As an outcome of his commitment to Ukraine Bart De Baere noticed that the responses by both the Russian and the international art scene to the ethical questions raised by this ongoing disaster remain overall rather shallow. The present essay was written with the validity of the Ukrainian art scene as a core reference, reflecting from that perspective on the absence of an alternative ‘good Russia’ and of more consistent reflections in the international art scene. A Russian translation is published simultaneously in collaboration with the multilingual media platform syg.ma.

How to Go Forward

It is nearly impossible to think beyond the crisis the Russian Federation has caused between itself and Ukraine, so encompassing is the human suffering, the utter brutality of war and its impact on the international economy and geopolitics. Even in those spheres, it is hard to think beyond the reality of the total, limitless, hybrid war that is happening. Given its nature, culture might indicate more considerable possible orientations and perhaps even open up horizons. There cannot be an event too complex to be reflected upon in a nuanced way. An event of this magnitude might be expected to cause at least clear reflections on ethical positions to be taken from within the art field. Those have remained overall rather murky, scattered and incidental. This paper was written to reflect on that.

What becomes visible from the different positions as we move forward? How can we move forward? For some of the reflections on the current situation, it is not the right time yet, but at the same time, it is clear that possible futures will be grounded on what is being developed now. This paper attempts to bring together elements to help navigate this situation. It is partisan, written by someone with a deep involvement in the different regions existentially affected – Western Europe, Ukraine, the Russian Federation and Central Asia – and is a reflection on a crisis too close to us for us to have a true critical distance. It is not an essay per se, but rather a tentative preparation for what could become one. It doesn’t aspire to find answers but rather to draw a space, to open up questions, even if those cannot be resolved in any substantial degree in the here and now.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is not only a humanitarian, geopolitical and economic earthquake of the greatest magnitude, it is also a cultural catastrophe. The shifts arising from this dimension remained up to now largely unaddressed, even if that is what might be expected to be the prime focus of the international cultural field, that is, if culture is seen as being both about specificity and sustainability.

When the invasion happened, European cultural organisations were quick to set up temporary residencies for Ukrainian cultural workers, as a specific iteration of the broader hospitality to the refugee stream. They also considered help to Ukrainian colleagues, mainly focused on the evacuation of art works, which soon proved to be both unnecessary and also undesired by Ukraine itself. Since then, Ukrainian exhibitions have been programmed in several places, as if it were a fashionable thing to do.

On the one hand, relations to the Russian cultural scene were abruptely halted, and presentations of Russian art were limited and often caught in a mediatic game, with Ukrainian activists demanding their cessation. On the other hand, organisers have sometimes been arguing for culture as an essential space of its own, a space of free expression and one that is needed to build bridges. The invasion was also widely condemned in the cultural field, The invasion was also widely condemned in the cultural field, which beyond that then sometimes seemed to think only thing more sexy than presenting an Ukrainian artist would be to bring Ukrainian and Russian artists together. In the end all of these responses merely amount to variations on business as usual in a cultural field floating within a stream of mediatic gestures. What if it’s not about business and not about the usual? In that case both the situation and the consequences for the two cultural scenes and for the space containing their interrelation needs to be qualified, to deduce the strategic perspectives within them and therewith meaningful responses to them from the international art scene.

The Collapse of Many Things

When the Russian Federation invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022, it became immediately clear that this was more than an escalation of the war that had been ongoing for eight years. Rather, it obliged an immediate radical rethinking , in the here and now, . The invasion can be read along the lines of what the Lebanese artist and thinker Jalal Toufic coined as‘a surpassing disaster’. 01 This notion doesn’t only point to the withdrawal of what survived destruction and attempts of erasure, but also towards the activist duty in the slipstream of this, to either ‘resurrect what has been withdrawn’ or to ‘disclose the withdrawal’. Which withdrawals can be perceived, where might this status become a permanent one and what may be resurrected?

These questions pertain not only to Ukraine but also, and perhaps in the end even more so, to the Russian Federation. It is clear who set out for concerted erasure; the ‘first person’ of the Russian federation was assertive about his intentions behind this invasion, namely the erasure of Ukraine as a full-fledged country and culture. He declared it null and void. He coveted for it to be his property. President Putin still sees the whole of the Russian empire as essentially one and the same historical and spiritual space, and speaks about Ukraine as ‘our historical territories’, referencing Ukrainian back to ‘regional language peculiarities, resulting in the emergence of dialects’. 02 The Russian regime prefers for what it still calls ‘Little-Russians’ (Malorussians) to be of help to build a big common country governed from Moscow. And if not entirely so, Ukraine might at most remain a landlocked rump vasal territory, like present-day Belarus, its economic autonomy cancelled by Russia which took over its South-East. This is not only an incidental attempt in today’s invasion, Ukraine knows it is a plan that already existed in 2014, as propaganda from that period proves. 03

It is not yet clear who will be victorious. In this case the perpetrator may in the end very well be the loser, both factually in the physical war and in terms of the destruction suffered and the erasure afterwards. The physical havoc of this murder attempt at state level also encompassed two other killing fields, namely the space containing the Russian-Ukrainian relations and the identity of Russia itself. This article focusses on the last one, perhaps in the end the one most gruesomely affected, even if the mental reference point in the text is the position of the offended defender, Ukraine.

What can remain of the rich space of potential of Russian identity after this disaster? Major capacities of this were victimised just as well. The benign appearance of the neo-Russian empire was unmasked as fiction; the new tsar as a fake, who proves not to be a father at all. His very special operation turned the relational cultural diversity constitutive of original Eurasianism into uniform subjects that are primarily mass and cannon fodder. 04 The founder of Eurasianism, count Nikolay Trubetskoy, wanted to create a new imagination for the respectful cohabitation of diverse yet deeply related cultures, an imagination fundamentally different from both the Russian empire and the then recently founded USSR. Today relational diversity is not on the public agenda in Russia. Its future oriented, critical, inventive, open, diverse side was implicitly declared an enemy of the state and to a substantial degree explicitly labelled foreign agents.

As the catastrophe unrolls itself, the fable written by Alexander Etkind in late spring 2022 about the disintegration of the Russian Federation has become ever more of a realistic scenario. 05 This is the key nightmare of the present regime in Russia; it is ascribed by it to the evil thinking of the United States which it feels wants to further deconstruct the space of Russian influence in order to ‘divide and rule’. In real terms, history may very well prove that the demise of this space was a case of suicide. The present regime of the Russian Federation at this point advocates an aggressive neonationalism, without the mitigating circumstances of 19th century romanticism surrounding empires then, or the lofty rhetoric of the USSR. It uses a caricature of Eurasianism, the very opposite of its initial intentions, to dress itself up but in real terms doesn’t give a damn about that either. Indeed, it seems that the present Russian regime fails to make a viable offer to its peoples and subjects. It resorts to blunt and brute power. They may obey or may run away.

February 24th, the moment the disaster started to unfold, was not only a point of massive erasure, but also one in which other realities appeared on the centre stage. To start with, of course, there was the war to be reckoned with. Ukraine appeared as a victim entitled to unconditional help; as victims of mortal aggression, people and countries alike, should always get but all too often do not receive.

