Amanda Carneiro: We would like to start by hearing from you about the relationship between your academic research and your curatorial practice. Considering the themes that interest you, how does this interaction take place?

Lilia Moritz Schwarcz: It is a good question but I don’t know exactly how to answer it, as I don’t see myself as a curator. It is not by accident that my title here at MASP is ‘Adjunt Curator of Histories’. I think through images and I have been including them in my work since my Master’s degree, as you can see in [the book] Retrato em branco e negro [1987]. Later, during my PhD, when I worked on the research that would become [the book] O espetáculo das raças [1993], my final thesis also included an exhibition. The experience was repeated in my free-docency thesis’ research on [the painter] Nicolas-Antoine Taunay [1755–1830] with O sol do Brasil [2008]. 01 My academic research has always been based on images, even though my premise is very different from traditional curators who, above all, think through art, curating artworks based on a point of view that unifies them. My premise is the opposite: I take themes in social and human sciences that interest me and from them I try to arrange the artworks and understand art.

In fact, I have worked on a number of exhibitions that were primarily historiographical, with the exception of Nicolas-Antoine Taunay in Brazil: a Reading of the Tropics [2008], which brought together Taunay’s artworks for the first time. The exhibition Mestizo Histories [2014], co-curated with Adriano Pedrosa [MASP’s Artistic Director] at Instituto Tomie Ohtake, was an important project where I learned about the different possible ways of being a curator. 02 Pedrosa challenged me to think about the relationship between artworks and at the same time I thought about them in relation to specific points of view. Mestizo Histories had already introduced issues related to post-colonialism and decolonialism, as it fused mediums, temporalities, geographies, and voices. These issues have been amongst my theoretical concerns for at least ten years, since I began to teach at Princeton, where these approaches are pivotal.

When Pedrosa invited me to join MASP, I became co-responsible for the project titled ‘Histories’, which is predominantly a concept developed by Pedrosa. I was extremely happy to witness Histories playing such a major role. The experience has challenged me to think with images: there is no point in having a fine theoretical argument if the images can’t speak for themselves. I think I used to have a very instrumental point of view, almost as if I saw images as illustrations in the sense that they were references to a context I already knew. Now I see that through my experience at MASP and the Taunay’s exhibition – as well as my work at Pinacoteca [do Estado de São Paulo] and Museu de Belas Artes – I have learned to delve much more into the reflective potential of the image. The image cannot escape the moment when it is made at the same time as it produces this same moment.

The work at MASP was a watershed, as I began to see images for what they are and, above all, to reflect on the colonial charge we have traditionally imposed on them in the way they are displayed in exhibitions. In other words, I began to search for ways to contextualize them at the same time as decontextualizing them. I admire the work of [French philosopher and art historian] Georges Didi-Huberman, who explores anachronisms, the displacement of senses, art mediums, heavily ingrained perceptions, which in the end are excessively colonial interpretations of art history. My practice here at MASP and also outside Brazil has helped me greatly, but I still see myself as a ‘curator’ with many quotation marks! Or at least as a hybrid curator.

André Mesquita: Didi-Huberman draws on Aby Warburg’s [1866–1929] Atlas Mnemosyne[1924–1929], which looks at the production of memory as stemming from the relations between images. Are these relationships enough to understand history or do we need a contextual support provided by documents?

LMS: I think images play a significant role. We – human scientists in general – are not used to approaching images with the same rigour we approach written documents with. For each written document we check its sources, we confirm dates, authors, recipients. Whenever possible, we find another parallel document that confirms the veracity of the first one. There are a number of methodological procedures for written documents that we do not follow when dealing with artworks. It is not uncommon for images to feature in the appendix. I think the place of the appendix in a book is very strategic: what does it tell the reader? That the fundamental information is written. The annex is a sort of extra gift. Readers are welcome to look at it if they wish. We often introduce images without providing context, such as dimension, year. We don’t question their authorship. This is a very pragmatic understanding of images, which are simply used to confirm what we already know.

