It is self-evident that nothing concerning art is itself evident anymore, not its inner life, not its relation to the world, not even its right to exist.

-Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory

Roger M. Buergel, artistic director of documenta 12, has done what no one else has yet realised on such a scale: he has returned to the bombed Kassel, left in ruins (the polis) and devastation (the human species01) following World War II, and investigated the foundations of an art exhibition that was unexpectedly successful in its first edition in 1955. No statement of his has been published in the exhibition catalogue – a guide published along with a ‘picture book’ – and everything leads us to believe that he is not a curator who wishes to become known for the discourse accompanying his exhibition.02 One assumes that, for him, words obstruct the visibility of art. This is obvious in the preface to the exhibition catalogue, numbering around three pages, which denies any hope for the establishment of a ‘new’ theory of art: ‘The big exhibition has no form.’03This is a humorous statement when you consider that it was being used to describe one of the most controlled exhibitions of recent times. No show of such scope escapes mistakes during the journey, unforeseen accidents in the plan. Nevertheless, what seems the result of uncertainties instead becomes a challenge for the future which will be recognised in due time. Documenta 12 presented itself as the ‘most important exhibition of contemporary art in the world’, a slogan that the international press willingly adopted; it has been compared to Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920), known as ‘the angel of history’ by the Benjaminians. To sum up, the hyperbolic way in which it has been produced has also contaminated the majority of critical reactions to it.

As one went up the staircase of the Fridericianum museum, Klee’s angel hung from the wall, discreetly watching the past with its wings wide open. Discreetly, because this image circulates between the scholars of the philosophy of history, where the present is merely transient. There it was, in that impromptu alcove – a passageway, one could say – though already established in the future for which it has been designated, sneering at Walter Benjamin’s concept of hic et nunc! As the original work wasn’t made available for the event, the Angelus Novusappeared only as a copy – yet without seriously limiting the visitor’s appreciation, given that the age of technical reproduction made the age of the nonchalant journeys through the corridors of the most visited museums possible. It is, however, more difficult to find in documenta 12 the paintingL’exposition universelle (1867) by Edouard Manet: it is in a display case, for those who head towards the bathroom of the Neue Galerie, almost excluded from the exhibition – like the Universal Exhibition in fact did twice with Manet. This time, copy by copy, Buergel, who worked with curator Ruth Noack, became even more radical, opting for the postcard reproduction.

If there is one ingredient that the pair does not lack, it is an enlightened humour, full of references to the past and future. The narrative of the ‘migration of form’ at work in the city of Kassel, the first in Europe to have a public museum of art, originated in miniature paintings of Eastern empires which no longer exist (the Persian and the Ottoman) and within the exhibition it moved from calligraphic gouaches from the Islamic world – drawing on influences from India, Iran and Europe – to Central Asian rugs and embroidery from the fourteenth to nineteenth centuries. Some of these allusions appeared to have been taken from Palestinian photographer Ahlam Shibli’s photos of Bedouins; others focused, for example, on the symbol of a swastika in the grooves of the Qing Dynasty’s Chinese chairs (1644-1911). But it is difficult to separate humanism from a Eurocentrism at this time of a ‘war on terror’. We were being taken by the hand, being made to look at the exhibition as if we were art students. Not by chance, education was one of the curatorial threads of the exhibition, together with modernity and bare life. As an ‘integral element of the curatorial composition’, education was understood to be different from the educational programme – in other words, different from the guided visits to the public.04 How did documenta 12 reflect the concept of bare life? This issue is yet to result in theoreticians splashing a lot more ink, drawing on writers from Benjamin to Giorgio Agamben, all perplexed because art is not the immediate medium through which one can understand the meaning, in our modern life, of camps or bio-power. However, the question ‘What is to be done?’, together with the debate on education, showed a will to define this bare life using a more ambitious process than a service provided by the mediators; it suggested a desire to take the question of Bildung (‘education’; above all, aesthetic) to the widest possible forum.