This sudden clarity of the urge to stand by Ukraine, also shed a devastating light on the overall complacency of the art scene and on the shallowness of the Western mindset, feeling hardly affected by catastrophes more than one border away. Even with regards to Ukraine, it remains to be seen how deep this feeling of proximity goes and whether it is not rather a response to a buffer zone being breached, whether it really is about compassion or about a mix of complicity and guilt and of a self-centred fear. Even so, it raises the question of how societal tragedies are being dealt with. Why was Ukraine entitled to all this attention while Afghanistan had been only a distant side show? What about Syria, that highly cultivated country in the Levant left to be largely annihilated over the past decade? What about the horror in Chechnya that brought president Putin to power? And what about the systemic Russian aggressions destabilising countries such as Georgia or Moldova? Even if only as ghosts to the invasion of Ukraine, they seemed to become a bit less absent in the public sphere than they had been when they started to happen. Also, the past aggressions of the Russian federation on Ukraine and its integrity which now appear painstakingly clear in light of how Ukraine itself has always understood them, that is non-negotiable. In this regard, the Western-European attempts at appeasement during the past eight years of war proved defunct.

The antagonism of the post World War II bipolar world order promptly re-emerged, now reduced to a regionalised scale, having shifted to the border between Ukraine and Russia. At the same time, in today’s multipolar world, the fringe of non-aligned countries of the bipolar epoch, reconfigured itself as a new majority of perspectives, the Global South now taking in its turn distanced yet informed positions. At the onset of the conflict, I took a day to find and read articles on Ukraine in Indian English-language newspapers, and besides reporting on arms trade, fossil fuel streams, geopolitical balances, stumbled up information regarding the consequences for India. It must enhance local political decision making to have such a broad field of public voices.

The Third Space of Loss

While it is clear that this invasion is an attempted murder on a country and this article aims to depict the situation to reflect on the self-inflicted havoc this created to the invading country, it should be noted that this is also paralleled by a third cultural killing field, namely of the space containing the relations between Ukraine and Russia. As put by Sergey Bratkov, an artist from Kharkiv, three days after the invasion while still living in Moscow and committed to his students at the Rodchenko School of Art: ‘Russia and Ukraine used to be called brother countries, but shit, no more’. The possibility to continue to live this imaginary was overnight mercilessly annihilated. ‘I can’t get out on the street anymore’, he added, ‘I can’t look these people in the face anymore’. A surpassing disaster may also render family relations obsolete.

That morning of February 24th, many of the remarks that might have been considered somewhat pertinent prior became utterly irrelevant. It is not only the Minsk agreements that were obliterated but also the attempts to accommodate Russian sensitivities of which those were the outcome.

Before the 24th attention might have been asked for the fact that Ukraine used to be part of a wider industrial system stretching over the border, but no more. Some Russian speaking Ukrainians might have felt a special proximity to Moscow, for a wide variety of reasons, perhaps simply from being part of the same transnational linguistic zone, but no more. On February 23rd it might still have been argued to be wise for Ukraine to translate its geo-cultural reality into a balanced international economic and political positioning. The morning after, this was simply out of the question. The dense historical and cultural fabric that until then seemed unbreakable was torn into pieces beyond repair. Also, the space for understanding Russia’s craving for Crimea obviously shifted too for those who had thought otherwise, Russia presenting itself bluntly as a neo-colonial power.

Despite their set up as two different countries, Ukraine and Russia still shared a lot of heritage and therewith potentially shared cultural capacity: religious, historical, and cultural backgrounds, but also people acting transnationally. For example musicians, singers, visual artists, television producers from Ukraine being popular in Russia. These connections might have rewired this relation over the years into a vast cultural dialogue that would give them both a mutually acknowledged place in each of the countries and as part of a wider transnational relational field. If such kinds of developments would now still be possible, this would not be first and foremost in the relation between Ukraine and Russia anymore, they might rather reappear in what seem to be at this point peripheric spaces, in the 22 non-Russian republics that are still part of the Russian Federation, or in the countries in the Caucasus and Central Asia that became independent between 1988 and 1991. In Kazakhstan, there is an interesting way of claiming Russian and mixed language. Between Ukraine and Russia such potentialities suddenly seemed to be vacuum sucked, with any breath of air taken out of them, through the binary logic imposed by the invasion. The immense Soviet sociocultural traditions are reduced to a source for wistful propaganda about a grand past on the Russian side, and caught by the present priority of anti-imperial thinking on the Ukrainian side.

And there is much more. For example, during the Russian empire, Ukraine was part of the Pale of Settlement where Jewish people could live. Or take the story of the Tatars who after Ukrainian independence could come back from internal exile to their native Crimea, to be once more persecuted when Russia took it over, a substantial amount of them then fleeing to Kherson. Horror, a lot of horror.

This third space of loss contains not only the relations between Ukraine and Russia but also that of more complex positions and the generative friction those may cause. Wars like this don’t only affect geopolitics and culture, but also people, victimised in different ways, and on other levels than that of the imminent horrors of war. In Yugoslavia, people could identify as Croat, Serb or Bosnian but also as Yugoslav. At the onset of the siege of Sarajevo a substantial amount of its inhabitants saw themselves as Yugoslav. Their country simply evaporated. Something comparable seems to happen now. In her brilliant, vulnerable text ‘Who May Speak’. the writer and artist Yevgenia Belorusets dwells not only upon the ‘dead empire’ that at present rules through violence, but also upon some of its outcomes, upon silence and the loss of ambiguity, grey areas, multiculturalism, voices, opportunities. 06 An early clear case in point has been that of the film director Sergei Loznitsa, identifying proactively as a Ukrainian, but opposing the boycott of Russian oppositional artists, advocating for a culturally diverse Ukraine, living in Berlin. A lot of media noise was made about him being expelled from an organisation naming itself ‘the Ukrainian Film Academy’ shortly after the invasion, for being a ‘cosmopolite’, opposing the boycott of Russian cinema. The war imposes monolithic nationalisms, albeit of a very different nature, in Ukraine by the popular will not to collapse, in Russia steered by an autocratic regime. When deciding to invade Ukraine, Putin also hampered the possibility to be publicly embedded through transnational self-identification or identities with a transnational component. A binary opposition took the upper hand, for the better and the worse.

A Need for Both Suspension and Action

In this binary set up one of the two components went catatonic. Another obvious outcome of this disaster was that the cultural relations between Russia and the rest of the world had to be reset and therefore suspended. On a personal note, the author of this text immediately resigned from the board of the Russian Pavilion in Venice, stating that this was the only advice to be given then. Some of the board members still felt that the intrinsic value of the presentation might be somehow continued, but the artists and organisers luckily understood this was not to be the case. The field of cultural relationality between Russia and the world was reduced to a catatonic state by the monomaniac attitude from its state and institutions. The emptiness of the Russian pavilion was therefore the only valid expression possible at that moment in time.

On an institutional note, the museum the author directs, M HKA in Antwerp, tried to help straighten out the confusion in the cultural field. With the museum confederation it is part of, L’Internationale, it advocated for an immediate cessation of interactions not only with state institutions but also institutions with close ties to the regime, and obviously to private foundations for contemporary art. 07 For M HKA especially this was a major decision, given its partnerships with V-A-C Foundation and, to a lesser extent, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art. 08 Suspension of the relations all the same seemed to be the only valid possibility; the possibility to discuss intrinsic values and possible futures was grotesquely annihilated by the disaster.

