, her own voice, that of others, and the soundscapes of various locations, her use of samples mirrored Hwami’s established processes of producing paintings from projected digital collages. Made with a combination of found images, family pictures and photographs taken by herself, in Hwami’s canvases, collecting, recording, and arranging give way to the gestural fluidity of paint. This fluidity melts into Zhawi’s looping of the live and recorded, with Zhawi’s glitching, repetition and fading reflecting the tensions and synergies of the archive, the traces of painterly expression, and the presentness of the materiality of painting.

In Sitting by Sekuru’s Grave, a middle-aged woman sits soberly, positioned in the centre of the canvas on a blue floor, legs straight with the soles of her shoes visible. This encounter by Sekuru’s grave could either be one mined from family archives, represent a contemporary found photograph, or be one of the images taken by the artist. It raises the question of the ‘when’ of the archive. 04 Could the archive be from an hour ago? 05 The grave to which the title refers is not visible anywhere on the canvas, except perhaps in the expression of the sitter that may point towards mourning. In Shona, the word sekuru is a broad signifier of respect and kinship, simultaneously meaning uncle and grandfather. Sekuru is also a prefix used to refer to certain great ancestors. This ambiguous male elder represents a biologically and temporally expansive notion of kinship. The intimate tangle between the historical, political, mytho-spiritual, and familial is always present in sekuru, and the corresponding feminine form mbuya. The invocation of this unseen, departed figure through the title of the work pulls into frame questions of liberation. In the Zimbabwean context, the mother of the nation, Mbuya Nehanda, 06 is a centuries-old spirit whose medium, along with Sekuru Kaguvi, another medium, led the first Chimurenga(‘revolutionary uprising’) against the colonial regime in the late Nineteenth century. As such, imbedded in the kinship invoked by this word is the question of freedom. The ambiguity of Hwami’s relationship to the titular sekuru puts her in correspondence with those of the liberation struggle who ‘have led men and women in ways big and small, ahead of their time, defiant of the bodies limits.’ 07

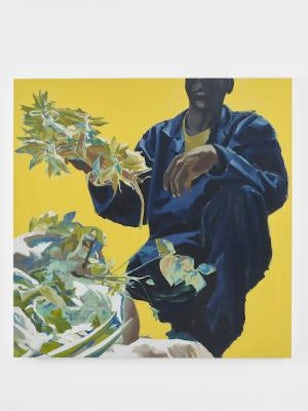

Medicine Man pictures the assistant to the healer at Dzimbanhete, an artist-run space on the outskirts of Harare. 08 The yellow of the t-shirt under his overalls is repeated in the yellow of the canvas’s background, giving the painting a vibrancy that fills the room. The placement of Medicine Man and Sitting by Sekuru’s Gravetogether creates a relay between various familial and spiritual lineages. A medicine man is not only a healer of the body; he is a keeper of knowledge, a diviner, a collector, a narrator. He is a manager of expansive lengths of time beyond the logic of linearity or the limits of the individuated self. The exuberance of Medicine Man’s yellow is repeated in another large canvas, Shona Boy with Dove (2019), placed in the smaller room and visible from much of the first through the opening that links the two spaces. This boy’s gaze, wide, gentle, but steely, follows you across both rooms. Shown from hip to forehead, this giant little boy’s dove, painted with a lighter touch than his friend/captor, looks up to him as he unrelentingly looks to us. The scale of this bird of peace is large, for both the canvas and the boy’s hand. The use of plants as motif is familiar in Hwami’s œuvre, as can be seen in older works such as Mwana wa Mukami (2016), Dance of Many Hands (2017), Sekuru Koni (2017), and Lotus (2018). In Shona Boy with Dove, as in a small, untitled canvas hung on the wall parallel to it and opposite Medicine Man, what looks like a small banana plant is represented. Across the show these various vegetals – those that enliven domestic life, the magical/healing plants of the medicine man and the nutritious banana plants needed to maintain body functions – remind us of the importance of plant life to human life.

Next to the boy, on an equally large canvas, is Dreamcatcher (2019). A full-length painting of a seated older man with his cane, both feet bare, the right foot oversized and painted with little detail, if any. He looks out of the canvas with an expression that is difficult to read, his gaze does not follow and is content within the world of the painting. The narrow sliver of abstraction across the right side of the canvas, in black and white with small areas of aqua, red and orange, pointing to the different forms that dreams may take beyond the figurative, their potential for amplification and opening up of different modalities. 09

The coral colours of the sitter’s background are emptied of all details in the room, but floating images, in negative, are painted above each shoulder. Over his left shoulder, a fragment of a ‘Made in Rhodesia’ label points both to the closeness of history and realities that strive to foreclose the possibilities of dreaming.