According to this exhibition logic, pregnant with a deep historical awareness, Buergel’s project plunged into the origins of documenta in search of what still touches (us) in the present day. Louise Lawler’s photographs seemed tailor-made for this project, because of their inherently modern qualities. They were reminiscent of the beauty of alien works that, in a certain way, ended up giving a new meaning to the appropriation of the Manet piece, as if it were only on the fringe of the complex web of internal theoretical dialogues. But Lawler was also there to contribute to the rhythm of the display. Like her, the majority of artists were not given single rooms in which all their work was grouped together; instead, they found their work spread throughout various exhibition spaces. The white cube was rejected and replaced, without feeling guilty for betraying Modernism, by coloured spaces, woven curtains (both loose and tied back) and low lights, reminiscent of the bourgeois salons in the Fridericianum and the Neue Galerie.

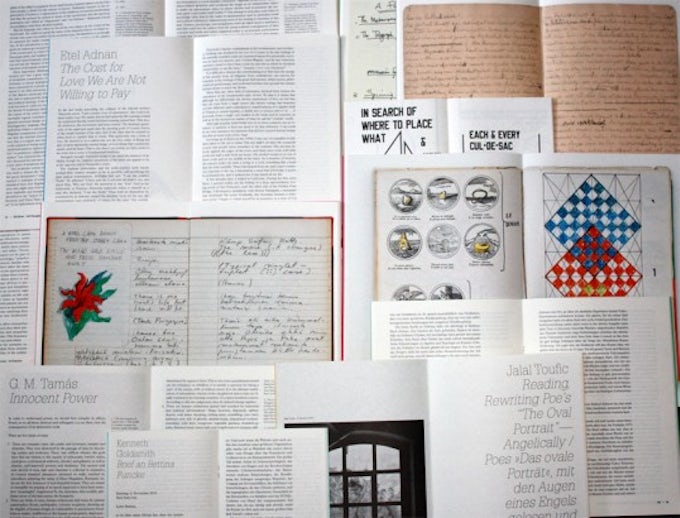

This bright excitement generated by the display cannot be found in the catalogue, with its carefully conceived, minimalist layout of images. This is an interesting point, because in no way could the reception of the work be the same as its inventorising. A positive step for curatorial language? There was no common identity for the exhibition and the publishing project – another unfulfilled expectation. Two official versions of the same documenta exist, which are symmetrically opposed in aesthetic terms: what the exhibition space wanted to confirm, and what the publications can offer whilst being a separate and autonomous support to the exhibition.05 The publication, which claims the status of catalogue, is no more than a guide: it has nearly 400 pages, with a short text for every double-page spread, written in a colloquial style and presented in both English and German. What happens is that, despite this reversal of importance (a guide as a general catalogue), the entries follow a chronological order, and there is no identification of the artist’s place of origin (nor is there on the labels within the exhibition). Within the exhibition space, the period when the work was made was mentioned in very rare occasions. It seemed like the curators imagined a visitor cleansed of any knowledge that could serve him or her to immediately determine the work, even before getting the chance to venerate it. A ‘neutral’ visitor, one could say – a visitor who has never seen an exhibition. But that is difficult to find: it is like asking a painter to paint a rose, whilst forgetting all the roses ever painted while he does it. A lesson from the mature Matisse: ‘The first step in the direction towards creation is to see each thing in its own truth…’.06But are we not creatures with saturated visual memories?

*

In documenta 12, architecture became the ideal stage for the juxtaposition of gestures and spatial movements coming from totally different cultures and periods. This orchestration culminated on the top floor of the Fridericianum, where the height of Ai Wei Wei’s chairs (one of the most interesting works in the show) obliged us to twist our necks in order to see Hito Steyerl’s film Lovely Andrea(2007), whose subtitles were blocked by a rail when the visitors were seated. Not only did we become part of the video installation, which documented the tradition of tying up and hanging young Japanese girls by ropes (kinbaku, an artistic/erotic practice) – we are also able to simultaneously see one of Trisha Brown’s choreographic works, in which dancers are wrapped up in clothes and ropes. To complete the show, a gigantic installation by Iole de Freitas of lines and transparent surfaces undulated through the space, enhancing expression through form. Subsequent visits to the Fridericianum confirmed a growing mal-être: from Mira Schendel’s Droguinhas (‘little nothings’) (1966) to the ‘spider woman’ of Lovely Andrea, passing through the pathetic filmed choreography of Luis Jacob, modernity was treated by way of elementary analogies.