At the same time urgencies appeared on the other side of the divide, through the urge for actions towards Ukraine. There too, M HKA found itself in a special situation, and not only because of its proximity to Brussels, the centre of both the European Community and NATO. With its Eurasian perspective M HKA had over the past decade also been giving a consistent attention to the vital, internationally undervalued Ukrainian art scene and holds a Ukrainian collection. It could therefore immediately not only take the widely taken steps of publicly taking position against the invasion, and giving humanitarian help to refugees and institutional help to the art scene in Ukraine, it was also in the position to aim beyond this immediacy.

In an intense partnership with the PinchukArtCentre, the leading Ukrainian contemporary art institution, and its artistic director Björn Geldhof, it tried to help on two fronts – which we may also see as limits – other than the immediate priorities. 09

One of these fronts is an astonishing situation. The upsurge of a desire to help a country in need, a country suddenly felt to be a close neighbour, went in western Europe hand in hand with a virtual absence of knowledge about that country and of real relations with it. The other limit was the immediate reduction of this upsurge of sympathy to the sectors of military, financial and humanitarian help, as if Ukraine were effectively null and void beyond these aspects – as president Putin wanted to have it.

With regards to both limits, the partnership between M HKA and PinchukArtCentre generated an analysis beyond the moment, and undertook projects that may seem almost spectacular in their outcome, but that are actually only drops in the oceans of these two mid-to-long-term challenges. Addressing the first limit the partnership succeeded in making three parallel exhibitions, at M HKA, at the important Centre for Fine Arts Bozar in Brussels, and at the European Parliament itself, under the patronage of no one else than the president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

The second limit is that of Ukraine as a country. It is indeed a country at war but it is also much more than a war zone, which the partnership addressed through the reopening of the PinchukArtCentre last summer in Kyiv. It did so with an exhibition that was based on an international selection of works from the M HKA collection, brought into conversation with works by Ukrainian artists to form spaces for thinking. The exhibition also integrated the Davos ‘Russian War Crimes’ exhibition, as an unavoidable reference, a wailing wall of sorts, to be both addressed and lived with. The risks of war and terrorism were here obviously real and as always not covered by art insurance. M HKA succeeded in convincing the Flemish minister-president to formally assume these risks to this Flemish public cultural heritage as a sign of effective solidarity, a willingness to have a dialogue and of capacity sharing with Ukraine.

However meaningful, these actions in the cultural field are at best the beginning of vast urgencies that will have to be addressed on a massive scale. When visiting Hostomel and its airport in the early summer, its military commander also showed us the humanitarian aid he was distributing, saying ‘this is a road to nowhere’. He pointed out that before the war Hostomel was also home to the largest glass factory in Ukraine, with three hundred employees. On 6 September 2022 President Zelenskyy rang the opening bell at the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), to celebrate the launch of Advantage Ukraine an initiative aimed at finding four hundred billion dollars of foreign direct investment in Ukraine. 10

How to Proceed

The capacity of the international cultural field is clearly limited if it is depicted within the scale of the havoc caused by the Russian invasion and the resulting war. The most immediate priority is indeed massive military help, the second massive financial assistance. Culture may play, all the same, a valid role in such a situation, as has been proven during the siege of Sarajevo when cultural activities became a symbol of the vitality of the city. The international cultural field may enhance this role by developing relations with the Ukrainian cultural scene. It will then unavoidably also have to address its future stance towards Russian cultural actors and towards the relation between Ukrainian and Russian culture. These are three different points of attention.

Within Ukraine there has been an outspoken tendency to a ‘cancel Russia’ stance. This demand for a boycott is understandable and it is a valid cultural strategic possibility. It was earlier on successfully applied against the South-African apartheid regime. In that case it didn’t apply, however, to ANC supporters. Such an action is always qualified; it is not against a country and all of its people, but may be against a regime and all of its supporters, including the people that tolerate or passively support it.

Obviously then, it might now target everyone not explicitly distancing from this regime, but the real question is that of the qualifiers that are expected in a positive, future-oriented sense.

A different question, only seemingly related, is the refusal by Ukrainian actors to work together with their Russian counterparts, however ethically astute those might be. At this very point in time that automatically brings along the question of the coupling of the two countries, it is at the same moment a no go from the Ukrainian side.

This plea from Ukraine to disconnect from inquiries into a relation between Ukraine and Russia is obvious, or ought to be so. When Björn Geldhof and myself were invited to advise the European Cultural Commission on Ukraine in late spring 2022, the Ukrainian representatives made an astonishingly serene request for such an uncoupling during the meeting. This plea was immediately overruled by a member of parliament who felt she had to advocate there and then for the principle of free expression and therewith for the right of Russian culture to continue. This felt offensive.

It is offensive because in the case of a crime it is first and foremost the victim that needs to be heard and cared for. It is up to the raped to decide whether – and if so how – to have to confront or even discuss the rapist. Also, in the time to come it will be up to Ukraine to decide when, and to which extent, this matter can be put on the agenda. It will then for certain still not be topic number one, as conversations on anti-imperialism and decolonisation, amongst others, will most certainly get a higher priority.

In terms of actual cultural practice nowadays, when organisers want to involve Ukrainians and Russians together at the same time, the minimum minimorum ought to be that they inquire with the Ukrainian actors that they consider whether they would be willing to accept this and if so, what their conditions would be, prior to any invitation. Only after that could they decide whether and how to go ahead with the initiative. All too often, in the months after the disaster the opposite has been the case. Western thinking still tends to project its own position on any given situation, rather than aiming to get insight in the complexity of a situation to gain understanding. Western Europeans especially in this case tend to prioritise their own pet attitudes, being proud if they succeed in bringing Ukrainians and ‘good Russians’ together. Ukrainian curator Vasyl Cherepanyn calls this self-centred feeling of justness a ‘petty-bourgeois ideology’; it is the outcome of a pacifism that is merely a comfortable fetish. 11

While each of the three perspectives are interrelated and each need to be addressed towards the future – what with Ukraine, what with Russia, what with the space containing the relation between them – they now need to be addressed as rigorously separated.

The real prime ‘null and void’ is here the present state of the space of relationality between Ukraine and Russia. It is the core of the surpassing disaster of the invasion. Ukraine has after this invasion an obvious right to refuse the positive potential of relationality between itself and Russia. The way forward for this question is therefore relatively simple: not now.

On the other hand international institutions may all the same want to continue to work with some artists coming from Russia. If they are serious about their support towards Ukraine, they will then not see this as business as usual but as a decision to be actively addressed and reflected on. They may then include reflections from the Ukrainian side to enhance their own awareness. Even if international institutions don’t follow the plea of the Ukrainian minister of culture ‘to pause performances of Kremlin-favoured works’ they may all the same then still make clear they heard him all the same. 12 Canonical Russian art may at this point in time want to be accompanied by a critical analysis of its position and of the degree to which it implicitly or explicitly endorsed empire.

Such conscious ways of acting might gradually open up a space again for works from the Russian cultural sphere not favoured by the Kremlin. Analysing, situating, qualifying. Such punctual, precise arguments may then gradually add up to broader lines of understanding. The disaster imposed a politicisation on the sphere of Russian culture which is comparable to the economisation that befell to visual art internationally since the 1980s. Both the political and the economic dimension are not the core but always implicitly present in all culture. They may take the upper hand in societal terms which means that they then become a translation mechanism for intrinsic qualities, a lens that formats perception.

