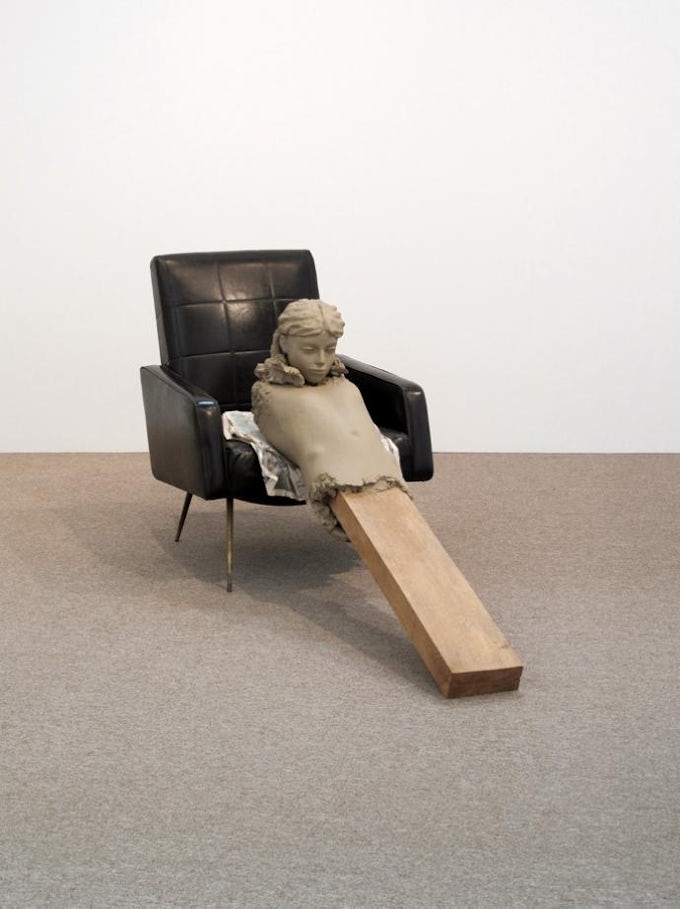

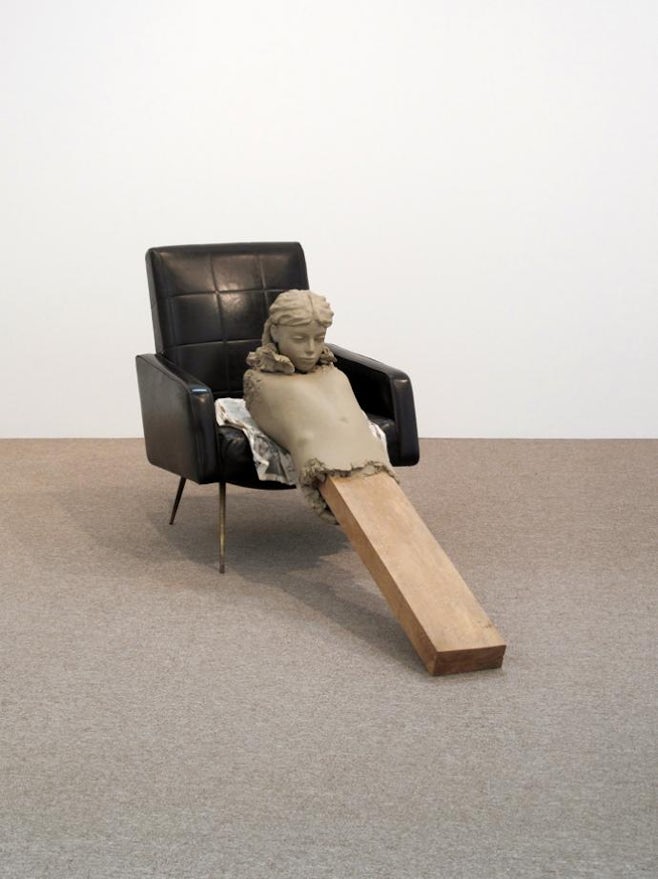

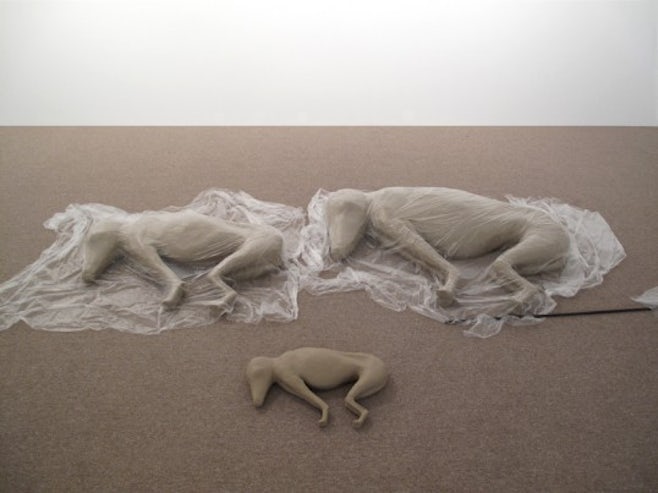

The works of Dutch artist Mark Manders present a number of possibilities for viewers. On a material level, his sculptures and installations appear as carefully constructed assemblages of furniture, human and animal figures, newspapers, networks of welded metal piping, tea bags and other ephemera of daily life found in his studio and on the street. They are conceived as artefacts that would be found in the rooms of his Self-Portrait as a Building (1986-ongoing), an ever-expanding parallel super-structure created by a fictional alter ego whose artistic production and obsessions inform Manders’s own, while never fully converging as a true autobiography. Manders’s sculptures can also be read as poems that have been freed from the strictures of language and whose concrete physicality belies traces of ghostly afterimages and waking dreams. Having made a decisive turn from poetry to art when he was a young man, Manders’s inventive relationship with language is also revealed in the poetic and precise manner in which he describes his artistic practice. An exhibition of his recent sculptures,‘Parallel Occurrences/Documented Assignments’, is currently on view at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, and will travel to the Aspen Art Museum, the Walker Art Center and the Dallas Museum of Art.

