Amidst the bustle of a burgeoning Brazilian art market, the International Director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA), Jay Levenson, travelled to Brazil for the third time in 2012, crisscrossing the country to visit contemporary art institutions and fairs. Speaking to the Folha de S. Paulorecently, he recalled a shared past, when MoMA first purchased a work of art by a Brazilian artist, and also framed a common future, resulting in a major exhibition of Lygia Clark’s work in 2014 and a publication of texts by art critic Mario Pedrosa.01MoMA’s plans can be understood within the context of a self-proclaimed mission to promote Latin American art, but also as a symptom of an increased interest in Brazil across the US and Europe, at a time when the country – and its art market – fosters a stable economy in the midst of a global economic crisis.02

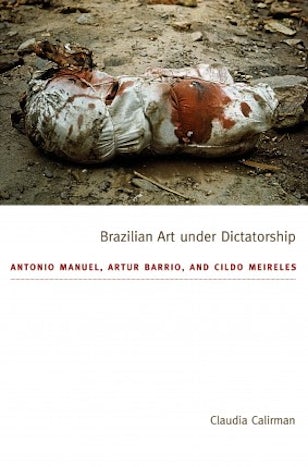

Claudia Calirman’s recently published book Brazilian Art under Dictatorship: Antonio Manuel, Artur Barrio and Cildo Meireles (Duke University Press: Durham and London, 2012) clearly speaks to this context. Focusing on the actions carried out by these three artists under the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964 until 1985, the book pays a particular attention to the political and artistic events occurring as a consequence of the enactment of the Ato Institucional no. 5 (Institutional Act no. 5, also known as AI-5) in 1968 – an unconstitutional decree that introduced the state of exception and ‘officialised torture’03in Brazil – and asks:

How to reconcile the political agenda with artistic innovation in a country under censorship? Could artists be at once politically active on a local level and engaged in international artistic developments? Could they find an alternative to conventional models of social activism, which almost always sacrificed aesthetic quality for ideological agenda?04

These questions to a great extent predetermine the outcome of the author’s research, which offers a reading of Antonio Manuel, Artur Barrio and Cildo Meireles’s work as a response to the censorship and the violence of the military regime, particularly during the period 1968–75, which culminated in the use of systematic torture and the arrests of students, politicians, intellectuals and artists. A chapter is dedicated to each artist, drawing a central thread from the characteristics that unite their practices: firstly, the refusal to confront the dictatorship using a protest art of nationalist intent – a recurring and apparently efficient model much used since the end of the 1950s, as it served to clearly identify the ideological poles of the left and the right, in terms of both ideas and action.05 Secondly, the particular and innovative ways in which they each responded to both censorship inside the country and international artistic trends. Instead of working with traditional media such as painting and sculpture, they all chose media of an ephemeral nature: Antonio Manuel worked with performance and body art, Artur Barrio advocated the use of decaying, degradable and inexpensive materials as the basis for site-specific works, and Cildo Meireles developed a conceptual art practice.06 Such is their survival strategy: in their attempt to evade censorship, these artists developed modes of expressing themselves indirectly.

The merit of Calirman’s book lies in the manner it documents a well-known story, albeit one that is still revisited with caution, especially within Brazil. The volume of information included contrasts, however, with the author’s often schematic explanations and categorisations, where the value of Brazilian artistic production is endorsed by better known and earlier artistic practices from North American and Europe.07 Calirman’s argument for the incontestable critical power of Cildo Meireles’s Inserções em circuitos ideológicos: Projeto Coca-Cola(Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project, 1970), for instance, is weakened by a final articulation of the artist’s work in relation to that of Andy Warhol through dispensable conceptual and formal links, and to that of Michel Foucault, through interpretative ones. Her analysis of Antonio Manuel’s work uses the artist’s intervention at the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro,The Body Is The Work (1970), to categorise his practice during the period as body art, connecting it to Vito Acconci and Robert Morris, though noting that it’s marked by the celebratory worship characteristic of the Carioca culture, which is ultimately another category that could be deconstructed.08 The same happens to Artur Barrio, whose work ‘does not fit neatly into any one movement of the period during which he made his art’, but is then placed in relation to Joseph Beuys’s sculptural practice and – with a degree of opposition – to Robert Smithson’s earth-based works.09