Such a lens was now added to the perception of Russian art. The critical reflection needed to address this is of a different nature than that of the request to simply speak out ‘against the present regime’ or stand up ‘against the war’. Ukrainian thinking may value such statements but nevertheless remain unconvinced. It will want to refer back to the past decades and to the accommodation of both the regime and its wars during that period. Ukrainian criticality relates to systemic questions. Inviting Russian artists on the positive note that they are against the current regime or against the ongoing war might become a new version of maintaining the status quo. What, then, do such notes really mean?

The key question here may be that of a shared responsibility taken up by people identifying with the sphere of Russian culture. That sphere is now challenged to not only generate a self-criticism and renew its self-awareness, but also to conceive of ways forward.

Learning from Ukraine

The present resistance by Ukraine is an outstanding example of collective responsibility being cultivated. This is a deeply cultural fight, Ukrainians not wanting to be categorised as Malorussians. The country presents the astonishing phenomenon of a president whom in the heat of war took time to decide to patronize art exhibitions and to appear online not only for his people and in main political cenacles, but also during cultural events. He gave speeches for the Cannes and Venice film festivals and during the Grammy Award Ceremony, as well as to American, Australian, Canadian and French university students. During one of his addresses to his own people he focused on the destruction of the museum in the Kharkiv region dedicated to the 18th century Ukrainian philosopher Hryhorii Skovoroda. 10 While these actions may be cynically explained as highly effective propaganda by a media-savvy person, they are even then testimony to more than that. Zelenskyy attaches key importance to art: ‘There are no tyrannies that would not try to limit art, because they can see the power of art. Art can tell the world things that cannot be shared otherwise. It is art that conveys feelings’, he stated. 11

Notwithstanding his brilliance, it has to be clear that Zelenskyy is not the origin but an outcome of a collective endeavour. The Ukrainian people have not only modelled their state through the ‘Orange’ and ‘Maidan’ revolutions, but they also activated a sturdy cultural reference frame for it. If Zelenskyy would ever show autocratic tendencies, they will get rid of him too. The present Ukrainian banknotes feature besides Skovoroda – with his challenging thinking about equality –, two hetmans of the Zaporozhian Host, a long-lasting Cossack political entity with a parliamentary system of government. And perhaps even more importantly, they include three 19th century emancipatory poets: Lesya Ukrainka, also a feminist and activist; Ivan Franko, after whom the university of Lviv is named, also a critic, economist, activist and philosopher; and Taras Shevchenko, after whom the Kyiv university is named, also a visual artist, political figure and ethnographer. Since Maidan the Ukrainian artistic and intellectual community has been thematising its cultural tradition as a progressive capacity, as shown in an exemplary way in the work of David Chichkan. 12

The Ukrainian artists have been deeply committed to the war effort. When Alevtina Kakhidze received German support with explicitly no strings attached, she decided to donate it to a crowd funding campaign for a drone for a friend of hers that had volunteered in the army. The peloton of that friend therewith became a peloton with a drone, a vital advantage. Likewise the artist Zhanna Khadyrova has been spending the entire gains of her successful ‘Palianytsia’ series on supporting the army, having bought by the summer of 2022 already over a dozen second hand cars for army units of her neighbours and friends to be used for logistics. Those may sound like astonishing deeds but what these artists do is actually quite normal, they are merely part of a society of a country that is fighting for its existence and where enterprises buy additional body armour and equipment for their employees in the war, neighbours for their neighbours, friends for their friends, in a broad bottom-up commitment.

Artists have been quite reflective on how to support the collective effort and the role they may play in it. In an online Q&A at M HKA in May 2022, Nikita Kadan described how the situation requires to accept the very opposite of what civil society in Ukraine aims for, namely for progressive and democratic tendencies to dominate its society. 13 ‘The war requires a unity of command, everyone needs to follow this now to succeed’. He was positive about the future: ‘I don’t see the shadows of a new xenophobic nationalism, I see people in struggle for survival. It means that they are more realistic than ever. Extreme right-wing politics always uses irrationalism, strong collective illusions. And Ukraine now is very different. Ukraine is really disillusioned’. When asked about how this radical collective effort under one command might be paired with the criticality that is one of the main features of contemporary Ukrainian art, he compared the situation to being under water, criticality being oxygen, wondering how long one can survive without it.

The Ukrainian artists of this generation were to a large extent formed by Maidan or even took part in it, undertaking actions in the streets, being on the square when demonstrators were shot. The most compelling image of Maidan is by Oleksandr Burlaka, taken on the turning moment of 22 February 2014, of a police blockade confronting demonstrators, and in the air a stun grenade, a cobblestone but also a rainbow that is actually the outcome of the water cannons being activated.

The criticality the Ukrainian art scene has developed over the years in the peculiar and intense circumstances it had to deal with, is the opposite of a declarative political stance. It is grounded in a keen interest in proper artistic capacity. Lesia Khomenko’s paintings present an astonishing array of proposals about how images may be tweaked. She does not only reflect on how soldiers may be represented – including her husband who is a volunteer in the Territorial defence forces and even members of his peloton group to start with –, but she also translates questions on the technological military gaze as well as the effacing of detailed information in social media posts, pictorially. Danylo Galkin links his reflections about Soviet cultural heritage to those about the recent condition in his grisaille paintings of stained-glass windows. Alevtina Kakhidze continuously energises the fluid nature of her imaginary through the reflections of the cultural and political impulses that present themselves.

They combine a shifting topical criticality in their subject matters with a visual astuteness that focus their works unto reflective capacity. Anna Zvyagintseva may at one point depict fragile moments of homely intimacy, and at another put the audio recordings of conflicting demonstrations into a high-pressure cooking pot. Nikita Kadan transcends both his initial painterly interests and the collective performative actions he was part of in the slipstream of Maidan, into a field of complex reflections about the cultural setting of his country, linking up precise historical references, plants and remnants of rockets into innovative installations. The artist duo Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei posed in a new work as dead Russian soldiers in five pictorial LED videos, the outcome of a reflection of how the German romantic tradition, still influential in Russia, detaches high sentiments from the real.

These artists have not only deeply committed to the war effort, at the same time they continue to present a vision of art as categorically autonomous from both the economy and from the socio-political consensus. At the same time this autonomy always links back to their experience of reality, it re-emerges over and again from a commitment to it. It is never separated from it as ‘art for art’s sake’, but is driven forward by the urgencies within their society. This is a joyful state of mind, not devoid of humour, that allows one to tackle topics as a matter of fact. It makes diverse modes of activism not a prerequisite but neither an abnormality. It is part of a courage that is expected in and on behalf of the public sphere. The Ukrainian ethos is holistic, with a vision of art as an integral, autonomous yet responsible domain. One might name this a constructive criticality.

Ukraine for certain may have a proper artistic capacity but it has also cultural priorities that ought to be shared proactively by the international cultural scene. It is then insufficient to become aware of the fact that Kasimir Malevich was born in Kyiv and that a substantial amount of the early avant-garde is indeed Ukrainian. The Ukrainian art scene has to establish its own narrative and this on an international level. This priority amongst others has to be able to develop the consequences of the decolonisation that comes after empire. It is obvious that international institutions have to take part in this, not only to support Ukraine but also simply because it is a responsibility they have to take up on their own behalf. Some institutions have effectively started to work on this. 14 This is in the end a more substantial support than that of inviting Ukrainian artists and curators as residents because they are refugees.

