I have an oddly ambiguous reaction to the cuts in public funding for culture currently proposed in the Netherlands. On the one hand, I deplore the short-sighted stupidity of a neoliberal government that wants to keep its racist partner happy by cutting what it refers to as a ‘left-wing hobby’. On the other hand, I can’t help but see the cuts as part of the necessary retreat of Europe and eventually the United States from their dominant world position. The cuts, which I think will be mirrored in many other Western European countries, are targeted at contemporary cultural production, discourse and international exchange. Under the new budget, the Netherlands’s big museums remain fully funded but some 50% is taken from the smaller R&D sector in the so-called visual and performing arts (the Dutch government still sticks to these archaic divisions). The new budget thus gives way to the familiar while expecting the private sector to pick up the tab for the experimental, the challenging and the minority. If ever there was upside-down thinking in terms of simple market economics, this is it.

Yet, without being able to prove it conclusively, I sense that there is majority support for such cuts among the Dutch population. Many see it as a way to hit the media and culture elites who promote their emperor’s new clothes, as contemporary art is often described. ‘Let them survive in the real world’ is the cry, as though the richly subsidised mortgages and tax breaks of the Dutch upper middle class are somehow natural phenomena. For others, there’s much more a feeling of resigned inevitability about the cuts. From a position that might consider itself ‘Dutch leftist’, in the vague sense of being concerned about opportunity, fairness and tolerance, there hasn’t been much effective critique of the economic and social policy of this neoliberal government. I suspect that is because, speaking from that position, there isn’t much to say. The kind of well-meaning social democracy that wanted to make the world ‘better’ and could do it from a safe European home is simply not sustainable. It’s core beliefs – in a united Western Europe, in a homogenous national society of engaged citizens, in cultural toleration and political consensus – just don’t seem to press anyone’s buttons anymore. However nostalgic we may be for these once ambitious aims, they are no longer on the political table. The wealth stockpiled in the glory days of empire, the wellspring of post-1945 openness, grounded on the idea of ‘never again’ to National Socialism, the principle of hosting without hospitality that permitted non-Dutch to live in the Netherlands in peace – these are all running dry. In its place is a world in which there will be no space for such delights as subsidised art and culture, subsidised health care, unemployment benefits – or at least not as much as there used to be. It becoming clear that this long-term settlement has to change. To be meaningful, even useful, again, art has to occupy a different role in an atomised society, where the public interest needs to be redefined and given force in these new circumstances.

Yet from the mainstream ‘left’, the response to this situation is more akin to a rabbit staring into the headlights than a political programme. ‘Keep as much of the old system as we can, while we can.’ ‘Just survive another day with the old welfare state we so slowly built up, in case something absolutely unexpected might still turn up to rescue it all.’ That’s about all I can discern behind the empty rhetoric of opposition – and even the Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) play this game. Probably, from a hardcore social democratic point of view, this grasping at straws is reasonable. But it won’t take us anywhere we need to go.

The reason for this is the deeper malaise that underlies the leftist anxiety about change – a malaise which these current neoliberal cuts try to answer in their own class-ridden way. The post-1945 ‘natural’ order that infused much economic debate and the post-1968 order that did the same for social values have fallen apart. They no longer command a consensus and certainly offer no vision of the future worth rallying for. All of us living here, working here, sharing this culture, know that their decline has set in for good. This scares many native Europeans, and understandably. The world that is emerging is a not a cosy, North Atlantic one anymore. The peoples of the old ‘third world’ are becoming the subjects of history, as Lenin predicted almost a century ago, and they will rightly disrupt familiar patterns of life and confirm new elites that will impose their globalisation on ‘hard working’ Caucasians. This is probably going to be far less disruptive and far less foreign than European colonial impositions once were. Europe has the advantage that it trained the world and made it one in the first place, so it is likely to always have some special privileges. They just won’t be as great as they were over the past few generations.

As a cultural agent, I feel there is a deep, almost unspoken agreement that this is what is happening on a global scale. Its effects can be seen in a largely retrospective culture: a culture interested in repetition and analysis of what once was; a culture more attracted to quantifiable effect and diversion than speculation; at its worst, a culture grounded in cynicism and opportunism. And this culture, in my understanding, is also the emotional foundation upon which an acceptance of these cuts is built.

