Tense beats echo, and a curtain opens on the entry scene. Soon, as electronic sounds spread out, immensely magnified, a human body becomes visible, divided by oblique lines and light, completely filling the three walls where four performers appear in a specific order. The main part of artist siren eun young jung’s audio-visual installation A Performing by Flash, Afterimage, Velocity, and Noise (2019) – which represented the Korean pavilion at the Venice Biennale – is a tight black box-like space of 5 × 5 × 4m, charged with beats in which light circulates like laser beams across the three walls that form a U-shape in the square projection room. In this work, overflowing and overwhelming with sound and image, performers reconceive the strange and uncomfortable human body as a language for the stage.

Among the four performers whose images are projected on the three walls, lesbian actor Yii Lee (이리), known for her unique, transgressive, characters in a male-centred theatre world, soliloquises about her floating position and the lack of understanding from family and society. Drag king Azangman, who has been struggling to expand the South Korean drag community, represent the self-renewal of a person who breaks through oppression via explosive primal release within their body. Seo Ji Won (서지원), a person with severe disabilities who is Director and a member of the Disabled Women’s Theater Group ‘Dancing Waist’, creates exceptional performance aesthetics in which she alternates between restricted possibilities for action in a wheelchair and the singular movements such limitations make possible. Finally, electronic musician KIRARA’s musical activism translates the bodily dissonance and segmentation of transgender experience and reflects on their body in transcending the constraints of reality.

Based on their physical experiences, these performers bring bodily singularity to the stage. From their position as ‘Others’ in contemporary South Korean society, these acts escape genre stereotypes through formal challenges in performance. Moreover, the ‘anomaly’ they perform on stage is of importance to gender politics at large. At the Venice Biennale, their soliloquies, sounds and gestures move between constraint and liberation; in return, the sensations induced by the beats and powerful sounds in the work as a whole overwhelm the audience’s visual experiences and bodies. Unaware, viewers start to dance and become one with the performers in the throbbing room.

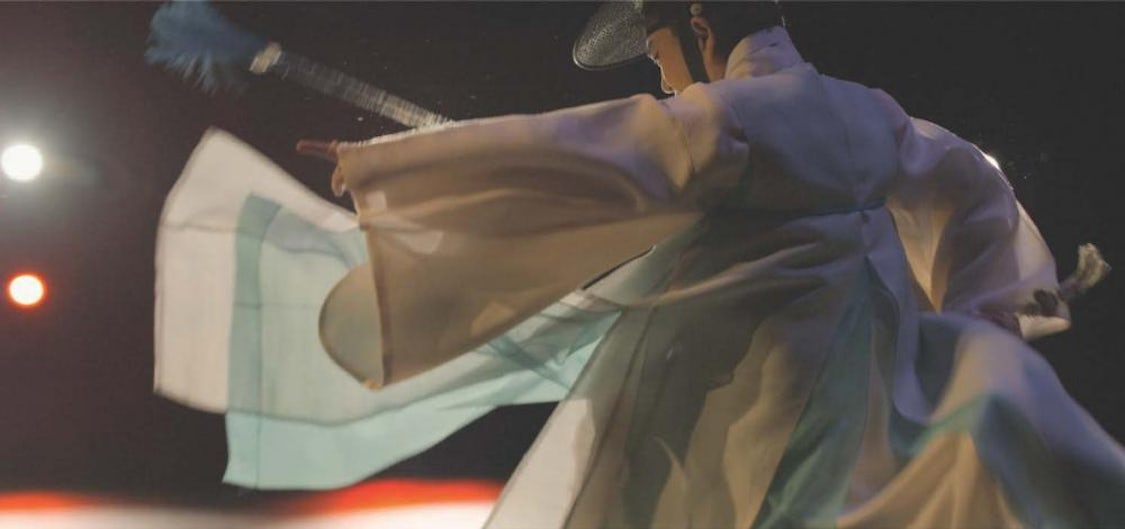

Installed at the entry to the Korean Pavilion, the three monitors that make up the first part of Performing by Flash, Afterimage, Velocity, and Noise’s, show yeoseong gukgeuk [여성국극, Korean or National women’s theatre] actor Deung Woo Lee dancing solo, performing pansori [a traditional form of solo vocal performance] and putting on make-up in a large theatre. The actress’s traditional Korean men’s costume, shown across the monitors, and the immersive experience provided by the electronic music are somewhat heterogeneous, seeming not only unrelated but almost diametrically oppposed. What bridges them within this context is ‘queer performance’. Here, the artist summons and reaffirms yeoseong gukgeuk as a forerunner of queer performances. On view is a contemporary aesthetics of anomalousness, which establishes yeoseong gukgeuk as the imaginary origin of a modern and historical queer genealogy. In this work as well as in her latest – including Anomalous Fantasy (2016–ongoing) – siren eun young jung articulates genderqueer ‘anomaly’ in the form of uneven, unconventional and anomalous acts and movements.01 Celebrated by the artist for their aesthetic singularity, the aesthetics and politics of contemporary queer performances are taken from the restricted sphere of the LGBTQI+ community to the stage of ‘official’ or ‘established’, performing arts.