In order to delineate the artistic and political context of the late 1960s in Brazil, Brazilian Art under Dictatorship opens with a discussion of the artists’ statement ‘Non à la Biennale de São Paulo’ (‘No to the 10 Bienal de São Paulo’), a document produced in Paris in June 1969, which expressed foreign artists’ outrage against the brutality of the regime, gave an account of the violence perpetrated against Brazilian artists and intellectuals and called upon artists of all nationalities to boycott the 10th Bienal de São Paulo.10 The large support that it gained (the document carried 321 signatures) and the significance of those involved in that protest, amongst them art critic Pierre Restany, speaks of the Bienal de São Paulo as a paradigmatic institution of Brazilian cultural history.11The importance of the Bienal – and its symbolic representation of certain social classes aligned with the military regime – is further exemplified by the refusal to participate of the following Brazilian artists: Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark, Rubens Gerchman, Willys de Castro, Nelson Leirner, Mary Vieira, Antonio Dias and Carlos Vergara, among others.

The merit of Calirman’s book lies in the manner it documents a well-known story, albeit one that is still revisited with caution, especially within Brazil.

The author also offers a detailed account of the obstacles found by the then-director of the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), György Kepes, when he was invited to organise an exhibition around art and technology for that edition of the Bienal de São Paulo. However, Calirman overlooks the reverberations of the boycott in the US itself, missing an opportunity to acknowledge the importance of artists’ actions in the US, which continued even after the end of the exhibition in São Paulo. Led by Gordon Matta-Clark,12 artists of the Museo Latinoamericano continued the demonstration,13 publishing and circulating the book Contrabienal (1969), which functioned as a parallel exhibition to protest against the Brazilian dictatorship and its use of torture.14 In choosing to ignore the expanded protest of these Latin American artists in the US, Calirman loses sight of a complex web of contradictions lived by Latin American intellectuals and artists in exile.15

The detailed descriptions of specific events engender many other questions, which await deeper investigation and call for a more profound analysis. For example, a comprehensive report on the artistic community’s unabated outcry and international debate on whether to boycott the Bienal or not is brought to an end by a description of the opening of the exhibition itself and its numerous visitors, even if they were alienated from the events taking place backstage. Appreciative of the ironies and contradictions of these events, Calirman nonetheless discards their development in favour of a panoramic view of the period, inadvertently reducing their importance.

Aimed at being diagrammatic, somewhat in the manner of Alfred Barr Jr., the book does not dispense enough attention to the details that are important to historical writing, and this inevitably results in factual errors. For instance, in her discussion of the exhibition ‘Do Corpo à Terra’ (‘From Body to Earth’, 17–21 April 1970), held at Belo Horizonte’s Municipal Park, in the state of Minas Gerais, the author questionably points out that the exhibition was ironically sponsored by the military government even though it celebrated the Brazilian struggle for independence from Portuguese domination.16Indeed the date of the celebration was chosen to mark the hanging of Tiradentes, leader of an uprising on 21 April 1792 in Minas Gerais; his body subsequently dismembered. This event was commemorated in the exhibition by Meireles’s Tiradentes: Totem-Monumento ao preso político(Tiradentes: Totem-Monument to the Political Prisoner, 1970), an installation in which chickens were burned alive, thereby associating the violence employed by the Portuguese colonisers to that of the military government. The piece eventually precipitated the seizure of the exhibition,17 which was closed down by the police following a complaint.18 However, as the curator Frederico Morais notes, the exhibition was sponsored by Hidrominas, a tourism agency of the State of Minas Gerais;19 which did not make it representative of the military government. On the contrary, it demonstrates that this was a time of dissent across the left and the right, and that the Brazilian dictatorial government – composed by the military but also connected to part of the country’s industrial bourgeoisie – had housed its contradictions.