It is possible to learn from Ukraine but from its perspective that is not the optimal relation. A better way to go forward for the international art field in this case may be the notion of capacity sharing. The Ukrainian artistic capacity and cultural priorities may then become a shared challenge, to be both embedded in and enhanced by international reflection.

Russia Revisited

‘If everyone in the world had at least ten percent of the courage that we Ukrainians have, there would be no danger to international law at all. There would be no danger to the freedom of the nations. We will spread our courage. We will start a special global campaign. We will teach the world to be not just a little bit, but full of courage. Like us, like Ukrainians’, stated Zelenskyy in one of his speeches. 15

The Ukrainian art scene does respect the 2021-22 Belarussian attempt at revolt but I didn’t hear a convincing analysis of why it failed. The best guess I heard came from artist Oleksiy Say, ‘perhaps they were too polite’, referring to a demonstrator whom first covered a park bench before standing on it. The Ukrainian art scene at large reproaches the Russian art scene at large to have been insufficiently brave, not to say complacent and cowardly, both in the past and in the present.

Russia has for a very long time been a space where the public contract included abstention from political activity. In more focused terms: within art anything could be addressed, in more or less overt ways, except criticism on the ‘first person’. In more or less overt ways; the closer a topic came to the political, the more sensitive it was considered to be. The setup was therefore to a substantial degree about accommodation and compromise, a game of positions. Like so many situations all over the world yet specific.

The 20.000 cultural workers that initially signed the Open Letter of Russian Culture and Art Professionals, were well aware this might endanger their position. 16 Since then the situation became worse, the Russian Laws Establishing War Censorship and Prohibiting Anti-War Statements and Calls for Sanctions approved in March 2022 sentences up to fifteen years in prison. It is less obvious what to do when having only one shot before potentially being taken out. If this is your perception, when then to use that, and to what effect?

In the beginning of October 2022 Dmitry Ozerkov, from the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, announced that he left the institution. He wrote ‘As a Russian citizen I saw this shame as my own fault too […] my choice was to stop doing anything in and for today’s Russia’, a negative choice but even more importantly one that is self-critical. He ended his Instagram message ‘I salute all for whom the Greek word Exodus, used by the writers of the Septuagint, has become the only possible way out of the current situation. Russia squeezed out all of us who wanted nothing but good to its culture’.17

Not only those people who used to have a transnational sense of self identity anchored in the space of Ukrainian-Russian relations lost their ground when the invasion started, also those Russian actors who had been working for an open, diverse country, held together by encounters between people with multiple identities, lost that country all of a sudden. And the deeper they were committed to it, the more profound was their loss. This civil war was never waged, but they lost it all the same. The remnants of that Russia are scattered at this point in time, partially inside the country, partially outside of it. It seems that all actions that can be undertaken, amount to partisan activity of a lost party. But is this truly unavoidably so?

Does the Russian world, the ‘Mir’ that encompasses both the real community of the village, the world at large and the notion of peace, necessarily have to continue to be equal to the territorial space of the Russian state as the present regime wants to continue to have it? Can that Mir not become different communities, one perhaps indeed still governed by the regime, the other one existing as transnational networks of reflective relations? Can Russian cultural actors that migrated only survive by being absorbed in other localised situations or can they also in their capacity of Russian actors add to both those and to their own background? Can they also somehow form a second Russia? Can this withdrawal be followed by a resurrection of sorts, even if only as an imagined space, imagined yet real in terms of cultural endeavour? It is surprising that there is as yet no organised Russian public alternative space, the more so given the fact that so many of its potent cultural actors are now living abroad.

Who may speak? Who may remain silent? Yevgenia Belorusets points out how a disaster may affect these capacities and how it makes speech acts contingent upon how a speech may succeed to stage itself. This is at this point in time certainly also the case for Russian actors.

Even the most moderate Ukrainian will want their positioning to be outspoken and public. There may be reasons not to do so all the same, better reasons and lesser ones, existential ones and shallow ones. On the most shallow side there is mere survivalist accommodation, as became visible in the rightful discussion on the Tzvetnik group.18 The defunct Russian social contract stimulated in the past an unreflective opportunism and it now hinders the recalibration of positions. It gives the impression that the choice is between exodus and an action at the best possible moment that may then well be the only shot. If one is used to go with the flow and navigate on the base of risk analysis one may be at loss when the flow ceases and any move suddenly proves to be risky one way or another. Situational thinking is in itself a quality, but only if it continues to follow an ethical compass.

For many actors choices have been complicated by practicalities that are quite existential all the same. There may be family to take care of or other responsibilities still considered key. Some of the museum directors who stay on safeguarded their staff that signed petitions, others fired them. In the future this difference might be noted. On the other hand, the alternative path of migrating has not been obvious at all, having to leave in this case with hardly any or no money and towards a world tending to be hostile to Russians. Leaving your country is anyhow not their first option for most people. Becoming an émigré in this case seems to mean losing it. Beside all of these practical considerations, people may hope for a different future for their country still, even if they don’t yet see viable proactive strategies in the present. Many of the artists from Russia initially simply cancelled their exhibitions and ceased working. This Innere Emigration, as it was once called in former East Germany, is an understandable initial response. But then, an active awareness to specific situations will follow other paths if it considers some impossible.

It has to be noted that several Russian artists did make clear statements about the war; some of them took an active part in the anti-war protests,19 prohibited the continuation of exhibiting their works that are in Russian collections, 20 donated the income of their art to helping Ukrainian refugees21 or even actively supported the Ukrainian military.22

Neither being ‘against the war’, nor being ‘against the regime’ are in themselves positions, and neither is migration. The massive exodus of artists and cultural workers is a sign but its meaning is blurred.

Migrating, being against the present war or being against the present Russian regime may be valid anchoring points for further action but the key strategic challenge of the Russian cultural sphere, and therewith of its actors, is beyond those statements. It is to finds ways to respond to the politicisation that was imposed by the disaster. The lens of the political dimension that all of a sudden became an interface for Russian art, is a shared responsibility that incites anyone self-identifying with this sphere to express in one way or another their sense of individual responsibility, acknowledgement and awareness. Whatever the future will be, it is made now.

All art intrinsically has a political capacity. Any artistic position has to articulate its space in order to appear, and at this point in time that means to stage itself in relation to a background of both real war and real commitment to the human world. Actors from Russia may at present find it hard to find an outcome, because many of their habitual spaces have been vacuum sucked. Outcomes are required, though, because time will tell, time will ask justification. Avoiding public stance is also a position, and now comes with a burden. Also silence can and needs to be conscious and articulated, now quasi required to be outspoken.

The artist Evgeny Antufiev is an example of how this can be taken up. He has been outspoken, pubishing an artistic statement beginning with ‘this war must be stopped, this war is a crime, the criminals should be prosecuted.’ 23 In the text he addresses what seems to be at this point one of the main limits of the Russian artistic mindset:‘Our artistic language is hardly suitable for talking about war and violence. We work with materials, symbols and memory. Yet art exists within the context of its time. Especially during the war, especially in the aggressor country. Unable to find artistic means to talk about the present, we turn to the past. Violence does not appear out of nowhere: it is the echo of other violence.’ The limit he addresses is especially pertinent to the largely depoliticised contemporary art scene in Russia, often evacuating the here and now or indirectly amending the official narrative through microhistories.

