Reshaping the Field: Arts of the African Diasporas on Display is the first publication to focus exclusively on African diasporic art in the US and UK through the histories of Black art exhibitions. 01 Combining perspectives from art historians, theorists, artists and curators – including a number of historical protagonists and contemporary witnesses – we had the opportunity to gather knowledge that traverses art historical research and oral histories while generating primary resources. Reshaping the Field aims to reflect on the sociopolitical circumstances essential to the emergence of a field of study and mode of exhibition that constantly reshapes itself and challenges normative orders.

The idea for this book, and the conference that preceded it, emerged out of my teaching practice at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College (CCS Bard), which has a strong focus on exhibition histories. More than a decade after the publication of Bridget Cooks’s Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum (2011), a seminal publication in directly addressing historic exhibitions focusing on African diasporic (or more precisely, African American) art, it is still necessary to consider the record of exhibitions that have told the story of Black art and its networks. Furthermore, it is urgent that we create fresh resources for art historians, curators, artists and researchers in the fields of exhibition studies, museum studies, cultural studies and beyond, in order to spark new research that will highlight emerging histories not necessarily considered in relation to modern art history.

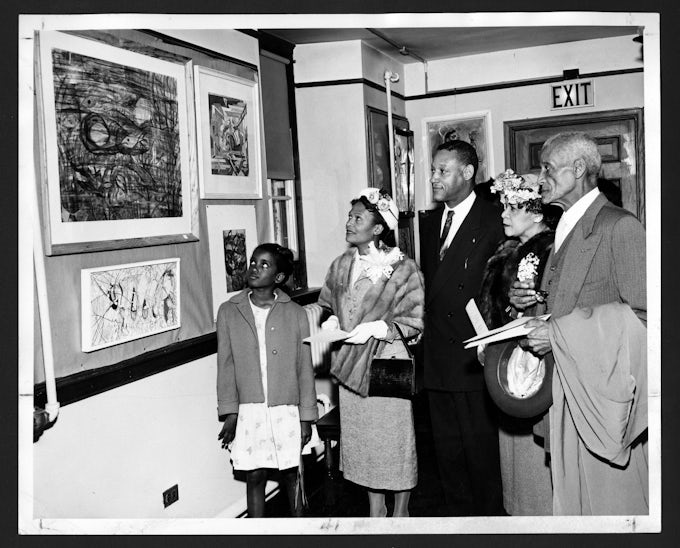

Reshaping the Field stresses the profound role of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) – and their artist networks – which articulates itself in the book’s first section, ‘Marginalized Legacies and Networks’. HBCUs exhibited Black artists and collected their work during times when the quality of the work was often undermined; these institutions fostered a dialogue that spanned across the United States and to the African continent. The contributions by Richard Powell, Abby Eron, Cheryl Finley and Jamaal B. Sheats map the rich networks that established the foundations for the flourishing of Black art, art education and artists, and its ongoing importance to exhibitionmaking today. Although HBCUs were foundational for African American art, the essays in this anthology prioritize thinking about the dialogical nature of the Black diaspora, considering Blackness in its multiplicity instead of binding it to nationality.

When I emphasize multiplicity in this introduction, I also wish to ask: What do Black audiences want and need to see in an exhibition to feel connected and affirmed? This question challenges the ways we think through Blackness in exhibitions in different contexts – New York, Los Angeles, London, Chicago Berlin, Paris, Stockholm, Salvador de Bahia, Port-au-Prince, Nassau, Accra, Cape Town or New Orleans. As a person who has lived, studied and worked on different continents – Africa, Europe and, now, North America – and in a range of countries – Ghana, Germany, Netherlands, the UK and the US – I am particularly sensitive to the ways in which the Black diaspora is informed by diverse perspectives and context-specific experiences. I argue that it has never been possible to connect artists only through a racial signifier, andI advocate that we be attuned to the distinctiveness of practices, formal expressions and cultural frameworks. And yet, nothing is more exciting than looking at the contemporary spectrum from various historical perspectives in order to identify commonalities despite differences in form and subject positions, which are often shaped through relationality.