By reducing the reading of these artists’ work to a response to the historical events of the past, an opportunity is lost to enquire about the significance of studying them today.

In addition to the importance of the political events that it triggered, this exhibition also had a significant artistic importance: Morais indicates that this was the first exhibition in Brazil where ‘artists where invited not to exhibit their concluded artwork, but to create work directly on site. As such, they had their travel and accommodation expenses covered, and also received a stipend, along with artists from the state of Minas Gerais.’20 This fact per se merits special attention, as it shows the degree of innovation that existed in the relationships between artists and curators, including the reversal of their roles.

The didactic tone of the book ultimately affects the discussion of the artists themselves, otherwise so closely studied. Calirman disappointingly concludes by tying their separate trajectories to current hegemonic categories of art history and criticism. Antonio Manuel, for instance, is associated to body art and media art. In search of a new aesthetics representative of a peripheral country – one marked by precariousness – Calirman also refers to Artur Barrio’s ‘artworks in public spaces, merging political content with non-permanent artistic practices’ and is interested by the way in which Meireles’s conceptual practice was exhibited in a very genuine way, both politically and formally.21

By focusing exclusively on Meireles’s artistic activities at that time, Calirman effectively demonstrates the political and critical nature of his work. However this is gained at the risk of ultimately rendering the impression that his greatest contribution was the ability to anticipate international trends and their operation in the local context. Again, diagrammatic solutions simplify a picture that is rather more complex. Still the reason for studying these artists at present is not made clear: is it to find that – at that moment – they already fit hegemonic models?

The recollection of the past is aimed at opening the doors to the present. By reducing the reading of these artists’ work to a response to the historical events of the past, an opportunity is lost to enquire about the significance of studying them today. How can a political agenda be articulated within today’s international art scene and globalised world? Is it possible to define global networks as public and democratic spaces per se, devoid of any kind of censorship? How to articulate artistic density and critical power that is able to respond to new models of social activism? The questions keep arising.

Footnotes

-

The first South American work acquired by MoMA was Candido Portinari’s painting Morro (1933), in 1939. See Silas Marti, ‘MoMA intensifica relação com Brasil em mostra e livro’, in Folha de S.Paulo, 14 September 2012.

-

See Ana Leticia Fialho, ‘Brazil in the MoMA Collection: An analysis of the insertion of Brazilian art in an international art institution’, in springerin, issue 3/05, 2005, available at http://www.springerin.at/dyn/heft_text.php?textid=1673&lang=en

-

The expression ‘official torture’, used in regards to AI-5, was coined by the critic and curator Frederico Morais, whose archive and testimony were the basis for the book.

-

Claudia Calirman, Brazilian Art under Dictatorship: Antonio Manuel, Artur Barrio, and Cildo Meireles, Duke University Press: Durham and London, 2012, p.2.

-

An example of this kind of practice is the CPC – Centro Popular de Cultura (Popular Culture Centre), a group organised by urban, middle-class students in order to transform popular culture – of rural origin – into a political tool, which intended to build a new culture: ‘popular, national and democratic’. For more information, see http://www.itaucultural.org.br/aplicexternas/enciclopedia_ic/index.cfm?fuseaction=marcos_texto_ing&cd_item=10&cd_idioma=28556&cd_verbete=5001

-

See C. Calirman, Brazilian Art under Dictatorship, op.cit., p.42, 80 and 8 for a discussion of the media chosen by Antonio Manuel, Artur Barrio and Clido Meireles respectively.