Antufiev, still living in Russia, starts his statement with ‘First of all, we have to answer certain questions. How has the Russian army ended up in Ukraine? Why is the totalitarian aesthetics popular again in my country? Why have voices that have long been silent reappeared from the void? I don’t know how to answer these questions with art.’ 24 He does bring building blocks for an answer, all the same. His exhibition in Emalin in London made together with his wife, Lyubov Nalogina, starts from pieces of archive he acquired of Marshal A. A. Grechko, the Minister of Defence of the USSR until 1976, whom advocated to accelerate the deployment of nuclear weapons and led the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. 25 The exhibition thematises both this last feat and his hunting hobby, featuring also Grechko’s huntsmen and their prey.

Examples such as this remain as yet individual cases. Speaking in terms of a political imaginary, how come there are no protests before Russian embassies by the now huge Russian migrant community, speaking in terms of a cultural imaginary, how come there is no ‘good Russia’ declaring the present regime null and void?

In the same way as immediate, outspoken statements of actors towards the invasion and the regime that unleashed it may only be an initial representation of the articulation of the political dimension of their art, immediate reflections about the catastrophe and its causes may be part of, but don’t equal, the strategic challenge of the sphere of Russian culture. It will have to set out in the coming years a process alike the one in post-Nazi Germany and it can only do so itself, it may as part of that also want to address the question of shared guilt, but its strategic challenge is essentially about offering capacity. It may just as well put forth values it considers important, as the V-A-C program aborted by the invasion planned to do. 26The challenge will in the end be still more about how to go from the present to the future, then about how to understand the present limits from the past onwards. The present exodus did not yet seem to lead yet to even the beginnings of a vision like that of the migrant community from the Russian empire after the civil war a hundred years ago. 27 Basic questions such as those of Antufiev are still heard too rarely from the Russian side that owns them, as are the beginnings of possible answers such as his. Mere survival still seems to be the main priority even for the huge migrant Russian cultural community. Most probably it develops reflections in its own language sphere, as was also the case in the 1920s. It would then be good that those reach out.

Their most critical address will in the end be towards Ukraine. Russia at large may learn from Ukraine, and then, just to start with, it will have to learn to fully acknowledge it, take a step back, and listen to it. Actors will also have to recalibrate their relation towards the international cultural field. That may be a double bind. The international field can in any case go beyond mere mediatic indicators such as ‘no war for me too’, be more deeply attentive and critically reassess Russian artistic positions, as an intensified mode of its continuous overall practice. Which means that if engagements are taken they are argued, thus stimulating and validating the precision of these positions and the artists committed to. It can be critical and self-critical towards this complex.

How Not to Conclude

Reductive blaming is nearly as evil as evil itself. The Russian army in Ukraine has been behaving in bestial ways, but it is too easy to therefore declare Russian culture essentially bestial. Relevant questions are more specific. Indeed, how did the Russian army end up in Ukraine, or why it came to structurally use terrorism and genocide as a tool of war on the people it considers its own.

Reductive blaming hinders reflection. Reflection mirrors questions back to one’s own situation. Perhaps Vladimir Putin can be perceived to some extent as an exponent of the epoch of The Wolf of Wall Street, an epoch of cold cynicism that considers any tool valid for any result desired, making utter abstraction of people. An epoch of greed, hunger for power, self-indulgence, self-centredness. In his surgical analysis of the construction of the neoliberal utopia as expressed in Ayn Rands’s Atlas Shrugged (1957), the Dutch theologian and philosopher Hans Achterhuis starts from the observation that this implies the negation of one of the ten commandments: ‘Central on the second table, arranging the interhuman commandments, was written: “Thou shalt not covet.” According to many interpreters we are dealing here with the primordial commandment that makes a human society possible.’ 28 Each and every reproach to be made to the present regime of the Russian Federation and its first person can be easily mirrored into a multitude of events in our own societies, in diverse segments and on all of their scales. Criticising the underlying drives that propel it and him comes fairly close to reflecting on the eternal limits of mankind.

The strategic questions for Russian society lay on a lower, more concrete level: how did its setup – its culture, that is – allow for this to happen here? How come the Russian people didn’t go into a version of Ghandian Satyagraha or into a Ukrainian style revolution? What were limits in this set up? Which strengths proved to be weaknesses? What might have been done beforehand and what might be done in the future? What might be resurrected and what ought to be withdrawn? Our contemporary sense of relativity, also in its positive twist of relatedness, makes us aware of the fact that these questions are owned by the Russian people and by its cultural sphere.

By being expectant and attentive to proposals in this sense we might be able to learn from Russia, not merely to recalibrate our image of its capacity but also to enhance our own sense of self. Indeed, not only the Russian first person’s behaviour but also that of his people is all too familiar. Complacency and evacuation are not alien to our own environments, they flourish. The noosphere defined by the Russian-Ukrainian Soviet biogeochemist Vladimir Vernadsky – featured on the highest Ukrainian banknote of 1000 Hrivna – as the planetary ‘sphere of reason’ that for him the last state of biospheric development, seems to be overgrown these days by both primal emotions and surface effects.

We set out in the beginning of the 20th century, across the diverse ideologies then present, to educate all people, in order to turn them into active citizens. After World War II the different versions of the welfare state in east and west, north and south, each promised a better and lavish world, continuing all the same that function of social action and furthering the emancipatory drive.29 Yet here we are, now, at loss. How come we seem to be unable to get out of the mediatic stream geared to instantaneous superficial visibility? How come we failed to collectively formulate a more holistic, compelling, challenging response to the surpassing disaster that happened to Ukraine? Where and when did we lose track?

Perhaps this is merely one more result of an overall development towards hyper specialisation, a tendency of focus in order to be more effective that also leads in the end to actions detached from the wider world, geared at output, and therewith ultimately at effects. In the space of reflections around art this kind of development might then be represented by the post-structuralist critique, leading at the same time to powerful insights by the specialists and to disempowerment of the non-specialists.

Art as a tradition is at odds with this. As a tradition it is rather the visual equivalent of organic intellectualism, aspiring to be accessible, at the same time precise and holistic. It doesn’t necessarily have to address each and every problem in the world but it may always be considered to imply a stance towards them, a stance that may be rendered explicit if need be. It is grounded in specific contexts but as a tradition always aspired also to transcend these contexts. It is considered a space of awareness and reflection, to be continued.

The art scene that is its caretaker might therefore be expected to activate its critical capacity at moments when a surpassing disaster appears to happen. Not only to analyse what is withdrawing and to reflect on what might be resurrected in the eye of the storm but also as a mirror to ask the same questions on the other side of our shared reality, and to find out which capacities may be shared.

Ukraine may not have to teach the world courage, but in the best developments after the best outcome of the present war its civil society may become a valid partner to discuss how to collectively enact the values of a society. The constructive criticality of Ukrainian art may then be part of that conversation.

Antwerp, 24 December 2022.

Footnotes

-

Jalal Toufic, The Withdrawal of Tradition Past a Surpassing Disaster, Los Angeles, California Institute of the Arts/Roy and Edna Disney/CalArts Theater [REDCAT] and Forthcoming Books, 2009.