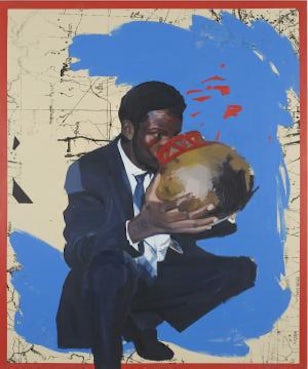

Over this elder’s right shoulder, a potted plant is shown again, alongside the image of a small boy holding a bottle. In Bira (2019), a man crouches, dressed in a dark blue suit shown drinking from a large container, his enlarged hand supporting its contents, the ritual beer brewed for the bira ceremony. He is placed foreground, on a canvas of wide vibrant blue brushstrokes, atop an enlarged, pre-independence Rhodesian map. The subject depicted is neither of Rhodesia, which is gone but remains named on the map and has impacted the land in ways that cannot be reversed, or fully integrated into the world of ancestors and traditional practices. He exists in a present constituted by different, conflicting, pasts and speaks to a time anterior to the settler-colonial project. In both Bira and Dreamcatcher, history is narrated not as a history of power or subjugation, rejecting both, but instead approached as a reality that can be made through social processes of participation that include collective dreaming and ritual practice.

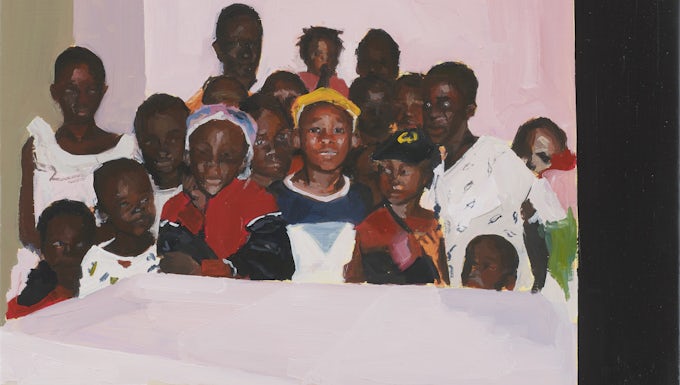

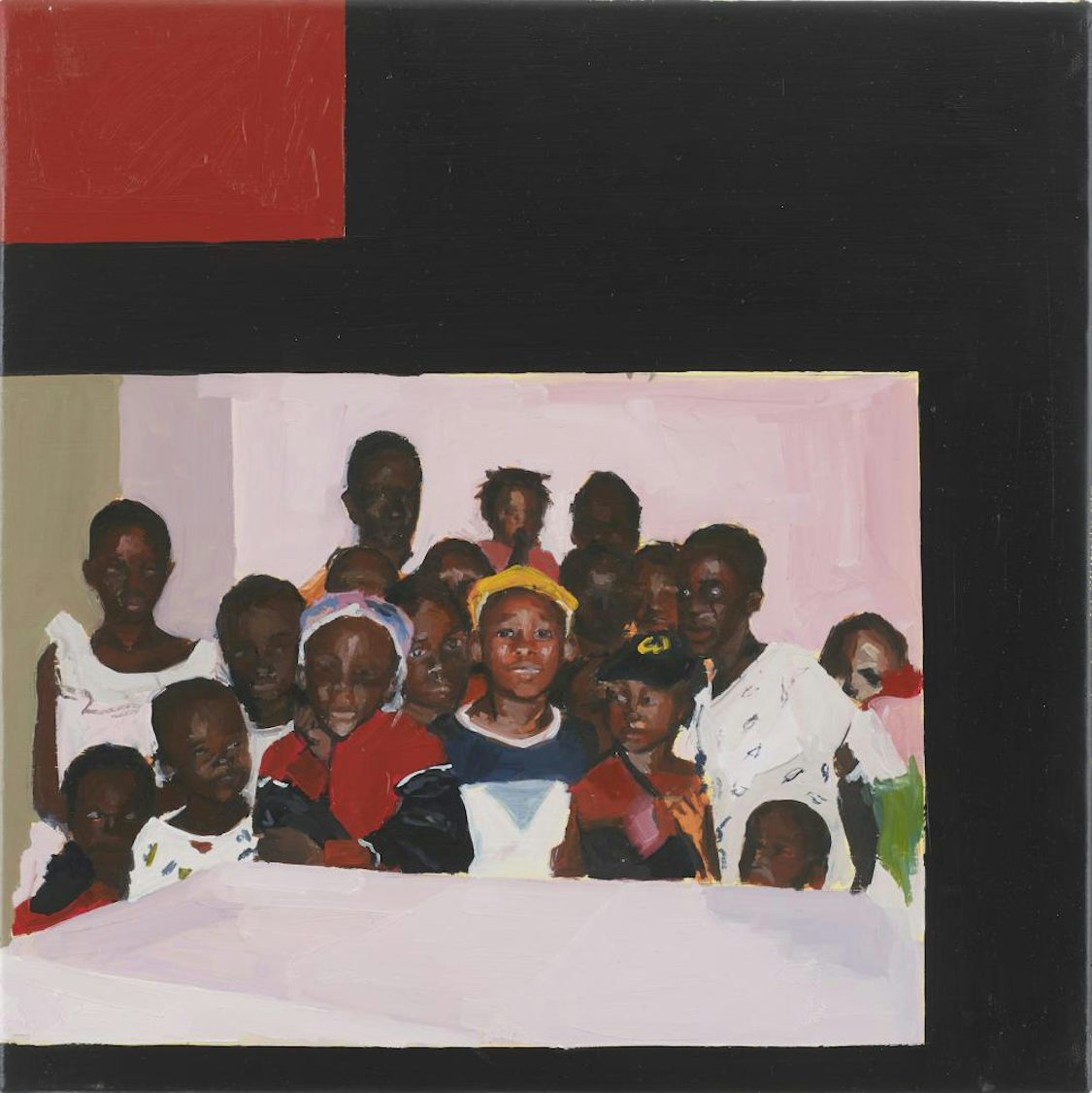

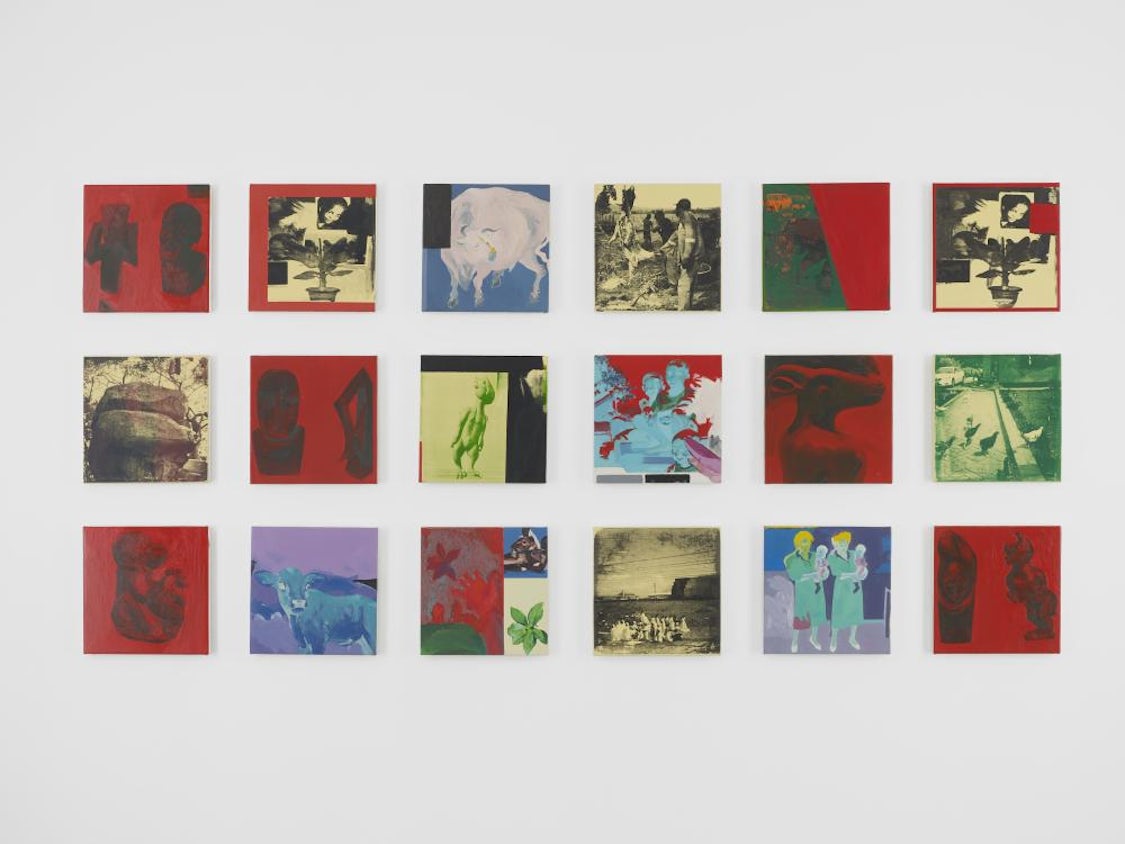

In the smaller room, small canvases presented as a series play with different ways of looking and modes of relationality. Displayed perpendicular to both Dreamcatcher and Shona Boy with Dove, these larger paintings repeat images in negative. Titled Speaking in Tongues (2019), this series addresses the construction of self and community in the digital domain and the particularities of the archive as both a physical and digital entity. Across these canvases are images of the famous stone formations of Zimbabwe, sandstone sculptures – abstract and figurative – church congregations, more plants, images from family archives painted in negative, and numerous references to livestock – live and after slaughter, from stylised illustrations. Nudes of two women together subtly introduce the