Reshaping the Field builds on a long history of scholarship addressing the diversity of practices and aesthetic impact that African diasporic artists have had on global cultures, as manifested in book publications such as Alain Locke’s The Negro in Art (1940), James A. Porter’s Modern Negro Art (1943), Cedric Dover’s American Negro Art (1960), Judith Wragg Chase’s Afro American Art and Craft (1971), Samella Lewis’s African American Art and Artists (1972), Harry Henderson and Romare Bearden’s A History of African-American Artists: From 1972 to the Present (1993), Deborah Willis’s Picturing Us: African American Identity in Photography (1994), Richard Powell’s Black Art and Culture in the 20th Century (1997) and Sharon F. Patton’s African-American Art (1998); for the British context, I want to also mention Kobena Mercer’s Welcome to the Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies (1994), David A. Bailey, Ian Beacom and Sonia Boyce’s Shades of Black: Assembling Black Arts in 1980s Britain (2005) and Eddie Chambers’s Black Artists in British Art: A History Since the 1950s (2014).

Building on this exciting scholarship allows exhibition histories to expand the ways in which we consider art and its publics. This is seen in the way that contributors to ‘Marginalized Legacies and Networks’ articulate the connections between different HBCUs, the African continent and wider Black diasporas. It is further developed in the section on ‘Dialogics of Diaspora’, which engages with Black British art and the relational nature of Black artistic and curatorial practices. One articulation of such expansive practice is Mora J. Beauchamp-Byrd’s reflection on ‘Transforming the Crown’, which she curated in 1997; the essay gives insight into how the exhibition came into being and how we might consider it today. Marlene Smith, in conversation with Claudette Johnson, uses the 1982 exhibition ‘The Pan-Afrikan Connection: An Exhibition by Young Black Artists’ as a starting point for an exploration of the energetic Black British arts scene of the 1980s that fostered Smith’s practice. And Lucy Steeds engages with two of the collectives that emerged from this milieu, Black Audio Film Collective and Sankofa Film/Video Collective, following their works’ presentation across cinema, television and exhibition contexts to evoke multiple resonances and publics.

In the section ‘Between Inclusion and Making Space’, Brittany Webb contributes a succinct revisitation of Bridget Cooks’s Exhibiting Blackness and its argument that Black artworks (and artists) are often caught between anthropologically organized exhibitions versus exhibitions aimed at establishing a universal art. For Webb, the pages of Exhibiting Blackness offer a history of the present. Webb highlights the protests activated in New York by the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 1969 exhibition ‘Harlem on My Mind’, and she identifies the reflection of this critique in recent activism against institutional exhibition practices, and how the perception of such critique often remains ahistorical. Howard Singerman’s contribution stresses how Black artists have insisted on inclusion by organizing exhibitions and institutions outside of mainstream museums by strategically creating Black spaces, with particular reference to the historical examples of Cinque Gallery and Acts of Art in New York City. 02 Julie McGee shows how Black artists including David C. Driskell strategically utilized the museum to highlight their achievements in major projects such as ‘Two Centuries of Black American Art’ (1976). Driskell, in particular, transformed the field by drawing upon his rootedness in artistic, educational and curatorial practice; his professional and personal networks; and the institutional network of HBCUs. 03

Such a transformation becomes especially apparent in the section titled ‘Ruptures’, with particular reference to ‘Freestyle’ at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2001. Senam Okudzeto, one of the participating artists in ‘Freestyle’, provides a reflection on the experience of that project in light of the current state of the art field and new problematics that have emerged for Black practitioners: ‘Is the same market that sold the ancestors in fact actively commodifying white guilt? Is there a process at hand, which is in fact colonizing the discourse of decolonization?’ In my contribution, I situate ‘Freestyle’ and explore the complex tensions and possibilities that it introduced via the concept of post-black and how it ruptured the arts. Derek Conrad Murray extends these questions through a deep theoretical engagement with the question of Black representation.

These chapters show the necessity of Black group exhibitions and their networks, which have secured, collected, archived and preserved cultural histories for present generations. They are explored here with the hope that they may influence and serve as case studies for exhibitions to come. Students of colour at CCS Bard, where I work, are often confronted with the question of identity signifiers for curatorial frameworks. As the present volume reflects, this is not a new problem. While students often want to work with artists in creating group shows based on artists’ shared identity categories, they are reluctant to use these markers for fear of marginalization; or the critique of oversimplification of artistic practice; or the feeling of being pigeonholed as ‘curators of colour’. However, the history and necessity of exhibitions that use a racial signifier has been contested since its beginning. In 1946, Romare Bearden stated: ‘The work of Negro artists reflects all the artistic trends of the time.’ 04Bearden emphasized Black art as a part of the American narrative – and yet the quality of Black art is consistently questioned and excluded from the dominant narrative of art history and exhibition-making. In 1968, painter and art educator Charles Alston equally emphasized the bias by art critics reviewing Black shows in an oral history interview. 05 This legacy of bias can be traced back to one of the first Black group exhibitions in an art museum in the US, which was supposed to give African American artists a larger platform and visibility: ‘The Negro in Art Week: Exhibition of Primitive African Sculpture, Modern Paintings, Sculpture, Drawings, Applied Art, and Books’, organized by the Chicago Woman’s Club in consultation with Alain Locke at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1927. The museum’s director, Robert B. Harshe, noted to the white curators that the exhibition should ‘conform as near as possible to standards set by regular art museum exhibitions and exhibition galleries’. 06 Here, ‘regular’ in this sentence may be interchanged with ‘white’, which highlights that whiteness, however lucid, was used as a measurement of quality as well as of the constraints under which Black artists and curators had to exhibit.

