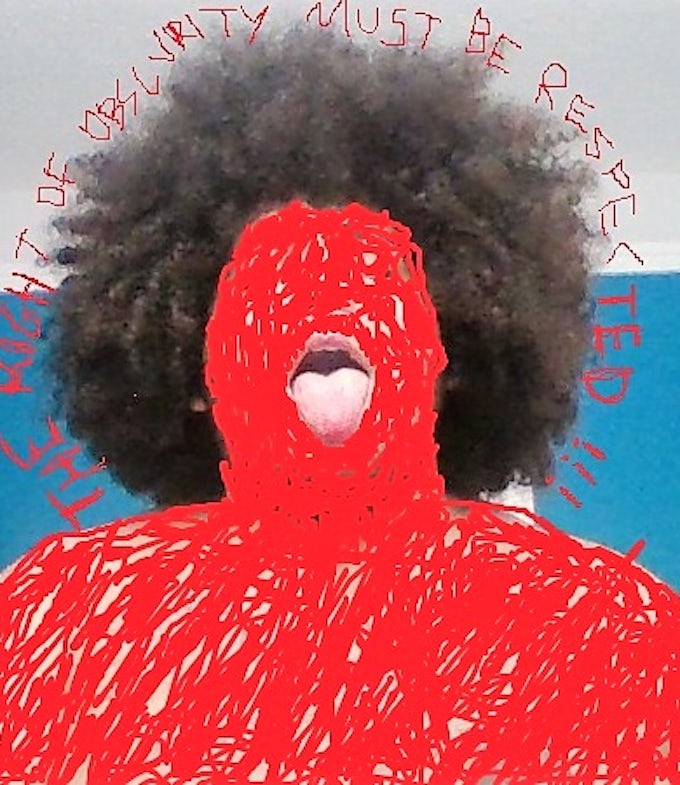

To Musa Michelle Mattiuzzi

Meus ancestrais todos foram vendidos

Deve ser por isso que meu som vende

— Baco Exu do Blues, ‘Imortais e fatais’01

Dana Franklin is the protagonist of the novel Kindred (1979), by African American science fiction writer Octavia Butler (1947–2006). The narrative weaves two complex temporal dimensions: the then-present of the 1970s, when in the US, as in other parts of the Western world, the civil rights struggles of populations systematically marginalised by democratic regimes gained more and more strength; and a past situated in the first half of the nineteenth century, a scenario in which the system of anti-Black slavery that shaped the world as we know it, was still in its fullest force.

Dana’s Black body is the bridge between these two historical dimensions. The leaps in time conditioning the character’s life throughout the plot are not mediated by any technical device (as in the classical narratives of H.G. Wells (1866–1946]). The time machine here is not metal paraphernalia, but the Black body itself, entangled in different temporalities linked by the socially conditioned repetition of a regime of unrestricted violence, which defines the relation between Black lives and the world that is revealed to us. Dana is dragged into the past and therefore reinscribed in the historical scene of enslavement, for this is precisely the scene that inscribed not only Black life but also the integrity of the Modern Text – and its temporal dynamics – in a continuous cycle of expropriation and destruction of Blackness as a condition for the emergence of social life and the mundane.

Although Butler presents Dana’s experience as speculative fiction, it does not seem pointless to me to ask the Black reader if, once confronted with the perspective of a Black body leaping into the past and thus having to reinhabit the political territory of a slave plantation, it is not possible to find a nexus between this narrative and our own life narratives. This question does not intend, however, that the plantation be thought of as a metaphor, but rather as a term that describes the system of appropriation of Black life as a matter deprived of value and, simultaneously, constitutive of what Denise Ferreira da Silva calls ‘ethical equation of value’. In other words, the Plantation describes a particular way of managing Black subjection in favour of the reproduction of a system of enslavement. This system of production makes processes of value extraction coexist with a regime of anti-Black violence.

In her essay ‘Unpayable Debt: Reading Scenes of Value against the Arrow of Time’, Ferreira da Silva provides a reading of scenes of value both in their economic and ethical dimensions. Starting from Kindred, the author studies the way in which Dana’s movement through time and space breaks apart from the sequentiality, separability and determination principles that guide Modern temporality. By doing so, Dana exposes the deep implications of the Plantation economy, in which race – as a regime of total expropriation of the body – and the colonial – as a regime of total expropriation of land as a resource – interact in the onto-epistemological, juridical and economic constitution of the capital-form as we know it.

