Bill Burns’s exhibition of The Flora and Fauna Information Service, 0.800.0Fauna0Flora (2008) and Bird Radio (2007-2008), at the ICA in London in 2008, put a full supply of nature rescue gear on display. From January to February earlier this year, visitors to the Institute’s digital studio could investigate the varied contents of Burns’s Safety Gear for Small Animals, the ‘largest museum of safety gear for small animals in the world’. The mini-museum contains: miniature hard hats, high-visibility vests and safety visors designed for protective animal wear; a ‘proving machine’ for testing the durability of safety gear; a hydroponics kit for growing Alliumplants from Mesopotamia; and the ‘Boiler Suits for Primates Kit’, a suitcase outfitted with miniature versions of flip-flops and other provisions received by prisoners at Guantanamo Bay. The arsenal of equipment, rendered in eerievraisemblance to its human-scale variety, addressed the question of how to counteract the threats to nonhuman and human natures alike, and reminded audiences of the environmental and political threat in which animals, plants and people are perpetually caught.

Burns is the director of Safety Gear for Small Animals, a Canadian-based organisation that has travelled to various museums and galleries with its fastidiously assembled models. Executed in reduced scale – for an animal approximately the size of a marmot – the mock-ups bring the issue of protection from environmental threat into high relief, reflecting the apparent incommensurability to the task at hand. With deadpan precision, the organisation looks at the climate of risk that affects animals as well as human beings. Their safety gear and rescue manuals are as much conceptual projects as they are multimedia and performative explorations into how to protect and preserve animals and environments that are under threat.

Key to Safety Gear for Small Animals is the pretence of functionality. During the ICA exhibition visitors could access the 0.800.0Fauna0Flora telephone system, a free-phone service that gave advice on how to preserve plant and animal life. Users called to obtain information about current threats to flora and fauna, and to acquire guides and kits that might help stave off any impending doom. A user’s guide accompanied the phone service, providing a flowchart of the phone system, together with the transcript of each step in the service. Methodically, the service begins with step ’00’:

Welcome to the interactive voice mail system of the Flora and Fauna Information Service. If you want to learn about how to help imperilled animals, press 1; if you want to learn about our Bird Radio Programme or about Boilersuits for Primates, press 2; if you want to learn about how you can help preserve threatened plants, press 3; if you would like to skip to our sales items, press 4; to return to the main menu at any time, press 9.

