In Cold Cuts, at the Espai d’art in Castelló, Spain, the California Conceptualist John Knight addresses the history of illegal American interventions since the 1950s. The show is articulated in the design-inflected, self-critical language that Knight has been developing since the late 1960s, when he turned from Minimalism and Conceptualism to work that specifically challenged the art system and its conditions. Since that point Knight’s practice has connected to a materialist tradition that has been lost for a long time in the United States, in which social critique is closely linked to the artist’s desire to transform the artwork’s modes of production and distribution. In his recent exhibition, curated by Michele Lachowsky and Joel Benzakin, Knight produced an installation in the Espai galleries and an artist’s book published for the occasion, whose instructions are oriented beyond the temporal and spatial confines of the show.

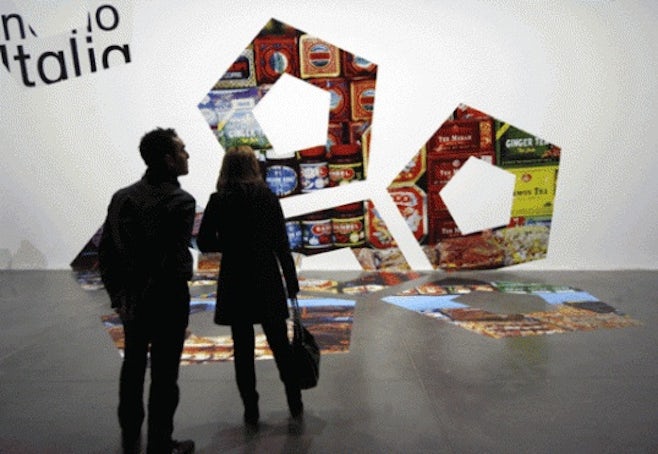

The installation occupies the Espai in the form of a two-dimensional, apparently decorative pattern of large, colourful vinyl pentagons affixed to the floor and walls. The images and texts in these shapes reveal the central motif of the exhibition: the relationships between gastronomy, exoticism and US imperialism. Images of traditional recipes from countries such as Vietnam or El Salvador, press photographs from political events (such as the assault on the Palacio de la Moneda in Santiago, Chile in 1973) and texts referring to the activities of the US secret intelligence services 1950, on the one hand, denounce the US interventions into the internal politics of these states, and, on the other, point to the effects that these interventions have had in terms of dismantling and altering local cultures.

In a succinct metaphor, the vinyl network of pentagons alludes to the ‘layers’ that hide underneath the anodyne and hermetic appearance of the Pentagon building in Washington, DC. Like the cold cuts from the exhibition title, these decals are layered all along the exhibition space, suggesting the repressed history of US foreign policy.

Knight’s message is clear. It exposes the discomfort – and, to some extent, the guilt – that many US citizens experience in relation to their country’s history. What makes this intervention different from other projects with similar intentions is its dialectical approach – the methodological inversion that the artist effects between the roles of exhibition and catalogue. Since the conventional function of the catalogue is to document or publicise the exhibition, here the reverse is this case: the exhibition functions as an advertisement for the publication. Cold Cuts is thus divided into two acts. The ‘first act’ is the display that occupies the exhibition spaces, which evokes a feeling of immediacy through a strategy of ‘over-design’ – a ‘vulgar’, unsophisticated appearance, similar to the one that can be found in sales conventions. These two elements, design and vulgarity, are a constant in Knight’s work: design was key to installation projects such as Journals (1978), JK(1982), Museotypes (1983) or Federal Style (1989).01Vulgarity, as T.J. Clark has noted, is a constant in North American contemporary art – from Jackson Pollock’s paintings to Dan Flavin’s light sculptures and Dan Graham’s lists.02This tradition adopts the most prosaic elements of daily life (and the type of design Knight adopt qualifies as such) as its main material.

For Knight, who has often focused his work on the effects of the transition from an industrial society to a service-based one, the appropriation of design also identifies a language that increases the appeal of commodities. Here, precisely through the conspicuousness of the exhibition’s design, Knight questions many of the conventions that shape the production, exhibition and distribution of artworks today. He formulates an attack on his government by quoting the style of design employed by the capitalist system that the US government defends and promotes: the instrument that is used to expand the capitalist society is turned against it.03 Secondly, the exaggerated use of design makes the exhibition paradoxical, as the accessibility that results from the design strategies contravenes conventional modes of contemporary art installation. By thus aping the language of advertising, Cold Cuts introduces the only object Knight is interested in – the ‘second act’ of the exhibition: a recipe book whose chapters, titled after US military operations in different countries since the 1950s (such as Ninotchka, Ajax, Success, White Star or Voodoo), offer cooking instructions for traditional dishes from those countries. The recipes appear in the book accompanied by quotations by US politicians justifying their government’s actions, as well as images documenting those actions. Out of the series of quotes by Senator Joseph McCarthy, President Harry S. Truman, George Marshall, John Foster Dulles or Henry Kissinger, one of the most interesting is one by President George H.W. Bush in the context of the invasion of Panama in 1989, which reads, ‘Our lifestyle is not up for negotiation’.04 By means of his recipes, Knight proves its corollary, that the American lifestyle is just one among many.