Foregrounding both juridical (colonial) and symbolic (racial) violence, the analysis of racial subjugation begins with the acknowledgment that, for instance, emancipated slaves were not only dispossessed of the means of production, of the total value created by their and their ancestors’ labor, but that they were also comprehended by a political-symbolic arsenal that attributed their economic dispossession to an inherent moral and intellectual defect. From an economic point of view, it is thus possible to reconsider the postslavery trajectory of Black folks in the United States as one of an accumulation of processes of economic exclusion and juridical alienation – slavery, segregation, mass incarceration – that have left a disproportional percentage of them economically dispossessed. Negative accumulation, otherwise an oxymoron, perfectly describes this context. 02

‘Negative accumulation’ is the descriptive term articulated by Denise to highlight, in opposition to the Marxist reading of the colonial as a moment of primitive accumulation, the ways by which such processes reproduced race as a political and symbolical arsenal responsible for producing devices for the continuous and integrated subjugation of Black and racialised bodies, as well as land and colonised resources – foundations in the constitution of what we today experience as the capitalist production system. It is not a matter of thinking (as per Marx) from the captivity of sequentiality (i.e. of thinking of primitive accumulation as an element prior to value formation in the capitalist mindset) and separability (full expropriation of enslaved labor as a process formally detached from the analysis of labour exploitation in the context of capital formation), but rather it is a matter of paying attention to the simultaneous implications of the slavery and coloniality in the means by which value and times were defined in the formation of modern capitalism as we now know it, as the world’s production system.

Best-selling

Baco Exu do Blues’ lines in the epigraph to this text continues to haunt these reflections, because, ultimately, they also reflect my own position as an artist somewhat integrated in the systems of international contemporary art. The objectification and selling of the Black body at the core of Plantation slavery’s economy seems to be of such strength that it inscribes itself, in more or less brutal ways, in how, in the context of slavery’s lifespan, Black culture and symbolical forms of production are consumed and appropriated.

‘Meus ancestrais todos foram vendidos/ Deve ser por isso que meu som vende. (All my ancestors have been sold / That’s probably why my music sells.)’ That is probably why this text sells. Or why, according to some institutions, the boom in Black and anticolonial art and thought, that seems to define the courses of art and knowledge production on a global scale at the moment, is referred to as a trend, a market tendency. Since the commodification of this perspective – our perspectives – depend directly on a certain continuity between our artistic production and our social-historical place, maybe it makes sense to state that the selling of our music, texts, ideas and images reenacts, as a historical tendency, the regimes of acquisition of Black bodies that established the predicament of Blackness at the core of the world as we know it.

It is not a matter of – and I must insist on this – moralising our adhesion to these systems, for this is not simply a matter of agency. After all, Black experience, marked as it is by the dispossessive phenomenon of slavery and by the continuity of anti-Black violence in the period subsequent to the formal abolition of the plantation fields, necessarily questions apparently transparent notions of agency and consent. Coercive strategies have been updated, as we migrated from a system of total captivity to a fractal one where violence strikes us in other manners, thus building some internal asymmetry with regards to the Blackness diagram that allows, on a collective scale, our concurrent death and success.

The paradox of Black success is its reinscription into neoliberal capitalism’s systemic plan, not only formed by the total expropriation of Black labour value (central to the Plantation’s economic functioning) but also sustained by the arsenal of epistemic, juridical and ontological devices of raciality (Plantation slavery’s ethical basis). Frantz Fanon (1925–1961) notably states, at a certain point in Black Skin, White Masks (1952), that ‘negrophobia’ and ‘negrophilia’, although opposite phenomena on the spectrum of desire, are part of the same problem, namely the Negro as an a priori – a given. It is the racial, and not racism, that stands at the core of the Fanonian analytical framework, so the antidote for this modernity pathology (racism) cannot be summed up as the ‘valorization’ of Blackness, but needs also to include the intensive abolition of the racial as a difference descriptor, and of value as an organising principle of ethics.

Following the 2019 edition of Festa Literária Internacional de Paraty (Flip) (Paraty’s International Literary Party), there was a headline that echoed and repeated itself many times throughout Brazilian social media: ‘Out of the five best-selling authors, four are Black and one is indigenous’. The meaning attributed to this narrative was one attached to the country’s Representation Policies, coming up as a sign of the collective ‘empowerment’ of Black and indigenous peoples as framing contemporary systems of knowledge production. To me, such a headline has not failed to evoke, each time it reappears, the ghost of value as a device deeply implied in the arsenal of raciality. The conjunction of ‘best-selling’ with ‘Black and… indigenous’ works, therefore, as one of the spacetime curvatures in which Dana finds herself intermingled: I feel the world spinning around me and I am taken by a dizziness, my surroundings lose their shapes and I see myself being thrown into a spiral… The Black body is a time-machine. Every time we are best-selling, we come back to the same predicament. In another position.