I agree with you and with your reading of Warburg’s Atlas. Images are not producers per se: we must generate new meanings for them. Images produce images in a context and in relation to each other – this is Warburg’s theme in Atlas: to create a sort of mental setting in which these images produce a new reality that is not necessarily a reality that excessively depends on the context.

My readings of [Claude] Lévi-Strauss [1908–2009] on myths, on Mythologiques [1964–1971], were also fundamental, not only in relation to synchrony but also, and more importantly, in relation to the idea that myths say much more about each other than about their context, that is, Mythologiques makes me think of the forms of images, of how images acquire new meanings when put next to each other. This is what MASP’s Histories program has been doing: introducing tension and instability to artworks that enjoy a well-established and fully secured place in the canon.

AC: Do you believe in the provocation triggered by the Histories program as an open invitation to a broader audience to enter art spaces such as MASP?

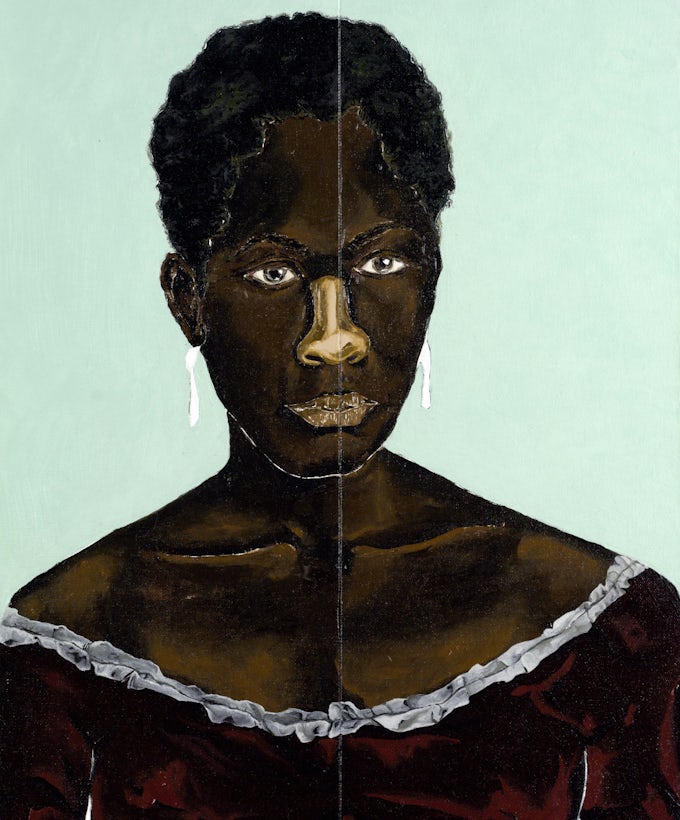

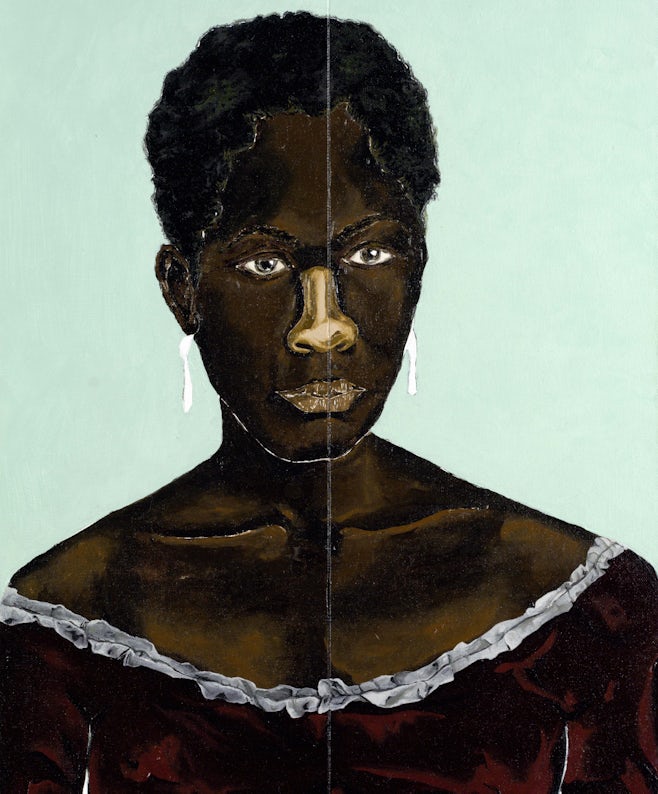

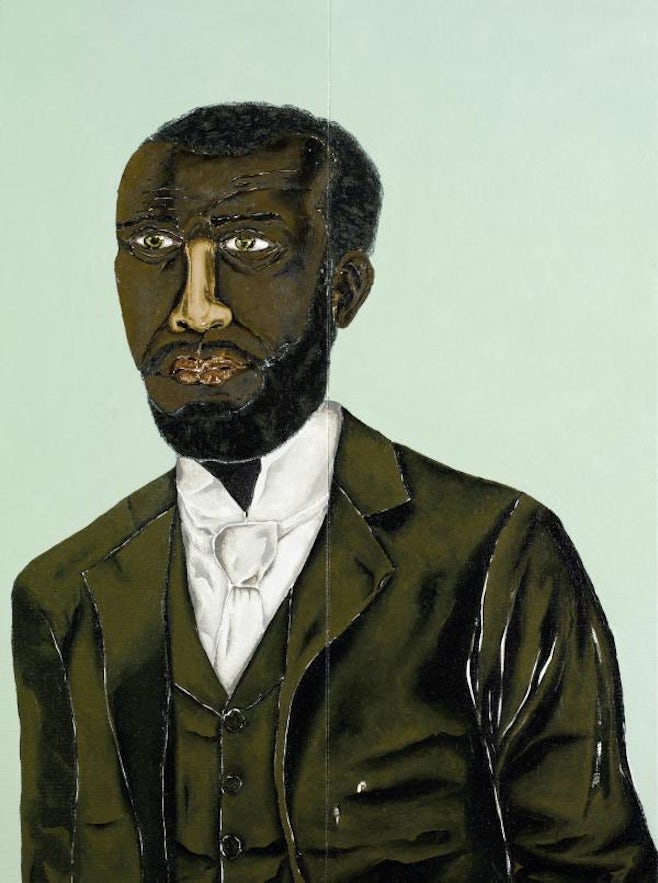

LMS: This is what I am referring to as the unspeakable, as explained by Haitian historian [Michel-Rolph] Trouillot [1949–2012], whose work I greatly admire: the worst rule is the rule we don’t speak about: the invisible rule. By denying these relations, we accept that the desirable audience, the public we ‘want’, the ‘Brazilian’ public is made of white people, between many quotes, generating mere selfies, including selfies [photographies] of Black people next to white characters. This shows the power of the unspeakable. The importance of these Histories is in the moments that force people not to recognize themselves or to recognize themselves. And I think this is difficult from all sides. The greatest moment for me – perhaps the moment that has touched me most profoundly – was the opening event of Afro-Atlantic Histories, which was packed! We said, ‘let’s make a picture gallery of portraits of Black people’. What is so unusual about that? The issue is that picture galleries are mostly white and male. It was very exciting to see a Black picture gallery filled with a Black audience. I think this was a revolution beyond the field of art: it was an institutional revolution that chose to question: ‘For whom is the museum on Avenida Paulista and how can the museum open up to the public that circulates outside?’ This was a much broader public than we normally see. But the struggle within other areas in terms of not bringing back the canon is also huge.

