During Soeharto’s New Order era (1965—98), the progressive term ‘alternative’, used as an idea or to describe art spaces, signalled an opposition to the authorities. 01 The reform period that followed, the reformasi, ushered in a time when ideas spun quickly, buzzing almost, and in which a number of alternative media and local civil initiatives developed. This increased activity reflected the intensity of local cultural production in Indonesia and was partly encouraged by the urgency to express the long- suppressed counterculture movement. Sensitive as these projects were to the social and political situation of the region, their lifespans varied, but the significance of what they produced proves that ‘alternative’ and ‘initiative’ are keywords by which to understand Indonesian society post-1998.

Ruangrupa is a Jakarta-based arts organisation established in 2000, when reformation ideas were still in the air. It functions as an outlet for studies of visual culture through exhibitions, the publication of a journal and writing workshops, and as such mirrors the shift of artistic practice from the production of objects to research. It was founded by a group of artists (Ronny Agustinus, Oky Arfie, Ade Darmawan, Hafiz, Lilia Nursita and Rithmi Widanarko), who met as students in different cities in the archipelago.

Youth and students played an important role in the demise of Soeharto’s New Order. During the reformasi, youth culture was given previously denied freedoms, and allowed to question things previously taken for granted. Writing about ruangrupa is writing about a youth movement.

At the same time, describing an artists’ collective is like remembering a long list of names — detailing those who came and worked for the collective, those who left and those who were replaced by others. It means telling the stories of a group of individuals, with different educations and paths, who develop their own attitudes towards work and eagerness to test their thoughts on arts and culture. Perhaps an artists’ collective resembles a sanggar, an Indonesian term for a collective space where members share their learning experiences under the auspices of a mentor. Ruangrupa is a contemporary sanggar, but without mentors.

Ruangrupa is divided into several parts: Art Lab; Support and Promote; Research and Development; and Video Art Division, which runs the well-known biennial OK Video festival. The organisa- tion is comprised of visual artists, video-makers, film-makers, performance artists, graphic designers, photographers, writers, researchers, music activists and architects.

In this conversation, Ade Darmawan, the group’s director, told me he was afraid he might confuse people with his answers. The conversation was conducted mainly through email and Yahoo! Messenger. Some of his emails came with attachments, essays he has written on alternative initiatives; others came with promises of further elaboration.

In compiling this text, I feel I am being forced to become a scavenger, collecting his thoughts from different sources — his writings, archives of Messenger conversations and files of his conversations with art critics and curators. I am wary of losing the trail of his thoughts, and afraid that I might lose some important aspect of our discussion in the translation process. I am worried that feelings that occurred during the conversation have been effaced by my translation. As I was translating his words and thoughts, I could not help thinking that English is more concise than Bahasa Indonesia. And are these questions enough? Shall I ask more?

This conversation is about the struggle of ideas in an arts organisation. My questions aim to capture insights into the relation between youth and the state, the state and society, artists in their environment; and about what might be gained from discussing the principles and work practices of an organisation that takes on these questions.

Artistic claims and statements are always changing. The ideas lodged in this interview should not be seen as fixed: as the artists’ collective grows older, new questions and doubts will emerge. The spread of the terms ‘state’ and ‘local people’ in the conversation inevitably makes the tone sound pompous, but this may serve as a reminder to stay alert to and question the fate of reformasi, which marked the beginning of the story of contemporary alternative spaces in Indonesia. Will the doors to freedom stay open? What have local initiatives done to keep them so? — Nuraini Juliastuti

The Relation Between Artists and the People

Nuraini Juliastuti: The story of my relations with ruangrupa (often called Ruru) began with Karbon, the quarterly art journal it began in 2002. 02 There are two striking things about Karbon: firstly, the logo of ‘RAIN Artists’ Initiative Network’ that appears on its cover, signalling its connection to a global art network. Secondly, its longevity. Ruru may not be the first organisation to publish a visual art journal, but it is one that has lasted. Could you speak a little about Karbon?