Re-colonial scenes of difference valorization 03

In 2017, I went to Athens as a resident participant of a Brazilian project that had designed, in association with international art institutions and through The Parliament of Bodies, a platform for interaction between twelve artists as part of documenta 14. On the one hand, this program, known for facilitating initiatives for deconstructive formation and articulation of the sensitive, aimed to assert a certain distance from documenta and, thus, an implied endorsement of positions marginalised by the art system. On the other hand, documenta’s installation of super-apparatus in Athens was received with a great deal of wariness and tension by both the local art circuits and the international art system’s most judgmental sectors, due to its simultaneously paternalistic and extractivist character, supported by a very old power relation between Greece and German imperialism

In this sense, a whole ecology of terms, such as queer, blackness, decolonisation,deconstruction, feminism, anti-racism, dissidence, etc., was articulated by the project coordinators (both straight, white and cisgender male descendants of European settlers) alongside an appropriative approach to such terms and subjectivities, converted into trade currency in the framework of negotiations for project funding with different European art institutions (including documenta itself), which was certainly interested in all of these keywords and in the value assigned to them. Thus an entire speculative economy went on display as, once again, total values were extracted from the work of the dispossessed that were potentially – by the economy’s nature as speculative – infinite. This process of extraction created certain conditions of access (always partial and contested) for those of us who do not access the social world in a linear way, as it re-created the political territory of the plantation, reinscribing Black, indigenous, colonised, dissident lives (our lives) into ethical and economical value equations.

Such processes of ‘valorisation’ of subaltern lives, although linked to the emergence of supposed decolonial practices in the art system, seem to point, rather, in the direction of a re-centering of value as the mediator of our lives. What this has to do with the way in which decolonisation has been organised for the art system is not my focus now, but I have the impression that the problematisation of value, or, more precisely, of the re-colonial value extraction processes at the centre of the contemporary system of art, is an important part of the work that is necessary for the disarticulation of certain institutionalised ways of emptying and and undermining the power of the verb ‘to decolonize’.

In order to move further in the field of criticism, I want to think in contrast to one aspect of Suely Rolnik’s newest book, Esferas de la insurrección. Apuntes para descolonizar el inconsciente (The Spheres of Insurrection: Suggestions for Combating the Pimping of Life)(2019). I aim to search for the threads of implication between her approach to difference and the extraction, re-colonial metabolisation and interiorisation systems of politically subalternised differences in the political territory of value. It does not matter to me if Rolnik incorporated (or not) the term ‘colonial’ into the already well established concept of ‘capitalistic unconscious’ to appropriate the centre of a debate that is becoming unavoidable, for what is at stake here is what underlies the very core of all appropriation: the speculative procedure that extracts from our life forces – even before the formal movement of extraction – a value made of pure potential, stolen from us in an instant.

I will ground this critique in Rolnik’s broadly recognised reading of the work Caminhando(1963), by Ligia Clark. In the chapter ‘The colonial-capitalistic unconscious’, Rolnik focuses on presenting a model for understanding two trends in contemporary subjectivation politics and their implication in left-wing insurrectionary processes. The precise basis for Rolnik’s study is the Möbius strip, activated by Clark in her work, and the different cutting orientations that the artist proposes: Rolnik emphasises that, when the strip is cut several times in the same direction, it unfolds the same result infinitely. The theorist likens this phenomenon to a ‘reactive micropolitics’ (averse to all production-of-difference processes, this micropolitics constitutes the subjective program of fascism); reorienting the direction of the cut, however, always choosing a new direction (as long as the strip does not break) always produces a different effect. In other words: difference corresponds to effect. Rolnik then names this trend ‘active micropolitics’ and, with it, she populates her project of decolonisation of the unconscious – a project based on a principle of production and incorporation of difference that stands up to the reactive tendency to sustain, defend and evoke, at any cost, the domain of the sameness.