AC: Now that ‘Afro-Atlantic Histories’ cycle at MASP in 2018 has finished, having gained high visibility and expression in Brazil and also abroad, how do you assess the show?

LMS: My assessment is both positive and negative (I am always like that). The positive balance is that we have managed to attract a wider audience to the museum, and I hope that these visitors who felt invited continue to feel that way. I think Afro-Atlantic Histories inaugurated an agenda that we can no longer ignore. Therefore, in our upcoming show ‘Histories of Women, Feminist Histories’ it will be impossible not to include a Black, Atlantic, Afro-Atlantic perspective. I think that, on one hand, the exhibition played an important role, which was that of being amongst the best exhibitions in the world according to [The] New York Times. Here we have an interesting decolonial element, as in general, The New York Times typically awards North American and European exhibitions, without mentioning exhibitions from the Southern hemisphere, as if they were not worthy. So this is an important political aspect. It was also an exhibition that, as well as [Chief-Curator] Tomás Toledo, Adriano Pedrosa and myself, had two Black curators: Ayrson Heráclito and Hélio Menezes, who played a crucial role.

Both joined the team when the exhibition had already changed title: from ‘Histories of Slavery’ to ‘Afro-Atlantic Histories’. After the first seminar, which took place in 2016, we came to the conclusion that the original title would only suggest the negative aspects, leaving out the productive aspects, the strengths, and the actual symptoms. Even though the two curators joined the curatorial team when the exhibition’s sections and name had already been decided, they played a fundamental role, not only in terms of including artists, new Black artists, but also with the inclusion of new propositions and perspectives, which is always something fundamental. They opened up a huge path for us. In ‘Indigenous Histories’, the theme of the MASP programming cycle in 2021, the collective exhibition will be curated by Indigenous curators; therefore, we are – to a certain extent – radicalizing the scene. The idea is not to reiterate the idea of ‘having a voice’, which I think is problematic because the racial issue is not only a Black problem; there is no democracy with racism. I agree with [political activist from the USA] Angela Davis who talks about another belonging, but we must build a white antiracist movement that has a different place, a different space, but that certainly must work towards an antiracist society.

What negative side can an exhibition always have? To be closed in itself, closing down the dialogue. So I think we must make an effort now not to turn ‘Afro-Atlantic Histories’ into an event that has come to an end. We must preserve the tension. And how can we do that? By including all the other Histories in the stories we are set to narrate. In other words, we mustn’t think that each annual program ends with that year. In fact, it is almost a Babel Tower game: you touch a theme, you touch a symptom, and you continue to carry it along so it is not crystalized in that particular moment.

AM: To what extent was ‘Afro-Atlantic Histories’ key to articulating a decolonized style of curating, not centered on the main narratives of art history? Even though small, perhaps the first step was the exhibition ‘Histories of Sexuality’ [2017]. The section on activism brought together some artworks that made us reflect on a non-canonized art history, focusing on the actions of social movements, or produced by artists who had not been part of the official circuit, mainly in Latin America. 03

How do you see this broader issue in ‘Afro-Atlantic Histories’?

LMS: I think that in general terms, the program Histories has activated a significant movement of decentering, for instance, as I mentioned before, with the inclusion of Black and Indigenous curators who not only define the exhibitions but also support us in rethinking our curatorial practice. But I agree, I think ‘Histories of Sexuality’ played a key role in terms of decentering and proposing for the first time a model of curatorship from outside the museum. As a historian this is a very interesting process to follow.

But to what extent have we managed to actually decolonize our proposition? We have a massive challenge ahead of us in 2022, when we will reflect on our national histories and, with them, on our iconography, which is basically Eurocentric. Once again it will be fundamental to include new agents from the field of painting who bring with them new markers of social difference. They will help us broaden our perspectives.