Yet, despite the justified decay of European hegemony, I do not embrace these cuts but oppose them. If I could wish for the world, I would wish that we abandoned the left as the historic category born in the French Revolution and instead began the task of building a planet-wide political movement. That movement would need to discipline and control global capital but not destroy it; it would need to express a desire for global cultural institutions and find ways to construct them with public money across the continents; it would need to encourage the transfer of wealth from rich to poor to raise world educational standards at levels from primary school to university; it would need to keep the nation-state in check but encourage hugely diverse and hybrid cultural identities. I also have absolutely no idea how I can express these views effectively in the current circumstances. My position, again, seems to be a marginalised one within the opinions circulating in the Netherlands’s democracy.

So, in the end, my refusal to endorse cuts is based on poetry, that minority cultural form that has long required patronage to find an outlet into the world. My guide then is Dylan Thomas. Writing about old age, like an old culture, he commands, with characteristic musicality:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rage at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.’01

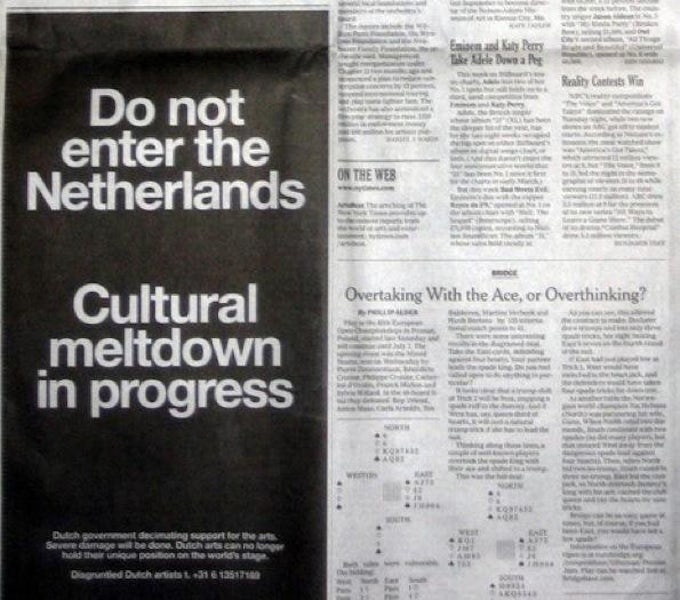

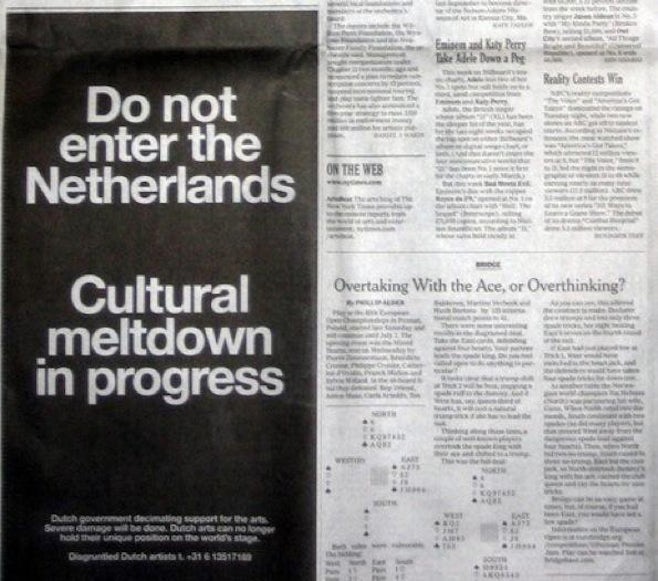

Following Thomas therefore, in rage but also sorrow, I wish the Dutch government and its clownish minister of culture Halbe Zijlstra nothing but failure, distress and collapse. I will not go gentle into their good night.

The original version of this article will be published in Dutch as a special edition of OPEN journal together with De Groene Amsterdamer edited by Sven Lütticken and Jorinde Seijdel, SKOR, NL, September 2011. Image via The Creator’s Project.

Footnotes

-

Dylan Thomas, ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night’, from The Poems of Dylan Thomas, New York: New Direction Publishing Corporation, 2010. pp.52-54