A university student in the 1990s, siren eun young jung belongs to a generation who grew up under the influence of campus feminism in South Korea. Since her earliest works, she has attempted to expand feminist language in contemporary art. Through narratives reminiscent of video essays, her early pieces addressed issues including the social violence and oppression inflicted on female Others and their vulnerability as they were ceaselessly pushed out of society. Having brought about some change, feminism in South Korea lost its driving force and dwindled in the 2000s. It nevertheless continued to be a personal concern for the artist, serving as an important ressource and impetus for her work. Encountering aged yeoseong gukgeuk actors by chance and beginning to exchange with them around 2008, she initated the substantial Yeoseong Gukgeuk Project (여성국극 프로젝트, 2008–ongoing) based on a decade of ethnographic research that approached tradition from the perspective of subversive gender performativity.

A form of musical dance theatre begun in the latter half of the 1940s, yeoseong gukgeuk enjoyed great popularity in the 1950s after the Korean War (1950–53). Formally, it is viewed as an offshoot of changgeuk (창극), the theatrical staging of a traditional Korean solo vocal performance genre called pansori (판소리).02 However, just as it means ‘Korean/national women’s theatre’, in yeoseong gukgeuk female actors play all of the roles. It can thus be seen as an opposite version of traditional Chinese opera, which consists of all male actors. A Flower in Jail, staged in 1948 by the Women’s Gugak (국악,Traditional Korean Music) Association, initiated yeoseong gukgeuk. It came out of the women’s determination to create their own stage, their antipathy towards the authoritarianism and violence of male artists, and their will to fight back against the prolonged sexual and monetary exploitation of female students by male masters in their training – an apprentice system of oral transmission that predominates in traditional Korean music circles.03 In spite of a hostile environment, women’s awareness expanded during the modernisation process. Although the very first yeoseong gukgeuk performance went unnoticed, the genre won great popularity in the 1950s and continued clandestinely when, due to the war, the theatre company was evacuated elsewhere. After the ceasefire, yeoseong gukgeukfostered popular fantasy and allowed the public to forget the pain of war, yielding unprecedentedly large fandom.

From the 1960s onwards, yeoseong gukgeuk declined as dictatorial regimes implemented projects to nationalise and officialise traditions involving male musicians, excluding it from institutional support.04 It also fell behind amidst the influx of cinema and forms of Western theatre and performance into South Korea. But even though the institution failed to train new generations of actors, the experience of yeoseong gukgeuk for women in the 1950s was beyond a mere escape from a patriarchal society:

Yeoseong gukgeuk provided women with positive experiences in being ‘outside’ at a time when women could not venture beyond the confines of the home. Against gender norms in early modern East Asia that saw women outside the home as potential threats to public morals, yeoseong gukgeuk showed that it was possible for women to perform activities on their own and to create a same-sex community that produced a sense of belonging and commitment for women.05

Yeoseong gukgeuk is thus primarily reminiscent of modern female subjects, who allow for a glimpse into the subjectivity and realisation of women-centred activities. Furthermore, over the past decade the genre has unceasingly provided new inspiration for siren eun young jung, who has treated its engagement with genderqueer epistemology as an unexplored and evolving multifarious organism. What she has found most fascinating are the aged actors who have become living monuments for the queer community. Behind such fascination is a liberating awareness of gender from an open and non-normative same-sex community, as found inside the ambiguous, complex and transgressive yeoseong gukgeuk.

Based on materials, transcripts and video recordings acquired through a long-term exchange with elderly actors, siren eun young jung has presented visual archives in installations such as Public yet Private Archive (2015) and lecture performances such as Gender Bender Fencers (2014 at Arko Art Center, Seoul and 2017 at HKW, Berlin). Within these archives, her interpretations intervene in intimate accounts based on the actors’ oral testimonies, a photograph of a simulated wedding between a nimai (lead male) actor and a female fan, and images of actors impersonating characters who are blind in one eye or staging swordfights. In so doing, she invites the audience in to vivid scenes of homosocial intimacy, which include emotional rapport, passion, sexuality, friendship and affection among women, all common in the little-documented yeoseong gukgeuk community. 06

In The Masquerading Moments (2009), the artist focusses on the face of an elderley nimai actor. As they put on theatre make-up the performer exists as a gender- and age-fluid being. In works including The Unexpected Response (2009), A Masterclass(2010) and Lyrics 2 (2013), the artist presents body-transgressive gender performances – recalling the notion of ‘gender-becoming’ – while video records the actors’ training in ‘masculine’ acting based on pansori dances and songs. These works are precursors to her latest works, which have moved on to the bodies of queer performers and performance aesthetics.