question of queer life in Hwami’s imagining of home. Along with the paintings in negative, other canvases refer to analogue photography through consuming red hues that evoke safe lights and the emergence of the image through photochemical process. Questions are raised about the production, and reproduction, of images, of ideas. What does it take to make things real? From dreaming, to ritual, to painting, to photographic image-making, question of technique, technology and efficacy are repeated, bringing to mind the question of the legitimacy of these different technologies.

The title Speaking in Tongues is also an allusion to the question of legitimacy. It asks what is acceptable or permissible as proof when different world views come into contact. The stone sculptures, central to Shona material culture, can be read as an antithesis to the violence, erasures, and hypocrisy of the settler-colonial project. 10 They also speak to proof, proof of an ancient civilisation denied by the colonial imagination, even when presented in stone. Additionally, by using this title, Hwami puts a mode of communication belonging to the world of spirits, ancestors, and mediums into correspondence with the forms of digital communication and socialisation. In doing this, the series opens up our understanding of the non-local world, of closeness without proximity, both temporal and spatial.

Throughout the show, various temporalities not easily discernible from each other are mixed. The paintings reflect on the sense of being situated out of time when ones land has been settled, and on the rejection of linearity and the limits of the physical body in many non-Western world views. Often speaking of her work in relation to the history of Afrofuturism, what Hwami does in this show presents a plastic time, stretchable and prophetic, as well as a state of recomposition, at the heart of Afrofuturist thought. Hers is a time that accounts for multiple times: the now of Zhawi’s words, of ‘Flesh and