i had a nice dick, average length and all

i wanted ron to look at it, want it

dada is our intensity; it erects inconsequential bayonets and the sumatral head of german babies. 01

To launch the Black Dada Reader and on the occasion of his exhibition ‘shot him in the face’, Adam Pendleton performed his ‘Black Dada Manifesto’ (2008) with rhythmic modulation in the courtyard of Berlin’s KW Institute for Contemporary Art. The manifesto appears in the reader alongside a compilation of foundational texts, essays and the positions of other artists assembled by Pendleton in the intervening years to map out his concept of Black Dada.

Having already visited the exhibition, it was hard for me to cohere the blood and bone, not to say, simply, the sex of the courtyard with the sans serifs of the third floor of the art institute. For all the verve of Pendleton’s voice that day, his installation relays rather a stiff discomfort. One might call it ungenerous, or as the art historian Tom McDonough did, writing about Pendleton’s work in Artforum back in 2011, ‘reticent in the extreme’. The orderliness of his lettering, McDonough claims, imbues the works with a paradoxical coolness that belies their highly lyrical content. 02

This rings true of Pendleton’s output as I have encountered it through the Reader, the performance in the courtyard, and the exhibition at KW: suspended between a call to arms, a declaration of love, and a detached, wilful abstraction. It’s Black Dada. But what does that mean?

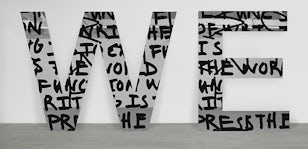

The (il)logic of Pendleton’s visual as well as textual production, between which there is little reason to distinguish, can be understood as parataxis: in grammar, the placing of words or clauses one after the other without words to indicate coordination or subordination. With each unit independent, meaning is at once produced and troubled through succession. ‘Albany’ (1946), a poem by Ron Silliman, is composed out of one-hundred such paratactic sentences, and ‘shot him in the face’ takes as its starting point the opening line: ‘If the function of writing is to “express the world”’. Set in Pendleton’s custom bold Arial font, fragments of the sentence are superimposed across the immense wall that bisects the room floor to ceiling, overlaying disparate images: the first Documenta, people dancing at the independence celebrations of the Democratic Republic of Congo, then at a Dada event in Zürich, then a page of writing by Malcolm X. Obscured and scattered, the text is recognisable but ultimately illegible, rendering this side of the wall a stubborn enigma.

Pendleton stands at once with and against the history of modern art, positioning Black Dada ambivalently as a potential ally, as well as a disruption to its supposed objectivity.

As such, the proximity he stages is always fraught and never resolved. It is not reparative, and not interested in narrative, but a formal offering. This, a cornerstone of Pendleton’s project, has to do with forging, not exactly lines of kinship, but frameworks for co-presence, jarring and irrespective of time and space.

On the backside of the wall, one of his Black Dada paintings is offset at the far end of the room by a 1966 red monochrome by South African conceptual artist Ian Wilson. Pendleton’s series, begun in 2008, crops and enlarges photocopied reproductions of Sol LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cube (1974) onto a black screen-print, also featuring individual letters in bold Arial from the words ‘Black Dada’. Pendleton first found this term in a poem by Amiri Baraka, 03 whose violent, breathless intensity seems greatly at odds with the calculated calm of both Wilson and LeWitt. However, while LeWitt’s cubes figure the most essential units of a type of language, Pendleton invites us to think about what one might do with such a language; how one might also render LeWitt’s own project differently through it. Already in 1978, Rosalind Krauss suggested LeWitt’s obsessive prolificacy be read as a kind of ‘babble’. 4 As Pendleton writes in his manifesto: ‘History is in fact an incomplete cube shirking linearity.’ Here, he stands at once with and against the history of modern art, positioning Black Dada ambivalently as a potential ally, as well as a disruption to its supposed objectivity.

The Reader functions in the same way, staging a cacophony of voices, the dissonances between which are as galvanising as they are perplexing: the scholar W.E.B. Du Bois, film-maker Jean-Luc Goddard, poets Gertrude Stein and June Jordan, musician and performer Sun Ra and artists Thomas Hirschhorn, Joan Jonas, Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Adrian Piper, to name a few. As in Pendleton’s installation, the texts appear as photocopies, adding to the dissolution of single authorship, orchestrated also by the format of the reader itself. This, and the points at which these texts collide, figure a kind of abstraction that corresponds to that of Pendleton’s visual production. ‘Abstraction is also flight’, he quotes from Adrian Piper, ‘it is freedom from the immediate spatiotemporal constraints of the moment … [and the] boundaries of concrete subjectivity.’ Pendleton’s illegibility, then – the impersonal orderliness of his lettering – is a guard against essentialism and biography; a way of becoming multiple without expending the self.

Leaning against the wall are the letters ‘W E’ cut out of mirror, eclipsed by printed text and black and white image. The work recalls Glenn Ligon’s Give us a Poem (Palindrome #2) (2007) a neon sign reading ‘ME / WE’, each word lighting up interchangeably. Pendleton responds to Ligon’s reflection on the dialectic between individual and collective with the decisive exclusion of ME. Here, the single subject is instead, as Gonzalez-Torres writes to Andrea Rosen in a text included in the Reader, like ‘an empty passport for life’: ‘a simple white object against a white wall, waiting’. With Black Dada Pendleton constructs a nonsensical yet insistent We, which, in this very reticence, allows individual subjects unbound by the binaries of identity. ‘We come from otherwhere,’ the manifesto reads, ‘in part we grew by looking back at you.’