Pansori is a premodern, traditional genre of vocal performance in Korea that was used to recount the nation’s traditional tales in outdoor spaces, or in banquet rooms in traditional houses. In yeoseong gukgeuk it is combined with Western proscenium theatre performance, and features women actors only. The artistic community training in and performing this traditional art embraced non-heterosexual relationships and imagination, enjoying complex gender performance without the discriminatory perspectives or exclusions that are based on both Confucian and modern heterosexist gender ideologies. This fascinating and liberating liminal space aroused a powerful imaginary as it transcended the dichotomous ways of establishing boundaries – such as tradition/modernity and female/male – that existed during Korea’s transition into a modern society. It is the basis of an epistemological break liberating us from conceptions of Asia’s traditions and premodernity only as ‘delusions’ or ‘oppression’, with the West positioned as the norm. In other words, siren eun young jung’s yeoseong gukgeuk works recognise and realise tradition as a liberating threshold and a space of potential intermixing. Such a tradition calls into question relationships of self-denial, conflict and antipathy towards Korean customs, which have previously been seen as colluding with statism and heterosexism while maintaining the oppressive narratives of the Confucian patriarch.

Such a tradition calls into question relationships of self-denial, conflict and antipathy towards Korean customs, which have previously been seen as colluding with statism and heterosexism while maintaining the oppressive narratives of the Confucian patriarch.

Since 2012, siren eun young jung has expanded on her previous methodology in video, creating outstanding works that transform yeoseong gukgeuk into contemporary stage performances, based on her insight into the practice. In the ‘docu-stage’ work Off/Stage (2012), veteran actor Young Sook Cho (조영숙), a long time sammai (삼마이, supporting male) actor, recounts her involvement in yeoseong gukgeukand tells anecdotes from her life as a performer, along with a presentation of old photographs. She also laughs, dances and sings, expressing her talents as a National Intangible Cultural Heritage skill holder. 07Masterclass (2012) wittily stages the illusiveness of biological ‘masculinity’ through a 30-minute performance that dramatises an acting training process based on the representation of ‘maleness’ by Deung Woo Lee (이등우), a female second-generation actor who has played leading male roles, along with her pupil. These works are fully-fledged occasions for siren eun young jung. Not only are elderly actors, used to repeatedly performing hackneyed, outdated and conventional narratives, transformed into the bodies of a vivid, non-normative archive on contemporary stages, but the artist herself is expanding her repertoire to works for the theatre played at performance festivals across Asia.

Anomalous Fantasy (2016–ongoing) is a 1h 25min theatre performance on precarity and deprivation, expressed through the melancholic confession of Eunjin Nam, a young nimai (니마이) actor training in the yeoseong gukgeuk tradition. Oscillating between the frustration and possibility of both the queer, ‘camp’ sensibility and the liberating and non-normative mentality that vibrates within the culture of yeoseong gukgeuk, siren eun young jung gradually replaces the lethargy of a tradition with the songs and dances of an amateur gay chorus, they sing to diverse pieces of popular music, and moving with the sense of empowerment made possible by yeoseong gukgeuk and its genealogical imagination. This stage work attempts both to re-inscribe the minority position of LGBTQI+ people in the centre and to queer all norms regarding traditional performances/stages as well as representations of professionalism and gender. More fundamentally, it ponders the unstable positions of Asian traditions and of the queer, in particular via Deferral Theatre (2018).08 Here siren eun young jung confronts the personas of Minhee Park (박민희) – a renowned performer of gagok (가곡, Korean traditional vocal poetry and singing genre), grappling with the narrow possibility granted by tradition; Azangman – a drag king performer who discovers their authentic self through queering; and the melancholia and modulation of gendered identity of Eunjin Nam, the remaining male-role successor of yeosong gukgeuk. In doing so she emphasises the potentiality that the decline and instability of yeoseong gukgeuk in fact open up:

By creating a triangle of Eunjin Nam, Minhee Park and Azangman, I did want to show how they needed mutual support in such [an] exclusive and disadvantaged genre and how there had been such struggles. I thought that performativity on stage has its core in the ‘time’ of their performing, where the problematic topics like tradition or sex gradually show themselves, and that it might be necessary to let movements like questions, challenges and resistances be made about the time. So I’d like to contend that this insufficiency, instability and lack could instead be the resources of imagining a new realm. ‘The queer’ could be ‘in/stability’. When something isn’t completely concluded, naturally named, or given authority that we can create unique kinesthetics. It’s a view that rather than by being given a name by authority, we can write our own history by deferring it. 09

Being adrift due to the denial of one’s authority can give way to resistance or mobility. siren eun young jung focuses on the queering made possible by the deferral of authority and the non-normativity of a discriminated-against position. The artist stresses that she approaches yeoseong gukgeuk from the context of queer performance not because of the queer identities within that community, but rather ‘because it lets us constantly question how queerness can be performed, and what its aesthetics as forms and styles are’. 10

At last, A Performing by Flash, Afterimage, Velocity, and Noise is a work that fully addresses the aesthetics of queering inherited from yeoseong gukgeuk. The performers’ bodies are mobilised, and sound and light elements inherent to the medium are pushed beyond their conventional range, which the artist describes as ‘exploiting’ the medium. The immersive screens on the three walls that completely fill the room emit intriguing sensory stimuli such as vibrating sounds and extremely slow or fast-paced rhythms. Screens smoothly expose the disparate bodily senses and the intriguing disharmony of the performers. In this situation, however, stimuli never exclude the viewers. Rather, the work wonderfully invites them to a moment of being one with the breathing and dancing of queer bodies. Caught off guard, we face moments that move our hearts amidst KIRARA’S music. The sensory overload that siren eun young jung mobilises in this work constitutes a bold, vibrant action, towards campness and unevenness, and towards one’s own anomalousness and enchantment; it is a celebration of one’s own non-normativity. Transgender musician KIRARA’s 135-bit sounds collide with or lead the performers’ movements whose (im)perfect performing bodies clash with their worlds. This queering of video draws out a transformative moment to which viewers can naturally surrender together to the beat. One finally comes to realise that what always and truly makes us dance lies in nothing else but the emancipatory moment found in utterly anomalous, utterly queer enchantment.

Footnotes

-

Anomalous Fantasy was first performed in Korea in 2016 with subsequent versions in Taiwan (2017), Japan (2018–19) and India (2018), and again in Korea in 2019.

-

Pansori is a folk music genre unique to Korea where, to the accompaniment of a gosu (drummer) playing jangdan (rhythmic patterns), a singer orally performs narratives, interweaving them with sori(singing) and aniri and adding ballim. Aniri refers to the saseol (narration) uttered between songs without adding melodies, as if talking; and ballim refers to gestures made with the body or the hands in order to aid in the dramatic development of the singing.

-

siren eun young jung, ‘A Brief History of Yeoseong Gukgeuk: Birth and Decline’, Trans-Theatre (ed. s. jung), Seoul: Seoul Forum A, 2016, p.201.

-

See Ji Hye Kim, ‘1950 nyeondae yeoseong gukgeukui danchehwaldonggwa soetoegwajeonge daehan yeongu (A Study on the Troupe Activity and the Declining Process of 1950’s Female Gukgeuk)’, Journal of Korean Women’s Studies, vol.27, no.2, 2011.

-

s. jung, ‘A Brief History of Yeoseong Gukgeuk’, op. cit., p.204.

-

Homosocial, same-sex intimacy was the concept used by gender culture scholar Ji Hye Kim in her article ‘1950 nyeondae yeoseong gukgeukui danchehwaldonggwa soetoegwajeonge daehan yeongu (A Study on the Troupe Activity and the Declining Process of 1950’s Female Gukgeuk)’ in order to explain the level of gender complexity in the yeoseong gukgeuk community found in studies on the female subject of this genre.

-

The Korean government has officially announced and protected Intangible Cultural Heritage since 1964. According to the National Intangible Heritage Center in Korea (https://www.nihc.go.kr/eng), it refers to traditional cultural heritages where human performance is a medium, for example Pansori(traditonal Korean vocal performance) or Talchum (Korean mask dance). In contrast, tangible heritages refer to historically valuable inheritance or relics like tombs, pagodas, statues of the Buddha, pottery, books and so on.

-

The work was created on the occasion of her receiving the Korea Artist Prize from South Korea’s National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA) in 2018.

-

Ágrafa Society, ‘Interview with siren eun young jung: Re-formation and witnessing of performative languages’, Seminar [online journal], no.2, available at http://www.zineseminar.com/wp/issue02/interview-with-siren-eun-young-jung-re-formation-and-witnessing-of-performative-languages (last accessed on 18 November 2019).

-

Ibid.