Blood…’, and ‘Home is…’; the now of the exuberance of the Bira ceremony; the timelessness of mourning; the eternity of ancestors; the slow listening to elders and the fast pace of Instagram. Through her compositions, multiple pasts, futures, dreams, and documents are woven together, across generations and between the living and the dead, to retell home, not as place, but as a generative posture for temporal navigation.

Footnotes

-

Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, ‘(15,952km) via Trans-Sahara Hwy N1’, Gasworks, London, 19 September–15 December 2019.

-

Panashe Chigumadzi, These Bones Will Rise Again, La Vergne: The Indigo Press, 2018, p. 63

-

‘South X South East: Performance by Belinda Zhawi’ at Gasworks, London, 7 November 2019.

-

Mark Fisher, ‘The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology’, Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture, 5(2), 2013, pp. 42-55.

-

Tiona Nekkia McClodden, ‘TEXAS ISAIAH: TIONA NEKKIA MCCLODDEN ON TEXAS ISAIAH’, Artforum International, Summer 2018, available at https://www.artforum.com/print/201806/texas-isaiah-75535 (last accessed 16 April 2020).

-

Mbuya is the female form of Sekuru, meaning female elders, aunties, grandmothers or ancestresses in Shona.

-

Panashe Chigumadzi, These Bones Will Rise Again, La Vergne: The Indigo Press, 2018, p. 63

-

As told by the artist in ‘Interview with Kudzanai-Violet Hwami: (15,952km) via Trans-Sahara Hwy N1’ [online], available at https://vimeo.com/363574399 (last accessed on 11 February 2020).

-

Ashon Crawley,’I Dream Feeling, Otherwise’, ArtsEverywhere [online journal], 18 November 2016, available at https://artseverywhere.ca/2016/11/18/i-dream-feeling-otherwise/ (last accessed on 2 December 2019).

-

The country itself is named after the ancient structures of Great Zimbabwe or ‘great house of stone’, which the colonial regime denied could have been made by people of African origin, despite its location and insurmountable evidence