Ade Darmawan: Karbon works to fill in the gaps in the publication of visual art reviews and cultural analysis, and functions as an intermediary medium between cultural writers and art critics. Each edition was initially designed to reflect our organisation’s programmes, and to provide space for our research findings, but Karbon has developed to be a separate research division in the process. As regards RAIN, its members are artists’ initiatives from Southern countries such as Mexico, Argentina, South Africa, Brazil, Mali and India. We see RAIN as an important network to build on apart from the local and Southeast Asian network we participate in.

NJ: This is a classic question: what is the role of an artist in today’s Indonesia? Do you think that art should have a significant impact on the local level? Can an artist walk and move without ‘feeling guilty’ or ‘feeling the need to give a hand to the people’, as popular expressions have it?

AD: [Laughing.] I think it has to do with how we see our works. An artist, for me, must be able to constantly shake the faith of the people and everything that surrounds him or her, and contribute critically to social negotiations over existing values. Artists, local people, corporations, religious institutions, art and cultural institutions go head-to-head everyday. An artist is no longer positioned as the saviour of the world. It sounds so 1980s! It is too heroic.

NJ: But by publishing a journal, you are undeniably heroic. Even if the word ‘heroic’ sounds exaggerated, Ruru attempts to improve art infrastructure at the local level. In an interview with the art critic Hendro Wiyanto, you said that the shift in artists’ working patterns from production to research is the only possible way of augmenting visual art’s critical power. 03

Meanwhile, the scholar Melani Budianta defines post-1998 cultural activities as part of ‘an emergency activism’. 04 They are a response to an emergency situation; activities conducted to fill in holes in our environment and to oppose the state. Connecting your explanation of Karbon to Budianta’s remark, Karbon is indeed an emergency activity. It is also part of the knowledge production of alternative spaces.

AD: We are witnessing artists’ active roles in the development of the local contemporary art infrastructure, and indeed we see our works as alternative initiatives. The state has long been absent from our art and cultural landscape. Various forms of support for the production of visual art — such as vigorous art critics, strong educational institutions and art publications, spaces for art discourse and art appreciation — are at a minimum. If the system of visual art production is a chain, we have a broken one. Some artists’ initiatives and cultural organisations have been trying to mend this chain and to elevate the scope of their work to a higher level. But I do not see their work as a direct opposition to or an antithesis of the state. Rather, it is a response to an ever-changing society. The organisations develop relevant visual art practices to local social problems. They work as fixers. Importantly, such visual art practices are independent from the state’s art infrastructure. They do not connect to, for example, local arts councils in provincial capitals. In Indonesia, there is no partner- ship among independent arts organisations nor state institutions based on mutual benefit, and this reflects the failure of the state-designed art infrastructure to deal with the rapid development of ideas on the local level. I prefer to look at the works of initiative spaces as ‘contextual responses’. Performing a series of experiments in their local environments, they develop an applicable model to respond to local needs. Such contextual responses, occurring in different places and sometimes short-lived, develop into local survival strategies. In the absence of formal art infrastructure, they work to improve the local system. They attempt an ideal system, even if that is only an illusion.

Alternative

NJ: Rather than protesting anything commercial and mainstream, in the conversation with curator Haema Sivanesan for the Gang Festival in Sydney in 2006, you stressed the importance of developing a strategic and long term plan for an art infrastructure that differs from the Western model.5 Your use of the term ‘fixer’ to refer to work practices of alternative spaces is also interesting; it overlays such practices with an underhanded or illicit character — or with an alternative character, to be precise. We are now entering a period where the concepts on which an alternative space bases itself need redefinition: ‘the local’, ‘the empowerment of society’, ‘development’, ‘public participation’, ‘communities’ and even ‘people’ all need reviewing. In regard to this matter, I remember you talked about ‘the bottle cap philosophy’ — of how to open a bottle without a bottle opener, but with a nail instead, during our discussion at the ‘Cultural Performance in Post-New Order Indonesia: New Structures, Scenes, Meanings’ symposium in Yogyakarta in 2009. How would you explain the trajectory of the meaning of ‘alternative’?