Aligned with a radical Black transfeminist methodology, I want to reexamine the conceptual narrative presented in the last paragraph; more precisely, I want to reexamine one of its formulations in parenthesis: the condition of production of difference as corresponding not only to the orientation of the cut, but also to the fact that the strip does not break. For, once the strip breaks, the game is over; and Clark and Rolnik’s bet seems indeedto be to play the game. The infinite potential of of this ‘active micropolitics’ in producing difference depends, therefore, on the fact that the strip always emerges as the inTrastruture of the game of difference. 04 Nonetheless, it is still useful to identify in these images an emblematic element that is often ignored, but that traces a strange continuity between the inFra and the inTrastructure of the clinical-political project underlined by Rolnik via Clark’s work: the white hand cutting and reassembling the Möbius strip when it breaks. If ‘the racial’ (the white hand) is the infrastructure that sustains the possibility of such an exercise – providing the material and subjective ground for the free election of an always different cut within the infinite – it is underwritten by the principle of ‘value’, which then forms the inTrastructure of this game. Ultimately, the program of active micropolitics, while refusing the regime of fascist subjectivity (which posits sameness as value), responds to the neoliberal program of cognitive capitalism (of difference as value), articulating a speculative operation whose effect is the infinite production of valuables. In Rolnik’s terms, difference presents itself as a transformation channel, stirring up a diagram of forces that precipitates the emergence of new and other ‘germs of the world’; coloniality – endorsed by racial capitalism (domain of the cognitive plantation) – functions mainly as a devourer of worlds and therefore feasts on difference. Nevertheless it does not cease to regenerate itself as a principle of social and political realism, domain of the common ‘Modern- colonial. This is how the valorisation of difference – that is, its inscription in the ethical, political and economic domain of the world as we know it – instead of opening routes for a possible decolonisation of colonised subjectivities and life forces, erects the very fences of the cognitive plantation.

The crossroads of Black life

What if, from this crossroads in which we find ourselves, our best chance of escaping the parameters of the cognitive plantation were to take place at the very moment when the strip of the ‘colonial infinite’ breaks? What if the difference we nourished, unlike that one modelled by Rolnik, had to be sown right then and there, in the breaking of the game of difference – an improbable geometry that exists in the blind spot of the equation of value?

Édouard Glissant (1928–2011), in the chapter ‘For Opacity’ of his book Poetics of Relation (1990), reminds us that ‘difference itself can still contrive to reduce things to the Transparent’, which is, in turn, one of the fundamental bases of the Western comprehension of understanding. He continues: ‘Agree not merely to the right of difference but, carrying this further, agree also to the right to opacity that is not enclosure within an impenetrable autarchy but subsistence within an irreducible singularity. Opacities can coexist and converge, weaving fabrics’. 05 The right to opacity is thus thought to be a condition of relationality, and not a break in the relation. As the affirmation of a relational poetics, opacity engenders an ethical generative territory of differences that manifest themselves outside the captivity of comprehension, beyond the boundaries of the intelligible, under the shadow of regimes of representation and registers of representability

This fugitive difference does not answer to the cognitive plantation’s choreographies, for it emerges precisely in the rupture of the game of difference; it is an interval in the re-colonial speculative movement that establishes, amidst the tremblings and stumbles of flight, an ‘ethics stripped of value’. If, in opacity, difference cannot be consumed or extracted, maybe we can create a conceptual and poetic fiction in which ‘opaque’ is one of the ways to say ‘quilombo’, and assume, thus, that the crossroads of Black life is located on a maze of tunnels that lead us from the cognitive plantation to the forest and from the forest to the fugitive settlement. Thus, instead of returning to the domain of value and recovering a position at the milestone of political colonial realism (becoming a being in the captivity of the world as we know it), this difference (that has as many names as it has shapes, and at the same time is nameless and shapeless) transposes the fences of the cognitive plantation and surrounds the system that had formerly enclosed it. As a fugitive lightning bolt, a mysterious rebellion, an abundance of Black life crossing the great night without turning on the light.

Footnotes

-

Denise Ferreira da Silva, ‘Unpayable Debt: Reading Scenes of Value against the Arrow of Time’ in Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (ed.). The Documenta 14 Reader, Munique: Prestel, 2017 p.107.

-

The notion of re-colonial is inspired by Francisco Godoy Vega’s thoughts in his book La exposición como recolonización. Exposiciones de arte latinoamericano en el Estado español (1989–2010), Cuacos de Yuste: Fundación Academia Europea e Iberoamericana de Yuste, 2018.

-

The notion of inTrastructure came into my arsenal of concepts at a study session conducted by Denise Ferreira da Silva during the third edition of The Global Condition (2019), an annual seminar co-organised by da Silva, Mark Harris, Valentina Desideri and Alyosha Goldstein at the Performing Arts Forum, France.

-

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, (trans, Besty Wing), Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990, p.190.

-

This formulation appears in the film 4 Waters – Deep Implicancy by Denise Ferreira da Silva and Arjuna Neuman, 2018.