Buergel’s biggest ‘provocation’ was the Aue Pavillon, a twelve-thousand square metre structure built especially for documenta 12. The building itself, discussed at length by the general press, was a contentious issue for the curators and the architects, Lacaton & Vassal (who withdrew from the project), as well as for the local inhabitants of Kassel. It is symptomatically the space in which the curatorial control lost its accuracy, as it was the only contemporary construction in which the curators did not put into play their mise-en-scene; it was also the place in which the educational element was reduced to individual artworks, hoping to elicit ‘relational’ behaviour from the public. As an example were two big white panels, each situated at the entrance and the back of the pavilion; visitors were allowed to press a button on the first one, which made a sound that was heard from the other panel. With this piece, Andrei Monastyrski wanted to prolong the present in two moments – an intention that lost all its nuances of silence and distance from the moment that two children (or two adults) grasped the mechanism and kept their fingers on the device.

Within the Aue Pavillon, the project that perhaps best represented the curatorial ambition was Mladen Stilinovic’s The Exploitation of the Dead (1984-90), a box the size of a small house, with windows and a door. Inside and outside, from top to bottom, dozens of small objects were placed on the walls – such copies of Suprematist paintings, collages and photographs. Nothing was what it seems – there were even real cakes with cream, replaced frequently so they would remain fresh. How can one understand this collection of symbols, displayed next to the image of one man (Kasimir Malevich) on his deathbed? What is the meaning of placing such an image at the top of the doorway? One hopes that a work with so many references (it was practically a three-dimensional book about the history of modern art, overflowing with signs) manages to reach out to the public, and be approached without any clear identification method. Yet, what is this artwork, if one is not capable of reading a cross and black square? What revelation is possible if we no longer belong to this past?

The journey to the Wilhelmshoehe castle added a sense of nostalgia to documenta 12: both the magnificent collection of paintings, and the hilly park and its ruins (among which Allan Sekula’s photographs appeared after a vigorous walk), were part of the curatorial project. Such effort belonged to the realm of merit. Buergel and Noack were aware of this, as they expanded the limits of the enjoyable contemporary exhibition, making it instead an almost Rousseau-esque experience which re-established the battle between the sublime of nature and the sublime of art. This extemporary scene, situated nearly half an hour from the centre of Kassel, is the enterprise’s most risky moment – it is the place in which the past speaks louder than the present. This was the moment for those who reject contemporary art: the Old Masters, the timeless classics, guarantee a much more sensual impact than Dias and Riedweg’s folklorisation of an anthropophagic ritual in Funk Staden (2007). It is incomprehensible that both Schendel’s Droguinhas and books are articulated around Montesquieu’s question ‘How can we be Persians?’, rather than qualifying the status of the modern imperative. Schendel’s investigation tackled the origins of writing and architecture from the 1960s onwards, just as the transparency (of rice paper and acrylic) was her attempt to make presence and representation merge. In the castle a gouache titled A Woman Spinning (c.1820) was placed next to a line-drawing; the Modernist dream continues to be challenged in this way, and at these heights the curators used Hokusai and Nasreen Mohamedi to say the same thing.

Without being feminist, the show brought back the names of women whose reputation was in the process of being delegated to a secondary level: Schendel, Grete Stern, Atsuko Tanaka, Bela Kolarova, Graciela Carnevale, Lee Lozano, Nasreen Mohamedi, Lotty Rosenfeld, as well some others whose talent is a curatorial overstatement. The main figures, however, were still men: Peter Friedl, John McCracken, Kerry James Marshall, Juan Davila and James Coleman. In the category of historical collectives, Tucuman Arde was not swallowed by the coloured walls, and they continue to be not only resistant to museum institutionalisation, but also an archive waiting to be discovered. It is worth noting that the Latin American continent was perhaps the least benefited, despite the presence of artists such as Schendel, Luis Sacilotto and Leon Ferrari. Sacilotto, an artist who left a body of work comparable to only a few others, was represented by a single, and relatively small iron sculpture. His history among the Constructivists has been erased; his work was used by the curators just to give a hint of Constructivist geometry in relation to adjacent African masks.