AD: We are in the middle of failed modernism, illusive nationalism and national identity, and the products of corrupted power. Instead of keeping clear orientations, they lead to disorientations. We are left with only one position, to become greedy consumers. What I am trying to say is that through our works we are developing an alternative system. As the consumers of the products of social and cultural history, we are capable of developing an attitude that is a mixture of collaging, mix-and- match activities and destruction and reconstruction of practices so as to accord with local needs. What is dysfunctional is functional. The dysfunctional bus stop story is a good case in point. There are so many dysfunctional bus stops around us. I do not think our public transportation system acknowledges the bus stop concept, as in Indonesia one can get on and off a bus anywhere. Bus stops often transform into a kind of convenience store where organic alliances take place. In the afternoon we see bonds between a newspaper seller and a cigarette seller, and during the night the bus stop changes into a food stall.

Such talent for developing new attitudes is the capital for an experiment in exploring social designs in a wider context. It is the self-organised design where new negotiations are taking place. The nail that serves as a bottle opener is a metaphor for strategies designed by alternative initiatives. The Yogyakarta-based Cemeti Art House conducted its activities in a rented house — like many post-1998 initiatives do — which was converted into a contemporary visual art gallery in 1988. I began to see these alternative initiatives as medium-scale public institutions. A rented house is the headquarters, which also serves as a studio, a gathering and exhibition space and a music venue. It is a situation where the artists-cum-activists of an alternative space — the valid representation of the people — envisage their positions among the people. As such, it imbues the space with local values. An artist shares a position with the local community, and local communities participate in the initiative’s activities: local festivities, workshops for kampongyouth, an Independence Day celebration, a public cinema, etc. The debate over whether or not something is considered ‘art’ eventually disappears.

Jakarta

NJ: What kind of an environment does Ruru need to make its work? I understand your personal closeness to Jakarta and how you see it not only as a living space, but also as an ideal working space. I initially thought it was just a romantic choice. But from what I have seen of Ruru’s works, as well as some of your works, I have begun to understand that Jakarta is, as you say, ‘a necessary condition for the organization to exist’.05 It may offer the disorderliness that we need.

AD: The emergence of local artists’ initiatives often responds to the specific needs of particular infrastructure. Artistic strategies are designed in accord with the ecosystem in which an artists’ initiative lives. In Ruru’s early years, we wrote a series of critical essays on Jakarta. It is a city that has lost its social functions in favour of commercial activities and therefore one whose inhabitants have the potential to develop creative capacities. The relation between visual art systems and the city’s infrastructure is an important context of our works. Since 2004 we have organised the biennial Jakarta 32°C. It is an event for university students in Jakarta that consists of workshops, presentations, discussions, film screenings and art exhibitions. The early stages of Ruru’s development took place while we were still students, and students have always been important participants in our activities. If we always say that the local infrastructure for art education is lacking, we have to try to develop an alternative method. This biennial is one of our attempts at developing such a method. During the event, a series of meetings takes place to map what forms of creative and critical spaces are needed, and how the youths view the city space. A student network and spaces for public discussion are organised. We hold public workshops to invite students to examine the details of city spaces, aspects of visual culture, city designs, local city regulations, local practices and local economic infrastructure. Students are challenged to offer their statements, interact with a wider public and speculate on alternative visions. Local people’s changing views of the city are an important factor. The scope of our battles is no longer limited to the vertical area — of state and society — where we face the authorities. We have been battling against corporations, our own neighbours and those who have different perspectives on how certain ideologies and beliefs should be articulated. As the battle zone has been narrowed to horizontal relations, a city becomes more important than the state. Our artistic approach — and the artistic role we take — will only grow well relevant to the messy, sweaty and untidy space of Jakarta.

