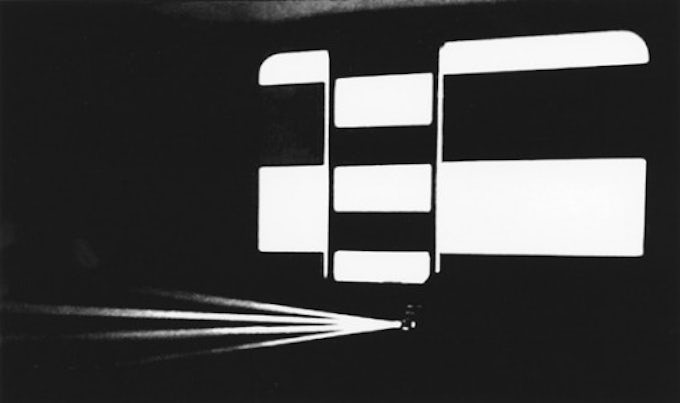

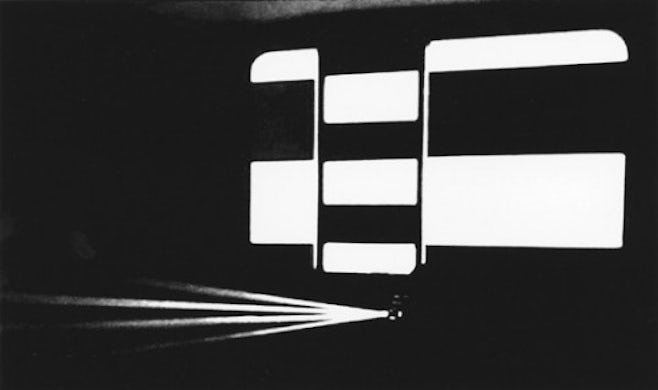

In Lis Rhodes’s expanded cinema piece Light Music (1973) two beams of light, thrown by two projectors sitting on the floor facing each other, are made visible by fog created in the room. The patterns they project on the wall – stripes running up and across, white squares, quick flickers – are, to an extent, legible in the throw: the striated splintering of the beam corresponds, for example, to stripes projected on the screen. This is a process that takes time – not for the process to occur, but for the spectator to become aware of it, and to be affected by it – time to connect the shapes to the forms manifested or contained by the beam, and time to settle down and take it in.

Light Music was shown in one of this year’s programmes at the Oberhausen Short Film Festival (2008), a festival in the German town, near Düsseldorf, which has historically shown politically engaged short films (each must be under 45 minutes long) and has recently been turning its focus to artists’ moving image works as well. Held in early May, the festival ran two curated programmes alongside its juried competition and international distributors’ segment: both these programmes addressed political filmmaking, and particularly political filmmaking from the late 1960s and 70s.

The London-based curator Ian White selected the programme ‘Whose History?’, a title taken from a Rhodes essay of the same name, while the New York-based filmmakers Sherry Millner and Ernest Larsen selected ‘Border-Crossings and Trouble Makers’. Though the crossover between the two programmes was evident – Joyce Wieland’s Solidarity (1973) was screened in both, for example – the approach to politics diverged. Millner and Larsen screened films about struggles around the world, casting a wider net of geographical diversity and displaying a certain topical approach to politics: a film is political if what it represents is political. White’s approach had a more complex articulation, looking at work in its various registers – content as well as form, for example, and feel, affect and genre. In one screening, for example,Solidarity was paired with Malcolm Le Grice’s expanded cinema performance Castle One (1966), an association that was based as much on subject matter as formal correspondence: the word ‘solidarity’ that remains at the centre of the screen during the Wieland film, which documents a worker’s strike at the Dare biscuit factory in Ontario, was echoed by the (actual) light bulb in Castle One, which dangled in front of the screen in the same spot. The German filmmaker Alexander Kluge’s work was a key touchstone, appearing in a number of different screenings; Kluge’s films could perhaps be seen as White’s parallel to the way Roger Buergel and Ruth Noack used John McCracken paintings and sculptures in their documenta 12 (2007), where they reappeared almost as punctuation marks throughout the exhibition.

