The appearance of two major exhibitions on Kathy Acker, now, feels both well-timed and untimely. It presents questions. How did it take so long? (The two shows, at Karlsruhe’s Badischer Kunstverein and London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, are the first such exhibitions, and appear more than twenty years after Acker’s death. 01) Or, since it has been such a long time coming: Why now? As the celebrity-driven reification of Acker’s persona recedes, the creative and critical necessity to articulate an active relation from Acker to the work of others and to history is becoming clearer. Her work opened up an experimental field that crossed literature, performance and visual art, and her own ability to read the world and to access the contingency of truth and representation via text is ultimately founded on a fugitive generosity and friendship rather than the mastery of any particular form.

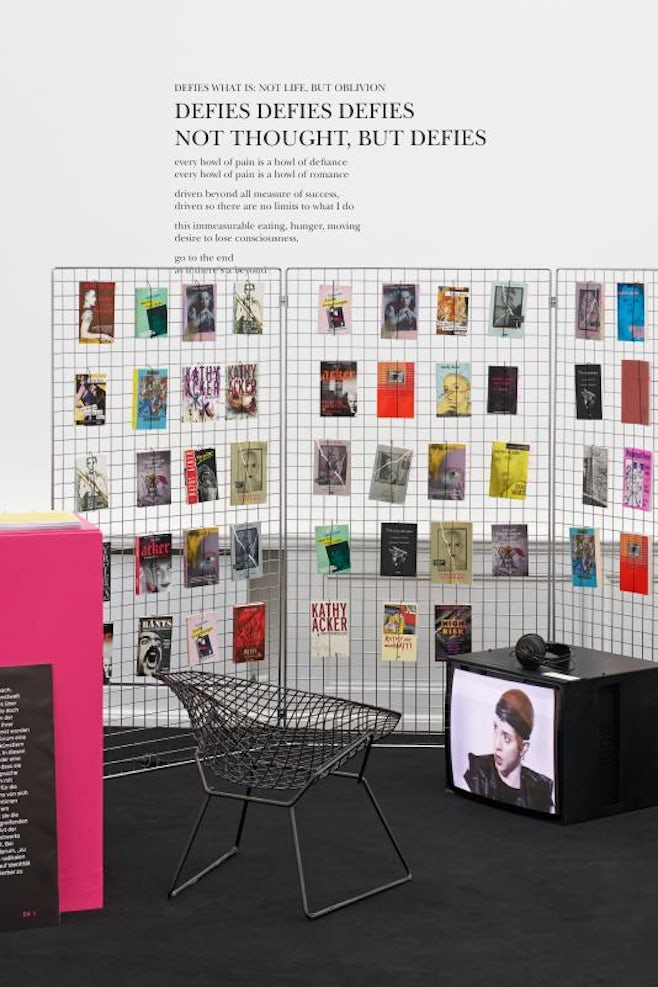

‘Kathy Acker. GET RID OF MEANING’, curated by Acker’s estate manager Matias Viegener and Anja Casser, director of Badischer Kunstverein, marks an important step in the collective re-reading of Kathy Acker – an ongoing process, and the result of the accumulated work of many people over the past decade or so. Rather than focussing on Acker’s explosive literary influence, the show emphasised Acker’s work as text, as performance, as process and as scholarship, while showcasing works by artists who were influences on or influenced by Acker. Avoiding themes in favour of a more chronological-historical flow, the exhibition was structured around four key texts that correspond to major conceptual movements in Acker’s work. The Childlike Life of The Black Tarantula (1973) and Blood and Guts in High School (1970s/1984) were here associated with investigations of identity and subjectivity; In Memoriam to Identity (1980) proposed a ‘deconstructive’ phase, which I would associate more with reading, coding and passing; and her last work, Pussy King of The Pirates, reflected Acker’s late turn away from her role as celebrated writer, towards the mythological and a theatrical approach echoing an earlier relationship to performance. Limiting the curation to just these four works was a wise constraint in a show that spilled out of its bounds at every opportunity. The exhibition design by Fotini Lazaridou-Hatzigoga repurposed the gallery’s old vitrines and plinths for the show, painting them black and resting them on raw planks painted hot pink. The effect was surprisingly austere, a late nineties post-riot grrl po-mo flex in museum-drag.

The idea of Acker’s work as ‘art’ rather than ‘literature’ – as an interface of conceptual, performative and linguistic experimentation – comes into immediate focus with her early work The Childlike Life of The Black Tarantula. This was ultimately published as a book, but began in the early 1970s as a serial narrative mailed out to ‘subscribers’, mainly artists and poets selected by Acker. Presented in the first part of ‘Get Rid of Meaning’ alongside documentation of performances by Eleanor Antin and Lynn Hershman Leeson, whose work with assumed identities and personas informed Black Tarantula, we see Acker’s emergence via the fertile crossings of 1970s art scenes in New York and California. Acker wrote longhand into square notebooks cutting, appropriating, or – her preferred term – pirating from the texts of others. An entire Black Tarantula notebook is displayed high and grid-like across two walls. Above it appears the legend from Acker’s anti-business cards from the time: YOU ARE NOW AN ENEMY OF THE BLACK TARANTULA.

Black Tarantula was sent out under a pseudonym, and Acker’s own image, which would later become so publicly entwined with her work, has not yet entered the show. In its place, perhaps, a large plush spider sits on top of one vitrine, not announced or labelled as the artist’s (though it is), activating the texts with the vibrating liveness of an occupied web. A spider logic seems coded in handwritten pages, showing Acker’s gridded keys to the sentence structure of her cut ups, mapped out in symbols and diagrams. She takes the old modes of study from the classics, transcription and translation by key, and turns it into a generative method. In a state of bibliomania as intense as this, bibliomancy is the only suitable approach.