-

Vladimir Putin, ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’, available at: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181.

-

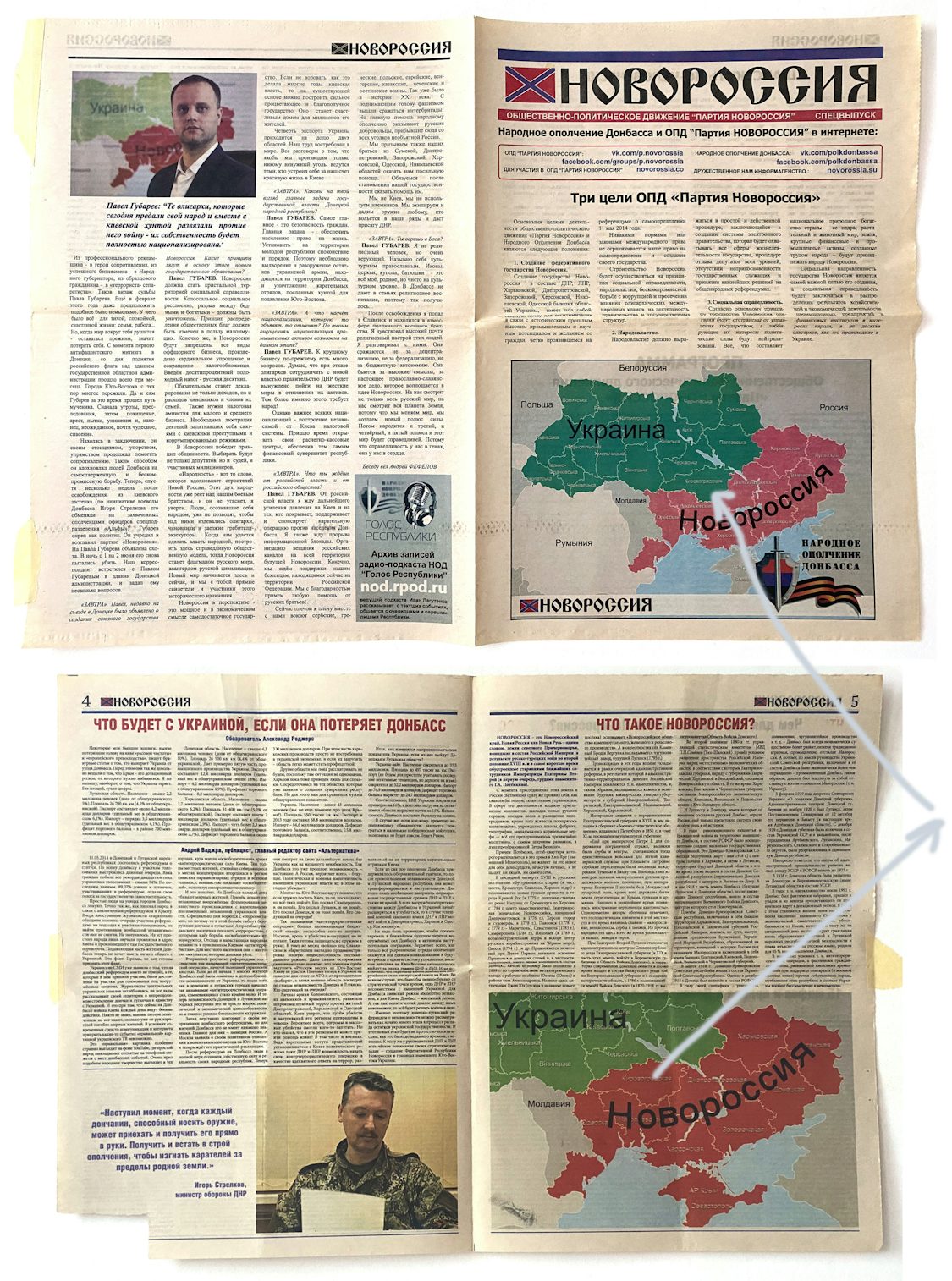

Archive of Alevtina Kakhidze. Propaganda brought to her by her mother living in the occupied part of Donbas, initially brought to the artist as waste paper recycled to wrap vegetable and fruit glass jars.

-

Bart De Baere, ‘Eurasia as an Island’, in Bart De Baere, Defne Ayas and Nicolaus Schafhausen (ed.), Main Project—6th Moscow Biennial, 2015, pp.49–85.

-

Alexander Etkind, ‘The Future Defederation of Russia. All empires eventually fall apart. The Russian Federation is next’, The Moscow Times [online], available at: https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2022/06/08/the-future-defederation-of-russia-a77934.

-

Yevgenia Belorusets, ‘The War Diary of Yevgenia Belorusets’, available at: https://www.isolarii.com/kyiv.

-

Art world – oppose Russia’s invasion of Ukraine! [online petition], available at: https://www.change.org/p/art-world-art-world-oppose-russia-s-invasion-of-ukraine?fbclid=IwAR3-wcbKxGBM7D1FzTMG1RkkAPkX_CciaxNqIUk6sibNKT0WvjAVK9b6CcA.

-

Garage Museum did immediately make a clear statement. See ‘Announcement from Garage in the light of current events’, 26 February 2022, available at: https://garagemca.org/en/news/2022-02-26-announcement-from-garage-in-the-light-of-current-events.

-

Imagine Ukraine [website], avaiblat at: www.imagineukraine.eu.

-

‘A missile. To destroy the museum. Museum of the philosopher and poet who lived in the XVIII century. Who taught people what a true Christian attitude to life is and how a person can get to know himself. Well, it seems that this is a terrible danger for modern Russia – museums, the Christian attitude to life and people’s self-knowledge’. Volodymyr Zelenskyy, ‘Evil returns when human rights and the law are violated and culture is destroyed; this is exactly what happened to Russia – address by the President of Ukraine’, 7 May 2022, available at: https://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/zlo-povertayetsya-koli-znevazhayut-prava-lyudej-zakon-i-rujn-74881.

-

Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Opening of This is Ukraine: Defending Freedom, 21 April 2022, Scuola Grande della Misericordia, Venice.