The sensuality or tactility suggested by the reference to gastronomy reinforces the relation that Cold Cuts establishes between design, publication and ‘use value’ implicit in the work. Because of that, in a clear dialectical opposition to culture as merely visual (a predominant conception within Western culture thanks to the development of audiovisual technologies), Cold Cuts alludes to a mode of creating relations between people through reading or food – a mode that is on the opposite side of the spectrum from the ‘distance’ proposed by traditions based on the gaze. These traditions are based on contested values such as private property, the protection of individual spaces, the accumulation of goods and speculation on the value of the artwork. But against the immediacy of the gaze and against the adoption of these mechanisms by the market economy, Knight proposes, in a symbolic mode, the slowness of a ‘good meal’, meaning as something deferred, as well as a definition of culture and creativity based on alternative values such as ‘use’, the collective and the popular.05 These values bear reference to the magazines, plates, posters, carpets or flowerpots through which he has in the past investigated the space in between art and non-art.

Knight’s critique, then, takes to its extreme the logic of advertising and design, mercilessly deconstructing them in order to question the fetishism of commodities, illuminate the structures that produce them and trouble the notion of artwork as a perfect producer of plus-value, but also in order to offer alternative models. These models relate to the artwork as a public good, within the exhibition space – here conceived as a muralist hybrid between image and architecture – and also within the publication mode effected by the artist’s book. For Knight, our lifestyle can – and must – be negotiated. (And this also applies to the conditions of production, exhibition and distribution of artworks.) As Anne Rorimer has said, ‘works by Knight self-referentially comment on their place in the culture. At the same time, they illuminate aspects of the given social system, with which they are visibly and thematically united’.06

Knight’s work refuses to be ‘consumed’ by the predatory gaze of capitalism, or by the abstract spaces of the ‘art’ institution. It projects itself onto time, and crosses the limits of the exhibition onto the act of reading – and of cooking, even. In this way, his project becomes a sophisticated device that, by expanding its reception to experience and memory, increases its ability to produce meanings or associations for the viewer. Knight’s work is, as a Spanish phrase says, ‘a loose verse’ – an element that belongs to the system but doesn’t quite fit in.

– Pedro de Llano

Footnotes

-

The dialectic between art and design can be traced back in American art to Clement Greenberg’s warning to painters not to go beyond the edges of the canvas, in order to stay away from the ‘mechanical’ look of sculptural objects. The tendency to actually do so, with the intention to question the autonomy of art as defined by high modernism, has its origin in the 1930s, and peaked between World War II and the beginning of the Cold War. See Clement Greenberg, ‘Our Period Style’, Clement Greenberg: Collected Essays and Criticism, ed. John O’Brian, University of Chicago Press, 1986, vol. 2, pp.322-26.

-

‘If the formula were not so mechanical, I would say that Abstract Expressionism painting is best when it is most vulgar, because it is then that it grasps most fully the conditions of representation – the technical and social conditions – of its historical moment.’ T. J. Clark, ‘In Defense of Abstract Expressionism’, Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999, p.401.

-

It is also interesting to point out that the pentagonal structures employed by Knight refers to the tradition of modernist painting: they recall Kenneth Noland’s and Frank Stella’s paintings, alluding at the same time to the capitalist system hidden underneath the apparent neutrality of their geometrical shapes.

-

George H. W. Bush, cited in Cold Cuts, Espai d’art contemporani de Castelló, 2008, p.124.

-

With ‘use value’ I am referring to Knight’s specific interpretation of this term, which is related to the symbolic. It refers to a questioning of the superstructure in which objects are inscribed in order to form part of a wider social, political and economic context. This distinguishes Knight from artists from posterior generations, such as Jorge Pardo, who explore much more ‘real’ applications of their objects. Knight considers Pardo’s work to show less reluctance to the system where his work operates. [Ref?] See Knight’s conversation with Isabelle Graw and Benjamin H. Buchloh, ‘Who’s Afraid of JK?’, Texte zur Kunst, no.59, September 2005.

-

Anne Rorimer, ‘John Knight: Designating the Site’ (exh. cat.), Villeurbanne and Rotterdam: Le Nouveau Musée and Witte de With, 1990, p.25.