AM: Talking about activism and also about new audiences in the field of art, and considering that ‘Afro-Atlantic Histories’ happened in an extremely complex political context, under a conservative wave, discussing racial issues amidst the violence perpetrated by governmental forces – [recently] substantiated with [the murder of human rights advocate and former councillor] Marielle [Franco] in 2018 and now with the death of Pedro Gonzaga, a 19-year-old man killed last week [14 February 2019] by a security guard working for a supermarket – it is important to reflect on how an exhibition can create a discourse in response to a policing and violent State.

LMS: On the day Jair Bolsonaro was elected president, I promised myself I would enact my opposition as a citizen. These new contexts demand a more public attitude from us, at least this is the way I see it. Not only through newspapers, as we know that not everybody reads them, but also on social media. We must defend [the idea] that the role of a critical museum has never been so paramount. I don’t think art should be completely servile to its moment, it doesn’t have to be an immediate reflection of the present but I think that the museum does belong to a context, to a country, a country that partakes in this huge conservative wave that we have seen in the world. I am talking about countries such as the USA, Poland, Hungary and Netherlands – and also Venezuela, on the other side. And this conservative wave has landed here amongst us. For me, the biggest problem is not right wing or conservative politicians (as long as they follow the rules of democracy). I fear what is happening in our country and other countries – which have already been called ‘democraduras’, that is, systems that proclaim to be democratic but are filled with information, measures and actions that are completely undemocratic and dictatorial. I think that democracy is an ongoing process. I don’t think it is about arguing that our 1988 Constitution should be fully fulfilled, as it already has had a number of amendments that demonstrate that a Constitution is only robust if it is resilient in the sense of allowing modifications that match what is happening in the world. However, the problem we have now is how to deal with the democratic project. I don’t think democracy is limited to the results of an election. Democracy is much more than that. Brazil is going through a continuous process of suppression of our civil rights. Rights are also like democracy: they haven’t been acquired forever. They are conquered via struggle and must be maintained via struggle.

Every one of us has our own instruments and MASP’s instrument is art. At present we cannot afford to work with exhibitions that are totally disconnected from our political moment.

AC: I would like to go back to the decolonial concept, as very little is said about it. Even though in Brazil there are a number of practices that could be read through a decolonial lens, they are still limited. How do you see the debates that articulate decolonial theories in academic research?

LMS: Once I gave a lecture in Princeton saying that in Brazil there was no decolonial discourse. I listed a number of reasons, which varied from reasons that are very strange to us to those reasons in which we already recognize ourselves. When I worked on the Taunay project, I did not have a decolonial argument. What does it mean to have a French painter of the Academy of Fine Arts coming to Brazil to depict the tropics? What does his detailed representation of slavery actually mean? Some people say we don’t have colonial problems because the Portuguese were wonderful colonizers. This is an argument we don’t agree with, but it is too strong to disallow a decolonial discourse. Others say that our colonization process was different so we can’t apply the same terms. These are mostly historians who focus on the idea that our independence was carried out by an emperor: a European, Portuguese emperor from the houses of Habsburg and Braganza, that is, a Bourbon. These are all well-known dynasties. Therefore, our decolonial process was an example of internal decolonialism, as it was headed by a monarch and for many years we had an emperor who was extremely popular. Some people also say that the decolonial discourse won’t ‘catch on’ in Brazil because we had – and these are all arguments I have heard before – a far-reaching and deeply rooted slavery regime, which makes it impossible to talk about a decolonial discourse. I think it took a long time for this discussion to be introduced in Brazil. And reasons for this are strong. For a long period of time, Brazilians refused to engage in this sort of political discussion.

AM: There is an ever-increasing concern with the representation of Black and female intellectuals, for instance, in academic debates and bibliographies. This space of discussion used to be much smaller as our academic background was strongly based on European authors, such as [Michel] Foucault [1926–1984], [Gilles] Deleuze [1925–1995], [Félix] Guattari [1930–1992], [Jacques] Le Goff [1924–2014] and other French historians. Today I feel things are changing: we have begun to think about the authors and arguments we are dialoguing with. The need to reflect on an alternative theory to investigate politics, art or activism also stems from a desire to assert the decolonization of our thought. Do you also see this today? Have these references changed in your work as a lecturer at Universidade de São Paulo [USP], for example?

