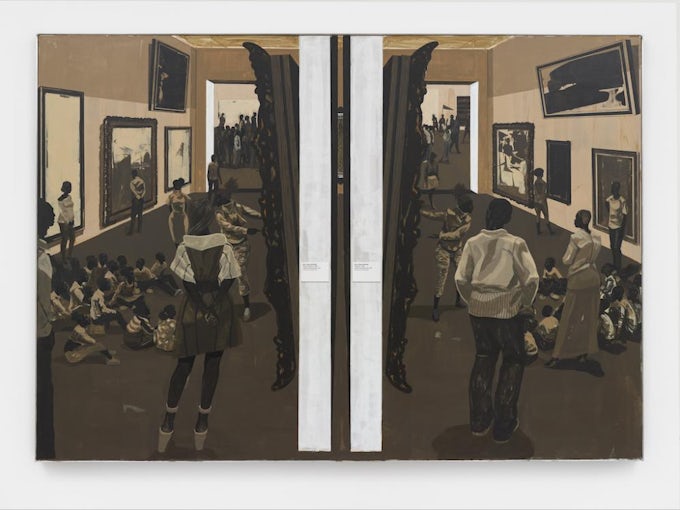

Inclusion is a good norm. The release of energies hitherto pent-up by exclusion lies behind the Afro-Atlantic transmutations performed by such artists as Lauren Halsey, Oscar Murillo and Paul Sepuya, to name a few – yet this cannot be a triumphalist story because the past decade also gave us a neoliberal racial formation that no longer even tries to clothe its violent antiblackness. Untitled (Underpainting, 2018) reveals Kerry James Marshall’s insight into such antinomy. In the mirroring spaces of a beaux-arts museum filled with black viewers, spliced between Barnett Newman zips featuring wall texts, the archival shell of Western art comes to house an energetic scene of civic assembly. The utopian feeling emanating from the scene’s unrealism has everything to do with the condition of unfinishedness, for what leaps out of the visual maze of symmetry and asymmetry is a sense of future possibility that questions the limits of the present. — KM

Over the past fifteen years, Kerry James Marshall has become the history painter of post-Civil Rights USA. In his large-scale canvases, figurative groups placed among scenic backdrops often evoke the utopian aspirations of the 1960s, and in this way his paintings open onto an imaginative or even fictional space in which the relation between past and present becomes the subject for a fresh set of narrative possibilities. Structured by the recombinant principle of collage and a painterly interest in the formal properties of flatness, Marshall’s body of work is best understood as a manifestation of Afro-modernism on account of its critical relationship to prevailing conventions of modernism. By examining his early work, my intention is to show how Marshall arrived at a set of choices that led him to an alternative to the discourse of postmodernism that prevailed at the beginning of his career in the 1980s, even as he maintained a complex relationship to the discourse of High Modernism that was associated with abstract painting and he views of critic Clement Greenberg.

Marshall’s enigmatic compositions, with their figures often in pairs or groups, suggest potential scenes of dramatic action, but any straightforward access to narrative content is intercepted by a rich ensemble of painterly effects in which various drips, dots, strokes and scumbles are scattered throughout the textured surfaces that are so distinctive to Marshall’s paintings. To the extent that such painterly ‘noise’ interferes with the figure/ground distinction as a foundational aspect of painting, it acts as the locus of conceptualisation in Marshall’s work, marking the point at which alternative understandings of ‘history’ are brought to the threshold of representation. By questioning the conditions of representation surrounding African-American history, Marshall’s concern with the 1960s parts company from the nostalgic treatment conveyed by a work such as Spike Lee’s 1992 film biography of Malcolm X. In addition to displacing documentary realism, Marshall also eschews the ironic handling of the 1960s that is expressed in the retro-kitsch aesthetics of Blaxploitation imagery. Rather, what Marshall achieved in his mid-1990s breakthrough, with paintings such as De Style (1993) and Lost Boys(1993), was a mode of historical reflection in which lived experiences of the past are invoked through a subtle poetics of allusion.

The Souvenir series (1997-98) touches upon the politics of the Civil Rights era directly, in the form of a background tapestry that depicts Martin Luther King, Jr. alongside John and Bobby Kennedy, above a motto that reads ‘We Mourn Our Loss’. But more often than not, Marshall alludes to the 1960s indirectly, such that a more diffuse sense of ‘pastness’ associated with childhood memories and the intimacy of family life takes precedence over the public sphere in which the tumultuous events of the period took place. In the Garden Projects series, works such as Better Homes Better Gardens (1994) or Untitled (Altgeld Gardens) (1995) convey a precise feel for the period in the shape of the mass housing projects that were built in the inner cities during the 1960s. Yet even as the distinction between public and private space on the canvas is literally blurred by splashes of paint – thus overriding the separation between the two realms, as well as interfering with the spatial separation of figure and ground – there is an affective charge of unsettlement, disturbance and violence that, I would argue, is conveyed by the way such painterly effects ‘deface’ the illusion of pictorial depth. Far from summoning history as though it were a given body of knowledge passively waiting to be depicted or narrated, it is the opacity of the ongoing relation between past and present that Marshall throws into the forefront of the viewer’s attention. In this way, the poetic interference activated by the disparate materials collaged onto the picture plane issues a break with the realism and naturalism associated with the genre of history painting in the modern West. But if we could accurately describe Marshall as a modernist whose work operates from an alternate methodology of collage, in which meaning is generated by the dialectical collision of heterogeneous elements, then we still face the question of how to describe exactly what kind of modernist Kerry James Marshall might be.