The difference between the two Oberhausen programmes, one topical, one performative, came to light during a panel discussion, moderated by Millner, that brought together the Berlin-based filmmaker Hito Steyerl, the Serbian filmmaker Zelimir Zilnik, the Lebanese curator Rasha Salti and the US artist Martha Rosler. In the at times cantankerous debate, it became apparent that affinities ran along national lines, with Millner and Rosler much more supportive of film’s potential to represent and publicise conflict, and the European contingent more concerned with how film and the moving image functions in the real world. Steyerl in particular discussed the dissemination of film, for example via Facebook, YouTube or Piratebay, siting politics as much in the cultural product as in the economics and politics that surround its exhibition or acquisition. She used the example of rioting in Malaysia after a crackdown on pirated DVDs in the West, the sale of which constitutes a substantial industry in the Southeast Asian country – what is easy access to the Bourne Ultimatum (2007) for some is food and water to others. There was also inevitably much discussion over the value of showing political films in a film festival – are you not preaching to the converted? Is it not too specialised an audience? Steyerl countered this by what she calls ‘the Marie Antoinette dilemma’: with the shutting down of the possibilities of screening films in publics spaces or in publicly shared platforms such as television, the only option artists have left is ‘cake’ – that is, the luxury of museum programmes, gallery installations and well-funded film festivals.

This divide between films ‘about’ politics and analyses of ways that films make or take part in political systems was eruditely summed up by the British filmmaker Judith Wilkinson, who was in the audience. Wilkinson referred to Roland Barthes’s distinction in Mythologies (1957) between language that remains political and what he calls the depoliticised, bourgeois language of myth:

If I am a woodcutter and I am led to name the tree which I am felling, whatever the form of my sentence, I ‘speak the tree’, I do not speak about it. This means that my language is operational, transitively linked to its object; between the tree and myself, there is nothing but my labour, that is to say, an action. This is political language…01

This idea of transitive language as an analogue for labour and immediacy – suggested also in the projector throw of Light Music, which ‘speaks’ the patterns it later projects on the wall – is opposite to the approach taken by Millner and Larsen’s programme, which treated politics as subject, something that is spoken about:

Compared to the real language of the woodcutter, the language I create is a second-order language, a metalanguage in which I shall not henceforth not ‘act the things’ but ‘act their names’, and which is to the primary language what the gesture is to the act02

Such a tall order – programming that ‘speaks the tree’ – appeared to be one of the main goals of White’s ‘Whose History’, which dealt consciously with the effects of films on the body, and especially on the individual audience member as he or she passed through the programme in time. Time, indeed, is an explicit subject of many of Kluge’s films, and as White’s programme developed it was clear he was banking on a dedicated film audience being able to make connections among screenings spread out across a number of days. This idea of ‘time’ as something that is necessary to one’s understanding of film seems self-evident, but it is often absent from much core film scholarship investigating the phenomenology of film (such as Kaja Silverman’s The Threshold of the Visible, 1995, or Vivian Sobchack’s The Address of the Eye, 1991). It is interesting to compare White’s emphasis on connections that rely on time in order to constitute themselves in the mind of the viewer with the idea of the ‘migration of form’, a presiding notion of documenta 12 that aimed to evoke in the viewer the fact of the migration of form and content across geographical boundaries and time, precisely by his or her own ambulatory migration through the gallery space. By doing so, both White’s programme and documenta 12 leave themselves radically open to the individual experience.

Returning to Oberhausen, it seemed a shame that both programmes focused on the same subject, especially in a month – the fortieth anniversary of May 1968 – which was dominated by retrospective political thinking. Artforum also devoted their issue to May ’68; in which a quote from Liam Gillick, paraphrasing Philippe Parreno on thesoixante-huitard strikers, caught my eye: ‘it would have been better if the progressive forces of the past had expended more effort occupying time rather than space’.03In a similar way, while Millner and Larsen were concerned to represent, as best as possible, the struggles of the globe, White’s programme seemed to respond better to the notion of political filmmaking by concentrating on – creating? – change through time.