Key Artistic Practice

NJ: What is the key artistic practice for Ruru? That may sound a little bit formulaic, but in the case of Ruru, at this particular historical juncture, it may be an important question to ask. It is also a reflective one: a reflection of the original impetus for the organisation, and a series of tensions that revolve around its artistic production.

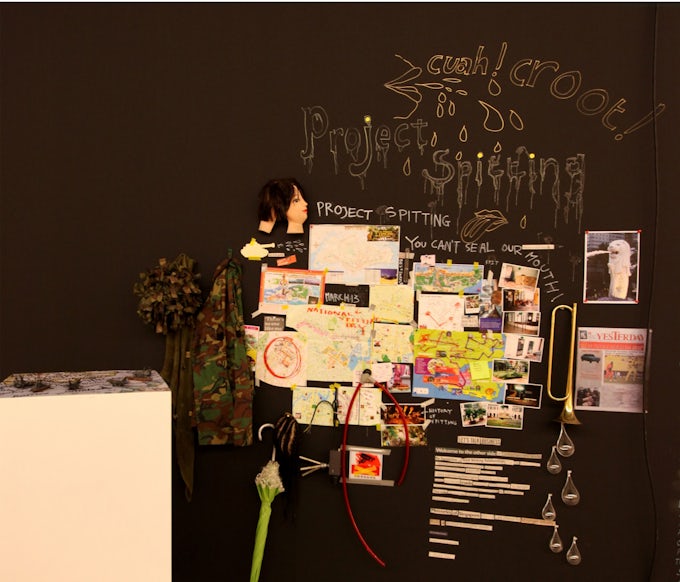

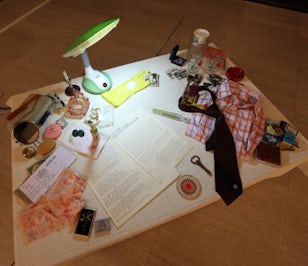

AD: Since its inception, Ruru has held that the research process constitutes a great proportion of its artistic production. It is a critique of and an attempt to transform the artistic tradition at the local level. Taking this further, we hope to not only develop it into a critical cross-disciplinary practice, but also a social practice. Our works focus on project-based artistic works, articulated in collaborations with other artists and artists-in-residence projects. Our method of presenting works also allows the audience to read and examine the archives of our research and production processes. Seeing an artwork is not the only way of appreciating and approaching the idea behind it. If we see an artwork as finished, through such a presentation we hope to expand and complicate its ideas.

Network

NJ: ‘Network’ is one key concept in discussing cultural productions in post- 1998 Indonesia. In 2010, you organised two exhibitions of alternative spaces and visual art communities, ‘Fixer’ and ‘Ruru&Friends’ at North Art Space and National Gallery in Jakarta, respectively. Both exhibitions underlined ‘network’ and ‘alternative’ not only as two essential concepts in analysing art and cultural practices at a local level, but also as the crucial value to staying alternative and participating in a particular network. Here I want to explore the meaning of ‘network’. Why do you think it is constantly being contested, and what aspects serve as a basis for Ruru’s network development?

AD: We are already connected. What matters is what is communicated and exchanged within these connections. The word ‘network’ often translates into an infrastructure development that ultimately does not engineer ways for people to have discussions with one another. It is like providing a table and chairs for a meeting. In the digital era, the concept of the ‘network’ needs redefinition. In a network situation where there is no need for communication, nothing will happen. There will be no new ideas created.

In the case of Ruru, a network is a precondition for our work; it is like the idea of building a friendship. It is organic, spontaneous and open. Often, building a network also means a political act. Over the last ten years, we have witnessed the rise of independent art groups in Java, from big cities like Jakarta, Bandung,Yogyakarta,Surabaya,Semarang and Cirebon to Jatiwangi in West Java. They emerged as new vibrant cultural centres where large-scale activities, such as international biennials and festivals, are taking place with a DIY spirit that connects these events to local and state infrastructure. The creation of national and international networks among art projects with critical ideas, social impact and new artistic approaches is an interesting phenomenon, which works to redefine and correct the relation between centre and periphery. Artists and cultural activists are now the negotiating partners of the government, and are allowed to participate in the decision-making process, in spaces that would otherwise be impossible to access. However, what is lacking at the local level is an alternative network that serves as a platform for organisations, which share the same vision to strengthen the bargaining positions within wider social, cultural and political contexts.