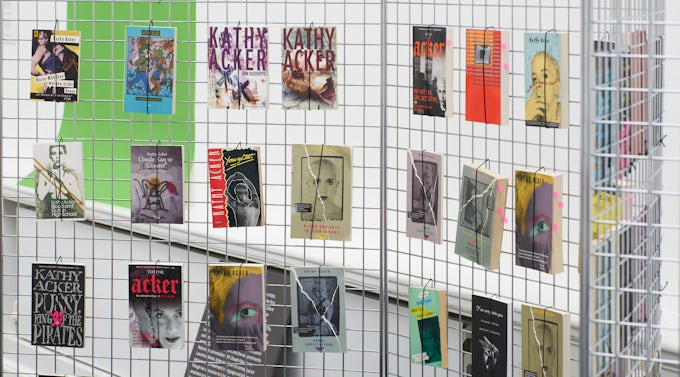

Acker’s repetition, rewriting and revisions, established here clearly in the treatment of her handwritten pages, recur across displays; the different works transcribe each other, mutating with each iteration. The challenge of navigating an exhibition containing such a density of text is immediately apparent – the linearity of reading is necessary but also constantly disrupted. Vitrines contain hand-written letters alongside typed missives and mailouts; her books are bound to the black plinths, opening to the reader; and in her notebooks, text spirals and repeats in devotional or magical diagrams. A reading area features the many translated editions of Acker’s works, with a photocopier and an encouragement to copy at will. Lineage is piracy, piracy is friendship: I learnt this reading Pussy…, my first favourite of Acker’s books. Citation is the text, and writing gives way to reading. We don’t have to lay claim to anything.

The show’s verbal density often also gives way to more visual and visceral moments – again, echoing the logics of so many Acker texts. The large Blood and Guts in High School room opens out from a monumental abstract digital print by Anja Kirschner, its lime green, tv-static grey, pink and black recalling Acker’s book covers from the eighties onwards; and to the left, on the wall closest to hand is an enormous blow up wall print of the hand-drawn dream maps from Blood and Guts in High School. The book was banned for years in Germany due to its perceived obscenity. Turning into the room to orientate myself I am faced with a wall of books. Like the tarantula it takes me a while to work out they were Acker’s but I know it in my body before I articulate the thought. I know because, and I didn’t expect this, I am crying. The selection of her books was curated by research assistant Daniel Shulz, with Casser, from Acker’s personal library, which is housed at the University of Cologne as the Acker Reading room. Standing there reading the spines of her books feels like looking at the roots of a great tree from beneath the earth.

Acker’s performative use of media and publicity as a means of destabilising or reformulating identity is highlighted by two videos, filmed years apart, shown in the section In Memoriam to Identity. In the first a thirtysomething Acker looks like a Vivienne Westwood Peter Pan; in the second she’s got grey stubble in her buzzcut and her face has gained the gravity of age and illness. Alongside these are Kaucilya Brooks’ photographs of items from Acker’s wardrobe, portraits by Del La Grace Volcano and many others, and still images of Lil Picard’s performance with Acker, Tasting and Spitting (1975). The photographs don’t carry anywhere near the charge of the handwritten/hand-drawn artefacts, nor that of the cuddly tarantula or the videos. But as documents of a practice, like those of Antin’s and Hershman Leeson’s in the first room, their presence here is entirely necessary. Acker’s iconic presentation of herself was often interpreted, particularly in the popular press during her time living in the UK, as a narcissistic demand for attention. Low in the mix here, her raiment seems more like a means to something than an end, to be worn rather than shown. It’s less like costume and more like dazzle camouflage, or mis-directional armour. Disguise in plain sight. Her wild look may be understood as functional, an interface that allowed her to perform the work.

Acker’s late, and sadly abruptly truncated, turn towards a more theatrical mode shows how she was moving into something like a dramaturgical process, a more collaborative and enlarged relation to art-making, incorporating and exceeding her previous roles as writer and performer. Acker’s maps for Pussy King of The Pirates appear alongside an audio recording of the performance version of Pussy…, staged with art-punk legends the Mekons in the late 1990s. This space leads into a dark space with Carolee Schneeman’s classic film Fuses (1967) – the artist fucking her lover with her cat looking on – framing the tender alienation of Acker’s Blue Tape (1974), an early video experiment with Alan Sondheim, the artists fucking and describing the experience in relation to their practices. The whole room flickers, and there’s a sense of looping back, or time travel: Pussy is separated from the Blue Tape and Fuses by decades yet they share much, not least a kind of optimism. It’s a sweet and understated goodbye to Acker, dwelling on the joy she took in her body rather than the sadness of her passing.

‘GET RID OF MEANING’ refuses, as Acker did, the temptation to sever history from the present. The single film in the final room, I Want (2015) by Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz, speaks to this condition. Sharon Hayes performs a monologue in which Chelsea Manning’s words and narrative are pirated and mixed with Acker’s. Enacting the continuing richness found by those working with Acker’s texts as material and the power of her methods, the story of Acker is spliced into that of Manning, tracking connections between Acker’s work and Manning’s activism – emphasising the demands made by Acker for the emancipation of text and information from the strictures of property relations and other oppressive power structures. Between text as code and the politics of information, the show’s closing is an opening to a speculative now.

Footnotes

-

‘Kathy Acker: GET RID OF MEANING’, 5 October–2 December 2018, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe was the first comprehensive solo exhibition of Acker and included a three-day symposium on her work; see http://www.badischer-kunstverein.de/index.php?Direction=Programm&list=Vorschau&Detail=724. ‘I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker’, Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, 1 May–4 August 2019 is the first UK exhibition dedicated to Acker and her written, spoken and performed work; see https://www.ica.art/media/01518.pdf.