————

Response by Ernest Larsen:

In her essay-review of the 54th International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, Melissa Gronlund sketches a position on the character of political film, tendentiously setting Ian White’s “Whose History?” programs against the programs that Sherry Millner and I curated, titled “Border-Crossers and Trouble-Makers.” If possible, I’d like here to rescue both of our distinctive series’ from the uncertain grip of Gronlund’s argument. On the one hand, she claims, the films we chose “display a certain topical approach to politics: a film is political if what it represents is political.” On the other hand, “White’s approach had a more complex articulation, looking at work in its various registers – content as well as form, for example, and feel, affect and genre.” “Border-Crossers” is portrayed as somewhat naively engaged in representing struggles around the globe while “Whose History?,” in Gronlund’s estimate, “seemed to respond better to the notion of political filmmaking by concentrating on – creating? – change through time.”04

Let’s set aside the obvious point that nothing about the first approach precludes the second – there’s never been a film made that doesn’t represent the potential for change (however broadly defined) through time. Furthermore, like White’s programs, ours aimed to take deliberate advantage of the short film format to create more complex webs of connections within each program and across programs. That is one of the most compelling aspects of the role of the curator. As the title “Whose History?” strongly intimates, Ian White’s adventurous and extremely knowledgeable programs ambitiously reconsidered the canon of what he calls “artists’ films,” decisively unsettling the conventional view that groups quite obviously non-political experimental films with directly political – or consciously politicized – work.

Strangely, there is no way to tell from Gronlund’s account if she actually experienced – that is, saw with her own eyes – any of our programs, or even whether she viewed a single one of the films, since she never mentions any of the dozens of works we included except for Solidarity (Joyce Wieland, 1973), the only film we programmed in common with White. She incorrectly claims that, like “Whose History?,” our selections concentrated on ’60s and ’70s film when in fact we showed many more recent (post-2003) films. Our specific interest (as stated in our catalogue essay) was to understand and seize hold of the transformative possibilities of political, experimental film in relation to what is commonly regarded as the historical rupture of 9/11. Taking what we call “the unreconciled intransigence of Buñuel’s Las Hurdes(1932) as an impossible standard,” we sought out “post-9/11 essays in human geography,” and it soon became clear that an approach that set out toward the new was not limited to films produced in the past few years but to films that, no matter when they were produced, “still forced or facilitated distinctive reckonings with the historical moment in which we live,” films that “when screened have the feeling of unkept promises, of a barely tapped potential.”05

For example, our first program, titled “Dirty Movies,” situated certain artists’ films within a scattering of even less easily classifiable films, none of which could be said simply to represent “struggles,” global or otherwise. In this sequence Pawel Wojtasik’s formally impeccable Dark Sun Squeeze (2003); Ausfegen (Sweeping Up), an all-but-unknown documentation of a site-specific Joseph Beuys performance from 1972; and Garbage (1968), a film that simultaneously documents and critiques a street action by the political/artists collective Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers, were set alongside films like Aubervilliers (1945), the only film directed by Elie Lotar (the cinematographer for Las Hurdes) – a kind of lost or at least overlooked masterpiece that links the liberating cruelty of Buñuelian surrealism with the lyricism of the French Popular Front. Overall, “Dirty Movies” was organized to explore the question of what it is in the social order that counts as dirt, an approach that is at once metaphorical and material. All of our other programs employed this same dialogical tactic, such as “Excessive Behavior,” in which the films we chose examined the relations between the performative and the political.

Of course, none of this matches Gronlund’s ungrounded notion that we “treated politics as subject.” It was precisely the point to avoid the tiresome trap of disconnecting the representation of the political from such arenas that are too readily counted (and even more readily valorized) as “formal.” Another example, even closer to home: Sherry Millner and I produced a two-screen remake of Guy Debord’s 1961 Critique of Separation, titled Partial Critique of Separation (2008), which self-reflexively resituated that film, playfully applying the indispensable Situationist principle of political/aesthetic intervention, détournement. In juxtaposing the here and now (New York, 2008) with the there and then (Paris, 1961),Partial Critique of Separation proposes that the material conditions that separate each from all and self from self, and that at every moment militate us against the imperative to resist, persist. But it would take some heavy-duty arm wrestling to turn this film into a representation of a struggle.