-

The book review by Michael Asbury published in Art in America in June 2012 also points out the author’s difficulty in leaving the hegemonic categories aside, and indicates other gaps in the text. See M. Ashbury, ‘When art spoke to power’, Art in America, June 2012, available at http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/books/when-art-spoke-to-power/

-

C. Calirman, Brazilian Art under Dictatorship, op.cit., p.44

-

Ibid., p.109

-

The visceral letter by Gordon Matta-Clark, published in Artforum on 19 May 1971, was reproduced in the 27th São Paulo Bienal Guide and is available online at http://issuu.com/bienal/docs/27a_bienal_de_sao_paulo_guia_2006

-

The Museo Latinoamericano was a group of New York-based Latin American artists, including the New York Graphic Workshop group, Luis Camnitzer, Liliana Porter and José Guillermo Castillo. For more information, see Isobel Whitelegg, ‘The Bienal de São Paulo: Unseen/Undone (1969-1981)’, in Afterall, issue 22, Autumm/Winter 2009, pp.106–113, available at http://www.afterall.org/journal/issue.22/the.bienal.de.so.paulo.unseenundone.19691981

-

Supporters included, amongst others, every artist and intellectual that had been selected by Restany for the French representation at 10th Bienal (1969), all of whom later declined to participate. In the end the French representation was limited to an exhibition of tapestries, organised exclusively by the French Ministry of Cultural Affairs. There were also signatures from the US, Belgium, Mexico, Holland, Sweden, Argentina and Italy. See Renata Zago, ‘A Bienal de São Paulo ou Pré Bienal de 1970’, lecture given at the conference Encontro de História da Arte – UNICAMP, 2010. Available at http://www.unicamp.br/chaa/eha/atas/2010/renata_cristina_oliveira_maia.pdf

-

See Caroline Saut Schroeder, ‘X Bienal de São Paulo: sob os efeitos da contestação’, Master’s Thesis, University of São Paulo, 2011, available at http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/27/27160/tde-26112011-133939/pt-br.php, and also I. Whitelegg, ‘The Bienal de São Paulo’, op.cit, p.108.

-

For instance, the American government played an active role in the coup d’etatagainst the democratic president João Goulart (1961–64). For more information, see Caio Navarro de Toledo. ‘1964: O golpe contra as reformas e a democracia’, Revista Brasileira de História, vol.24, no.47, São Paulo, 2004, available at http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0102-01882004000100002&script=sci_arttext. Additionally, the kidnapping of the US ambassador in Brazil, Charles Elbrick, in 1969 had symbolic significance – drawing global public attention to the ambiguous nature of the relationship between American democracy and military dictatorship in Brazil.

-

C. Calirman, Brazilian Art under Dictatorship, op.cit., p.122

-

Calirman also leaves out the fact that the image of Tiradentes, as a figurehead of the republican cause, has been used historically by those rebelling against Portuguese domination. Carefully constructed by republican authors since the 19th century, the image of Tiradentes was particularly exploited by another authoritarian government, that of Getúlio Vargas (1937–45), with the aim of fabricating a national identity by reinforcing the role of Vargas as a martyr, sacrificing himself for the nation. For more information, see Thais Nivia de Lima e Fonseca, ‘A Inconfidência Mineira e Tiradentes vistos pela imprensa: a vitalização dos mitos (1930-1960)’, in Revista Brasileira de História, vol.22, no.44, São Paulo, 2002, available at http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0102-01882002000200009&script=sci_arttext.

-

See Gonzalo Aguiar’s interview with Frederico Morais, ‘Frederico Morais, o crítico-criador (Frederico Morais, the critic-author)’, Cron ó pios, 25 May 2008, available at http://www.cronopios.com.br/site/colunistas.asp?id=3279

-

See Frederico Morais, ‘Do Corpo à Terra – Um Marco Radical na Arte Brasileira’, 2001, available athttp://www.itaucultural.org.br/corpoaterra/texto_curador.pdf

-

Ibid .

-

Ibid .

-

C. Calirman, Brazilian Art under Dictatorship, op.cit., p.8.