Whether you liked or disliked the artworks included, Buergel and Noack had a project. Yet although it emerged from a relationship with discourse, the project was unable to free itself from the problem of making the artworks into puppets at the service of a foreign objective. Documenta 12 should be remembered every time a curator wants to withdraw a work from its original context. The characterisation of modernity as an ‘unfinished project, which asks to be moulded and interpreted’07 led to a necessary return to the repressed, a will to form after years of experimental practice, which was seen as suspicious for having voided the process of meaning. Buergel made his own mark with a show that indirectly celebrated the reconstruction of Western Germany by reopening the wound of the separation between Eastern and Western Europe – and complicating that modernity. Nedko Solakov’s archive, Top Secret (1989), is one of the moments where this happened, by placing us in between fiction and history – uncovering an ambiguous biography about the secret regime in Bulgaria. We were still in the Neue Gallery, where we found drawings by Peter Friedl, made in 1968 when he was just eight years old. It was one of the few instances in the exhibition when a caption accompanied the work. The anonymous origin of the art was at stake, and Buergel is supported here by the unresolved myth of Picasso. It was another way of evoking the spirit of the first Documenta, after so many other exhibitions based on Beuys and Broodthaers. However, next to this room was another in which drawings by Solakov were displayed in a sequence. Their formal resemblance to sketches, a point also made by Friedl’s work, detracted from their potential conceptual appearance. Here the formal juxtaposition had more presence than the concept, and played into the character of documenta 12; in other words, into the indistinction between art and the construction of a myth. In the catalogue, the curator remembers that Picasso helped us see the world like a child; Matisse, who was arguably closer to artistic emotion than artistic theory, was also known to have said that, ‘It is necessary to look at all life like one did as a child; and losing this ability does away with the ability to express oneself in an original way, that is, in a personal way.’08

Angelus Novus could have been discussed in the Modernity issue of documenta 12 Magazine, if documenta 12’s ambition hadn’t been to be known as the documenta-of-all-documentas, a meta-documenta. The ‘big’ painting, at the end, was the small Gerhard Richter that dominated the network of articulations. Betty (1988), somewhere between a portrait and a still life, shows a reclined girl, seen only from the neck upwards, with her faced turned towards the visitors. One is aware that the child is also an image of the angel. Inspired by a photograph of the artist’s daughter, half of her face remains in the shade, leaving just one eye wide open at the centre of the painting. Kaja Silverman wrote that there is no way of resisting the desire to meet this gaze, but that, in order to do so, we twist our necks to the side, offering them to the guillotine.09Benjamin knew that there is no contemplation without horror: ‘There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.’10 No one doubts that Buergel knows exactly how much bare life there is concentrated in a child.

Translated by Miriam Metliss

– Lisette Lagnado

Footnotes

-

The Human Species is the title of a book by Robert Antelme published in 1947. The three recurring themes in Roger Buergel’s ‘work’ – modernity, bare life and education – approach transversally a silence Antelme identified in his book-memoir of 1947, when he discussed the gap between lived experience and the possibility of narrative inside a concentration camp (Buchenwald).

-

What I call ‘curatorial statement’ is a text that was published before the opening of documenta. See Roger M. Buergel, ‘The Origins’, Modernity?, documenta 12 Magazine, Issue 1, Cologne: Taschen, pp.13-27. In ‘Documenta 7: A History’ (1982), Rudi Fuchs also had an impetus to recover the modern.

-

See documenta 12 Catalogue, Cologne: Taschen, 2007, p.11.

-

See Modernity?, documenta 12 Magazine, op. cit., p.219.

-

The biggest success of documenta 12 was the editorial project, coordinated by Georg Schoellhammer. After several research trips, like curators looking for artists, a team of editors invited almost 100 magazines to answer the three questions of documenta 12 (modernity, bare life, education). The most interesting part of this project was the dynamics established during the 100 days of the exhibition, in which editors were invited to take part in informal and quick discussions, workshops without an academic inclination and without the obligation to solve problems or issues.

-

Quoted by Regine Pernoud, Le Courrier de l’UNESCO, vol.6 no.10, October 1953, in Henri Matisse, Ecrits et propots sur l’art, Paris: Hermann, 1972, pp.321-23.

-

See documenta 12 Catalogue, op. cit., p.219.

-

See H. Matisse, op. cit.

-

See documenta 12 Catalogue, op. cit., p.104.

-

Walter Benjamin, ‘On the Concept of History’, Gesammelten Schriften, I:2, Suhrkamp Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, 1974.