LMS: Excellent question. I think this is a very slow transformation. If we look at the Social Sciences course, we still teach the ‘three little pigs’ as we used to say: [Max] Weber [1864–1920], [Karl] Marx [1818–1883] and [Émile] Durkheim [1858–1917]. The greatest references are always European or, at most, from the USA. And I still feel a very strong power of resistance to change.

At USP, I am part of a group called Group for the Study of Social Markers of Difference [Numas, in Portuguese], which investigates the intersection of markers such as race, gender, generation, region, class and religion. We look at meanings within these relations, within these intersections. This is almost self-mockery: I have been a member of Numas for a long time and for many years I taught a course called ‘History of Brazilian Social Thought from 1870 to 1930’, which did not include one single woman. The change is happening, but very slowly. For years I taught a course called ‘Reading Images’, which was basically a European course about Italian and French productions. We discussed Atlas then moved on to travelling painters and finally to the Academy of Fine Arts in Brazil. We read [Michael] Baxandall [1933–2008] and [Ernst H.] Gombrich [1909–2001]. I can’t deny the quality of these authors, but this year I am launching a course under the same title but with a different reading list. The list is not completely new as I still think these authors are fundamental, they are all authors we should read. But we should also include women and Black thinkers, and above all, Black painters. They used to be completely – I mean completely – invisible. So I think that slowly but surely the academic world has introduced other authors but I don’t think this is a quick process.

AC: I believe this discussion is linked to the criteria that qualify, validate or authorize certain researchers to become part of the academic field. Under the decolonial critique, these criteria have been through a strong process of revision. This has also been happening in museums. How can we rethink parameters of qualification and canonization?

LMS: This was already an important theme of debate in Mestizo Histories, which Pedrosa and I later brought to MASP. When we made Mestizo Histories, we relied on binary classifications, such ‘art and artifact’. Even our quotation rules [captions] were all Western rules, i.e., if a work’s authorship was collective it was difficult to quote it. At the exhibition opening, I saw some captions that said ‘Unknown Artist’ and I argued that they were actually known but that their communities didn’t necessarily work with the notion of individual authorship. This example shows how difficult it is for us to break with classifications. And these are cornerstone classifications that provide structure to our thought. I think that without breaking with these categories of classification – i.e. what qualifies a painter to be at MASP? What qualifies a thinker to be included in the syllabus of a course on the history of thought? – we won’t change these standards. And these standards are heavily loaded with political hierarchies. But I repeat: I don’t have to reject the authors that formed me. On the contrary, I still strongly admire many of them.

I should mention that Museu Afro Brasil has introduced these issues a long time ago, including material culture, the perversity expressed in objects of material culture. So they have been playing this role before MASP, which is something undeniable. I think we need to co-opt these classifications otherwise activism will remain outside academia. It will at most enter courses via the notorious division – which is also a division of value – between ‘compulsory subjects’ and ‘optional subjects’. I think we are slowing decolonizing the ‘optional subjects’ but the real challenge is to decolonize the ‘compulsory subjects’.

Footnotes

-

André Mesquita and Amanda Carneiro talk with anthropologist and curator Lilia Moritz Schwarcz

-

See Adriano Pedrosa and Lilia Moritz Schwarcz (org.), Histórias mestiças: catálogo. Rio de Janeiro: Cobogó, 2015.

-

For example, the actions carried out by ACT UP, Movimento de Arte Pornô, Mujeres Creando, Serigrafistas Queer, Yeguas del Apocalipsis, among others. See Adriano Pedrosa e Camila Bechelany (org.), Histórias da sexualidade: catálogo. São Paulo: MASP, 2017.