Art of the Present

NJ: Here I want to explore the relation between Ruru and the ‘youth’, which is a problematic category. It may refer to the output of the organisation, which talks about a history of the present. OK Video festival, in particular, suggests a form of support for video art development of the moment and indicates a need for examining the politics of visual culture at a local level. But ‘youth’ may also refer to the founders of the organisations, who are still considered young. Why do you think we all choose to talk about the ‘history of the present’?

AD: It is true. We talk about today’s realities. It makes people identify us with ‘newness’ and ‘youngness’. There is always a strong sense of cynicism towards ‘old people’ in our generation. Contemporary things are more relevant to our life, but history is important nonetheless. It needs to be continuously discussed, reread and connected to the present.

Religious Readings

NJ: What books or other reading materials inspire Ruru?

AD: We are part of the 1990s generation, which greatly admires that of the 60s. The span of our reading materials is wide, but we share similar interests. We read history, philosophy and cultural textbooks, postcolonial writings, leftist radical books — anything really. Maybe we are just a bunch of nerds. As visual art and design students, we admired Art Spiegelman’s Rawcomic books, Juxtapoz and Ray Gun magazines and David Carson’s works. The founders of Ruru share similar social and economic backgrounds. We come from the families who chose to not to be rich during New Order. I suppose our critical thoughts are partly informed by that.

NJ: Can you explain the knowledge- transfer process operating within the organisation? How do certain views of Ruru activists circulate within the organisation, to be used as the basis for works?

AD: Ruru is like a beehive or an ant colony, where each person piles up his or her own knowledge, and lets the others take from it. Informal discussions take place spontaneously and new ideas emerge from exchange practices. Rather than a knowledge-transfer process, what we see is a knowledge transaction. Ruru works like a football team. Each person works and plays hard by his and her own strength on a horizontal field. We have visual artist-cum-band manager Indra Kusuma, performance artist Reza Afisina, writer Mirwan Andan and architect-cum-writer Ardi Yunanto, among others. We believe that our idea supply is abundant, and therefore consider ownership issues to be minor. Ideas will be shared and combined with others’ ideas. It has to do with our commitment to collaborative practices as an important working method. It has informed the way we view the ownership of an idea and knowledge transaction.

Footnotes

-

Editors’ note: Soeharto’s New Order emphasised national unity, including a policy of transmigration that bred substantial local discontent and hence ethnic division as well as economic inequality across the Indonesian archipelago. Soeharto also prioritised economic development under the guidance of a team of Western-trained economists, and the military enjoyed a powerful influence in politics. Following the Asian financial crisis in 1997, poor economic performance, disaffection within various elements of society and burgeoning criticism of the regime culminated in the protests, violence and eventually riots in May 1998 that led to Soeharto’s resignation and the end of New Order, after 32 years. The reformasi (reform) period that started in 1998 was initially turbulent, but it soon led to greater political stability and an improved economic situation.

-

Since 2007 it has appeared as an online journal. See http://www.karbonjournal.org/ (last accessed on 16 April 2012).

-

Ade Darmawan and Hendro Wiyanto, ‘Ruangrupa: Ruang Alternatif dan Telaah Kebudayaan’, Kompas, 30 January 2005.

-

Melani Budianta, ‘The Blessed Tragedy: The Making of Women’s Activism During the Reformasi Years’, in Ariel Heryanto and Sumit K. Mandal (ed.), Challenging Authoritarianism in Southeast Asia: Comparing Indonesia and Malaysia, London and New York: Routledge, 2003.

-

Email to the author, 23 March 2012.