When we look at the history of Black exhibitions, we look at more than just the intricacies of artistic display and inclusion or exclusion. The reason why Black art exhibitions in particular are a tremendously rich resource to understand artistic movements, political shifts and aesthetic developments is that Black exhibitions tell cultural histories and allow for revelatory debates to emerge about our current moment and potentially moments to come. This notion of futurity has a special focus in this book’s section ‘Curating Black Futures’, which foregrounds the voices of contemporary Black curators and practitioners as they articulate their visions, experiences and hopes for the field. As part of this dialogue, which features contributions by Amber Esseiva, Languid Hands, Brittany Webb and Serubiri Moses, the shared yet often isolating experience of being Black in predominantly white institutions is problematized, especially as a historical through line.

Institutions are reminded by social justice movements such as Black Lives Matter that they are intrinsically founded in White Supremacy – that gratuitous violence against Black people is not necessarily new. Bridget Cooks’s opening essay in this anthology highlights the profound anxiety that Blackness provokes and how understanding this anxiety can help us in rethinking art history, museums and institutional practice. As Richard Powell expressed so eloquently in a recent interview, BLM’s demands are a reverberation of other moments in time where people have stood up and said, ‘enough is enough’. Black Lives Matter is in some ways a twenty-first-century reverberation of ‘Black Is Beautiful’ and ‘Black Power’, and ‘Black Power’ was a reverberation that hearkened back to the 1920s and 30s, to the Jazz Age and the Harlem Renaissance. So, we’ve always had these periods in Black America, intermittently, where a particularly vocal and expressive movement says, ‘I matter, I exist.’ 07

Black artists’ works are now achieving record sales at international auctions as collectors are focusing on expanding their collections with pieces by artists of African descent. 08 Educational and art institutions are forced, again, to reflect on their legacies and to make significant structural changes. With each reverberation of the existence and mattering of Black Life comes a wave of exhibitions focusing on Black art.

I hope this publication will serve as a resource for how we can make connections to the past, and how we can gather materials and knowledge to support and enable artists, curators, critics and art historians in making well-informed and nuanced curatorial decisions and writing art histories that tell stories of multiplicities beyond historical bias.

Footnotes

-

Editors’ Note: Across this publication there are various approaches to the capitalisation of ‘Black’/‘black’; rather than apply a universal rule, in each essay we have followed the usage of individual authors.

-

This debate continues to be important today, in projects such as Titus Kaphar’s NXTHVN in New Haven; Yinka Shonibare’s Guest Projects in London; and Noah Davis’s Underground Museum in Los Angeles, to name just a few. See also the contribution of Languid Hands to this volume.

-

This debate continues to be important today, in projects such as Titus Kaphar’s NXTHVN in New Haven; Yinka Shonibare’s Guest Projects in London; and Noah Davis’s Underground Museum in Los Angeles, to name just a few. See also the contribution of Languid Hands to this volume.

-

Nicholas Miller, ‘The History of the Group Exhibition from the Harmon Foundation to Black Male’, in Eddie Chambers (ed.), The Routledge Companion to African American Art History, New York: Routledge, p.301.

-

See Bridget R. Cooks, Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011, p.43.

-

N. Miller, ‘The History of the Group Exhibition from the Harmon Foundation to Black Male’, op. cit., p.303. Emphasis mine.

-

Folasade Ologundudu, ‘Decades Ago, Richard J. Powell Was Once Among Only a Handful of Scholars Dedicated to Black Art History. Here’s How He Has Seen the Field Change’, Artnet, 18 February 2021, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/richard-j-powell-interview-1944754.

-

Nate Freeman, ‘Black Artists Shatter Multiple Records in $392.3 Million Sotheby’s Sale’, Artsy, 17 May 2018, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-black-artists-shatter-multiple-records-3923-million-sothebys-sale. During my time at CCS Bard the collection has grown exponentially with regard to Black artists.