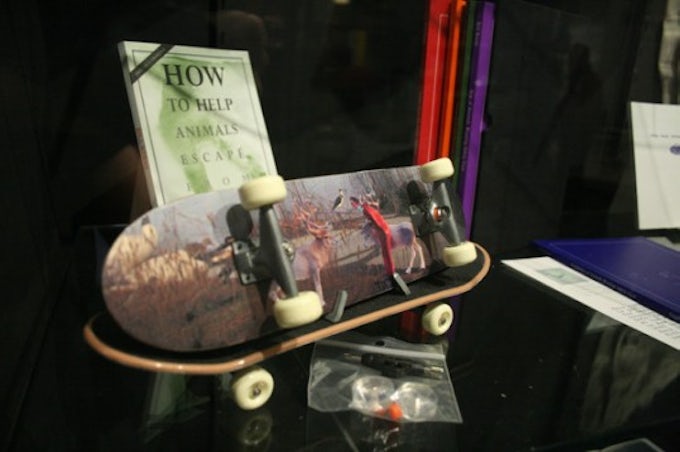

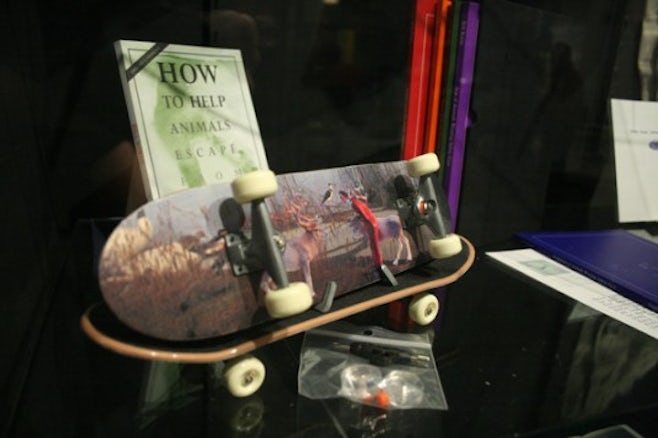

Each step in the phone system reveals a distinctive approach to ‘saving’ the environment. We can navigate, for instance, through option 1, which reveals the sordid details about the effects of chemicals, radioactive waste, wars, habitat loss and more on plants and animals. Options 2, 3 and 4 then point to strategies and remedies for imperilled flora and fauna. The phone service is suffused with equal measures salesmanship and humour, pointing not just to our environmental predicament, but also to the financial and quasi-rational means by which we address it. One may order kits and guides including Safety Gear for Small Animals; How to Help Animals Escape from Degraded Habitats; and 12 Steps to Underwriting Your Life Insurance, Will, or Annuities. The strange irony emerges that our model for learning how to save the environment is never far from the way we access our bank accounts.

The kits and book works that are a mainstay of the Safety Gear for Small Animals project feature largely in this service, and draw on the logic of field guides and self-help manuals alike. The0.800.0Fauna0Flora phone service and user’s guide further suggests that for certain information on flora and fauna we may wish to consult other guides provided by zoos, libraries or museums. While these guides may not provide ‘specifics on how to help imperilled animals relocate’, they are nonetheless ‘useful in identifying tracks, scat, mating calls and bird songs as well as providing information on diet, provenance and behaviour’. Often missing from the usual nature guides is any mention of how to address environmental distress. The Safety Gear for Small Animals ‘publication division’ fills this lacuna by providing a full array of environmental rescue texts.

Other publications within the Safety Gear for Small Animals series, which has been in production since 1994, include Urban Fauna Information Station, Footprints of Animals Wearing Safety Gear, Songs of Birds Wearing Safety Gear, a box-set of Safety Gear for Small Animal pamphlets issued to accompany the exhibition Safe: Design Takes on Risk at MoMA in New York in 2005, Bird Radio from the recent Berlin KW Institute for Contemporary Art installation in 2007 (also featured at the ICA) andHow to Help Animals Escape from Degraded Habitats. Each of these publications, which are typically minimal manuals and small pamphlets with exacting drawings, includes a high degree of detail on animal and plant behaviour, their performance under the influence of safety gear and means for their rescue. They remind us that despite our best efforts we often fail, if not tragically then at least comically, to comprehend the lives of animals.

The publications make a virtue of this shortcoming. How to Help Animals Escape from Degraded Habitats, an 80-page manual on offer in the 0.800.0Fauna0Flora phone service, creates a strange comedy of attempting to help animals by smuggling them in appliances to new homes. Accompanied by detailed diagrams, the guide wades through ‘the putative vastness of global destruction’ and offers practical strategies for relocating animals from ‘degraded habitats’ through the carrier of ‘appliance asylums’. Taking up the often-repeated mantra to ‘do something’, and adopting the acronym-marinated strategic language of big business, this how-to guide proposes a system termed ‘DRIVE’ (Discover, Retrieve, Innovate, Verify and Endow) for animal rescue. Through DRIVE, animals can be identified, secured, placed in small appliances, from cameras to shavers and refrigerators, and relocated to safer environs.

Bundled into these action-plans for nature rescue is the recognition that human intervention is often fraught with difficulty. Relocated animals may not always adapt to their new surroundings, and may even grow despondent and perish. The Safety Gear for Small Animals texts prepare us also for this environmental failure – both current and impending – by revealing how our defensive devices and procedures may offer rather feeble protection. Triage tents for furry mammals and guides to smuggling frogs in cameras make us query our strategies for dealing with risk and danger. By adapting the apparatus and language of rescue and safety to animal situations, Burns reveals with doses of humour and humility that saving the planet may require reassessing what it means to rescue, and to be rescued.

– Jennifer Gabrys