-

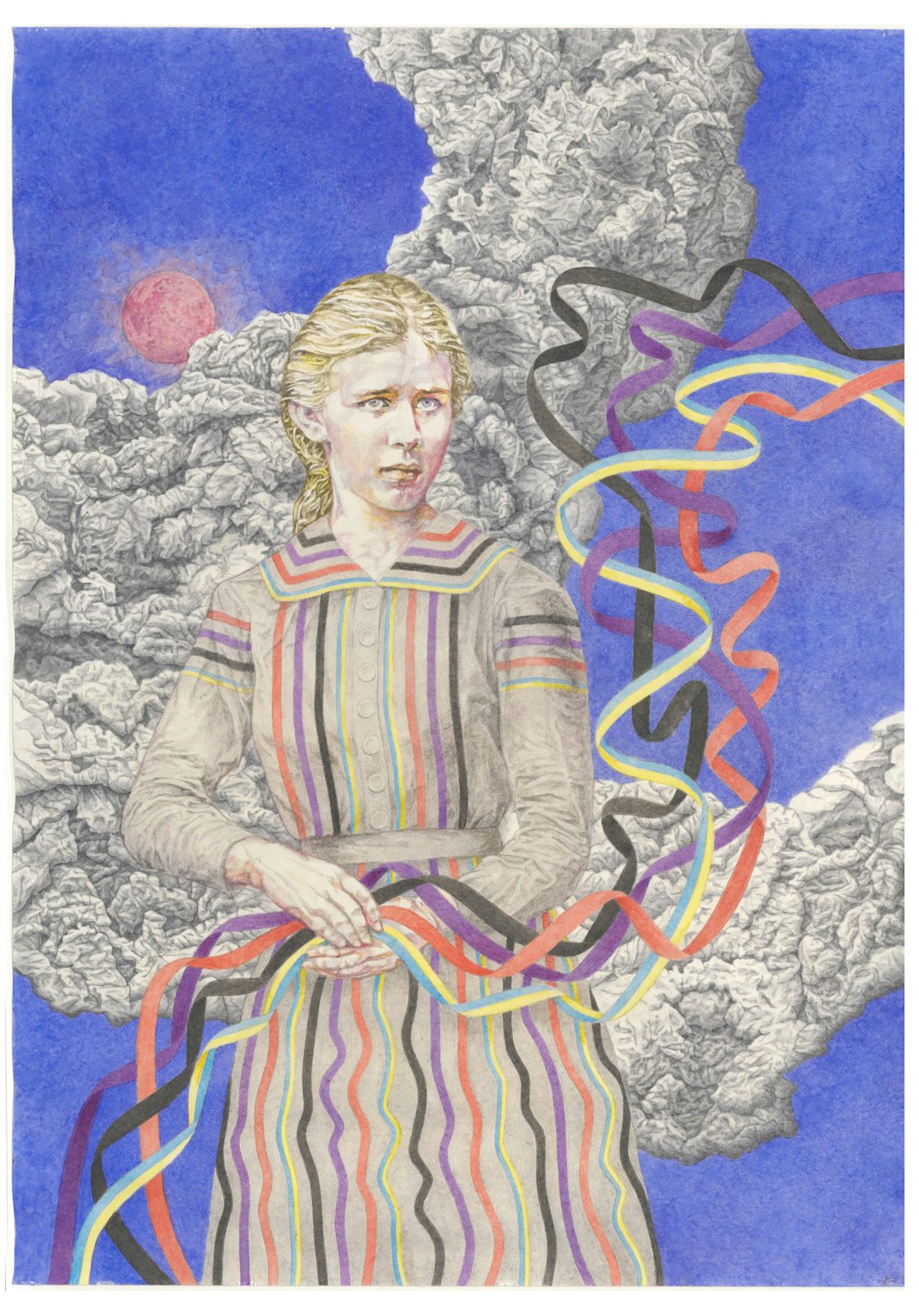

Davyd Chychkan, ‘Ribbons and Triangles’, M HKA Ensembles [online], available at: http://ensembles.org/items/32160.

-

Nikita Kadan, ‘Online Q&A with Nikita Kadan’ as part of ‘How to Imagine a Country’, 5 May 2022,M HKA, Antwerp.

-

‘HERE AND NOW at Museum Ludwig: Modernism in Ukraine & Darya Koltsova’, 3 June–24 September 2023, Museum Ludwig, Cologne.

-

Volodymyr Zelenskyy, ‘Being brave is our brand; we will spread our courage in the world – address by President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’, 7 April 2022, available at: https://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/buti-smilivimi-ce-nash-brend-budemo-poshiryuvati-nashu-smili-74165.

-

Russian Cultural and Art Workers, ‘An Open Letter from Russian Cultural and Art Workers Against the War with Ukraine’, New Politics [online], 24 February 2022, available at: https://newpol.org/an-open-letter-from-russian-cultural-and-art-workers-against-the-war-with-ukraine/.

-

Dimitri Ozerkov, [Instagram Post], 2 October 2022, available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CjNdf6lMxRH/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link.

-

Zuzanna Czebatul, [Instagram Post], 16 October 2022, available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CjyATkNoWC1/?igshid=NmNmNjAwNzg%3D.

-

Such as the collective ‘The Party Of the Dead’: https://www.thevoiceofrussia.org/the-party-of-the-dead/.

-

Such as Vadim Zakharov and Antonina Baever:‘I, the artist Antonina Baever (Genda Fluid), no longer cooperate with any Russian institutions, including private galleries – all relations are broken.’ https://www.instagram.com/p/CbfNg8OsFHdGaFDalfVpjDMwgfMSb12zTPddMs0/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y= Zakharov also spoke out publicly during the 2022 Biennial of Venice, unrolling a poster before the Russian Pavillion where he had once exhibited, reading ‘I AM STANDING HERE IN FRONT OF THE RUSSIAN PAVILION AGAINST THE WAR AND AGAINST RUSSIAN GOVERNMENT CULTURAL TIES.’ See: ‘The War in Ukraine Has Seeped Into Venice’s Glamorous Art BiennaleThe War in Ukraine Has Seeped Into Venice’s Glamorous Art Biennale’ CIMAM [online], available at: https://cimam.org/news-archive/the-war-in-ukraine-has-seeped-into-venices-glamorous-art-biennale/.

-

‘Ekaterina Muromtseva Solo Exhibition: Women in black against the war’, available at: https://www.echigo-tsumari.jp/en/event/20220721_0822/.

-

Such as Anna Engelhardt orAnastasia Potemkina: ‘tickets and bar proceeds will be forwarded to Ukrainian resistance’, available at: https://twitter.com/engelhardt_x; ‘Donate to the Defenders of Ukraine’, available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CciJfMTPw63/?hl=en.

-

Evgeny Antufiev and Lyubov Nalogina, ‘Artist Statement: We are a long echo of each other’, available at: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://emalin.co.uk/media/pages/exhibitions/we-are-a-long-echo-of-each-other/a6f32d43fb-1665233941/emalin-evgeny-antufiev-and-lyubov-nalogina-artist-statement.pdf.

-

Evgeny Antufiev, [Instagram Post], 28 September 2022, available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CjEPb9OKib_/.

-

Evgeny Antufiev and Lyubov Nalogina, ‘We Are a Long Echo of Each Other’, 30 September–5 November 2022, Emalin, London.

-

The next topic of V-A_C in GES-2 was to be the notion of truth, truth both as a scientific or religious category (istina) and as an ethical concept (pravda). The following seasons were to deal with questions of gender and of colonialism, the notions of Mat, Rossiya and Kosmos Nash being points of entry to those, as at that moment announced both in the press map and on the website.

-

In 1920 Nikolay Trubetskoy published ‘Europe and Mankind’, part of his critical questioning of nationalism, that can also be considered one of the first decolonial books ever. In 1921 he launched Eurasianism, with intentions opposite to its present abuse, together with three authors of Ukrainian descent, with the book Exodus to the East. Forebodings and Events: An Affirmation of the Eurasians, (I. Vinkovetsky, Ch. Schlacks, Jr., Idyllwild (ed.), 1996). Even if the leap it wanted to make didn’t succeed to entirely liberate itself of the mindsets at that moment and if it was turned into an opposite dimension, it opened up a space of reflection for the future.

-

Hans Achterhuis, De utopie van de vrije markt, Rotterdam, Lemniscaat, 2010, p.16.

-

Anders Kreuger (ed.), The Welfare State, M HKA, Antwerp, 2015, available at: https://www.internationaleonline.org/library/.