Gronlund’s essay is sprinkled with many other relatively minor, if annoying, mistakes. It should be pointed out, for example, that the Lebanese writer Rasha Salti, whom Gronlund places on our panel with her review, was unable to attend the festival. And it will certainly shock the cultural critic Judith Williamson, whom Gronlund doubly misidentifies as the British filmmaker Judith Wilkinson, to find her brilliantly relevant remarks about mythic speech via Barthes quoted in support of abstraction. She was clearly in strong vocal support of “Border-Crossers” in her critique of the ways that strict formalism leaches out any concrete sense of politics, while seeking to maintain the theoretical sheen of the political – a brand-new paint job on the same old clunker, as it were. But forget all that. Forget, too, her stumbles over the ways in which film inevitably structures our experience of time, a fact even she admits is self-evident. Much more troublesome are her remarks on how to decide what is political in experimental film. It is the province of experimental film to raise questions about film itself – experimental films are by definition meditations on the filmic, and on the effects of the filmic on consciousness. It is simply a misuse of terminology to claim that formally challenging films must therefore also be – in something other than the broadest, most uselessly abstract, and ultimately mysterious manner – political. Some day someone will be either mischievous or overly serious enough to put together a history of “political” film in which nothing of any political substance whatsoever is broached.

I have to admit that I’m as impressionable as the next guy, so when Gronlund said that “Whose History?”‘s sense of the political was more complex than whatever it was that we were after in “Border-Crossers and Trouble-Makers,” I started thinking, “Well, that could be – maybe we didn’t step up there in the ambition sweepstakes like we thought we did.” But then Gronlund furnished an example of the complexity she had found: The way the real light bulb placed in front of the screen during Malcolm Le Grice’s film, Castle One (1966), lined up exactly (more or less) in the same place as the word “solidarity” in the next film – and how political that was. I’m going to go out on a limb and guess that she is trying to say that it isn’t what is represented in a film that is political, but rather that experiencing a film (living through the experience of a film) might produce political effects on that film’s audience no matter what is or isn’t represented within the film itself. This was a position that seemed important to articulate for a while back in the ’70s, when some people were said to hold onto a crudely reductive notion about the relations between form and content in which content won out every time. It is impossible to find any of these people now, still willing to admit they ever took such a benighted position.

In compiling our programs we searched (high and low, mind you) for films that critically and/or actively represent resistance to power and the status quo, especially in the tone, shape, and manner of what is represented. Since in film it is nearly impossible not to represent something, it is, accordingly, almost pointless not to deliberately set out to take on the burden and opportunity of representation as a political act.

Today, when power so successfully exploits the apparent contradiction between terror and security as to scare off concerted resistance, the concentration of political, experimental film on the subject of history and the transformation of everyday life may be crucial. “Border-Crossers and Trouble-Makers” aimed to take up the question of the resistant subject both from the point of view of the history of oppositional film, and from current oppositional practices in film and video. Nobody is more conscious of the determining effects of the complex and ever-contested relations between what we still tend so crudely to denominate as form and content as the oppositional filmmaker. But in certain precincts of the art world that superannuated split between form and content is apparently still alive and kicking. According to Gronlund, “a presiding notion of documenta 12 … aimed to evoke in the viewer the fact of the migration of form and content across geographical boundaries and time, precisely by his or her own ambulatory migration through the gallery space.” You never can account for when people finally get the news, I guess, so keep on keepin’ on across the gallery space. I’m gonna go walk, that is, “migrate,” my dog.

– Melissa Gronlund

Footnotes

-

Roland Barthes, ‘Myth Today’, Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers), London: Vintage, 2000, p.145.

-

Ibid., p.146.

-

Roland Barthes, ‘Myth Today’, Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers), London: Vintage, 2000, p.145.

-

Roland Barthes, ‘Myth Today’, Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers), London: Vintage, 2000, p.145.

-

Ibid., p.146.