AUDREY CHAN: What was the genesis of your project Self-Portrait as a Building?

MARK MANDERS: In 1986, I met someone on the street and it was love at first sight. From that moment onward I started making a building. I wanted to make a place that could be visited.

AC: A building can take many forms, such as a home, a shelter, an office, a factory or a machine. Can you tell me more about the nature of the ‘building’ in your project, especially as it’s represented in your work, Two Interconnected Houses (2010)?

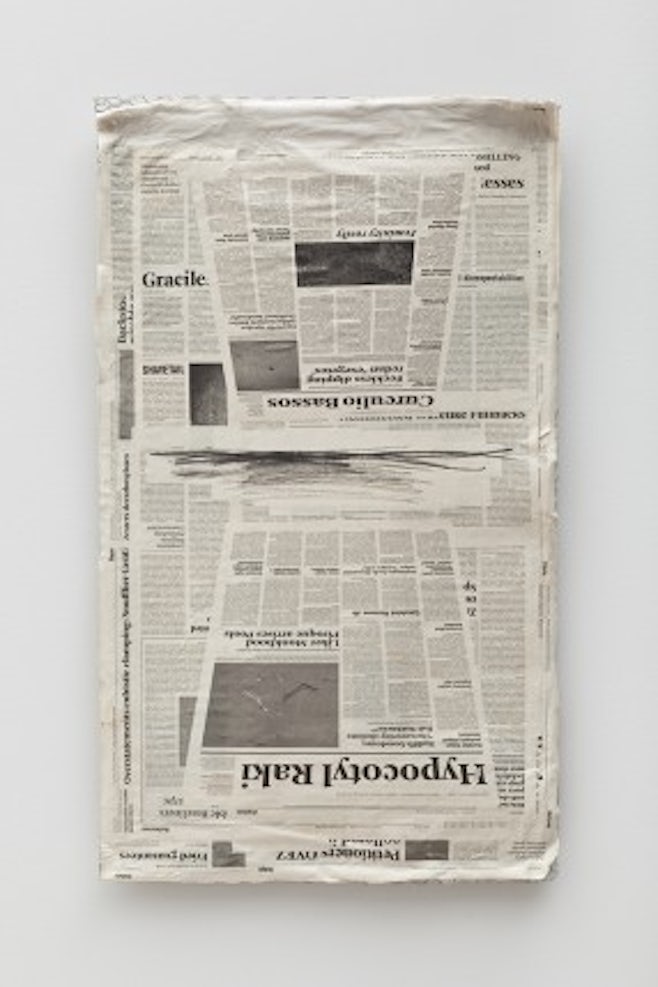

MM: Well, it is a self-portrait – not a home, office or shelter. We know that language can function as a machine and that that does not only happen in the written works of Raymond Roussel – I think it counts for language in general. The moment I embarked on my self-portrait I also became part of a machine. I like to think that I can make decisions in my work but the truth is that I am just following the logic of what I once started. The work Two Interconnected Housesbegan as a project for the ‘Contemplating the Void’ show at the Guggenheim in New York. For me it is a healthy in-between project, like a small and great holiday. It became a slide-work of pictures of two houses that are interconnected underground by two tunnels. These two houses now function as one house. One tunnel goes from one kitchen to the other. All the windows in the house are covered with fake, self-made newspapers. I used photographs taken in the old Jewish school in Berlin, the location of the 4th Berlin Biennial, to construct the rooms.

AC: There are two Mark Manders in your practice, the person I’m speaking with, and ‘Mark Manders’, your artist alter ego. Why do you maintain this dualism?

MM: I think it is very logical to make your work in the first person, especially when you have decided to create a self-portrait in the form of a building. And then again it is logical that that person who creates and inhabits that building should share the same name as me.

AC: Do you envision working on Self-Portrait as a Building for the rest of your life?

MM: Yes, that is what I decided when I was young. Creating a small space where you project your thoughts can at the same time generate a lot of possibilities and freedom.

AC: Tell me about your studio.

MM: I work in the small town of Ronse, Belgium, in a huge factory with a lot of space. Most of the time I work alone without assistants and I work on many pieces at the same time, probably more than thirty.

AC: Your father, a former furniture designer, works with you on the fabrication of some of your sculptures. What role does he play in your artwork?

MM: My father plays no role in my work. He sometimes just helps me practically. For example, he helped me with the production of the two chimneys for the work Room with Chairs and Factory (2002-08). He also reduced all of the furniture to 88% scale for my installation Reduced Rooms with Changing Arrest at Documenta11 in 2002.

AC: How did you come to incorporate furniture, such as tables and chairs, into your sculptures?

MM: It is very logical that my work has domestic aspects. Even when I make landscapes, they are landscapes that are part of living rooms. A house is made with only a few words: table / corner / typewriter / chair / wall / shoe / kitchen…

AC: I am intrigued by your sculptures that include elements in cast bronze painted to look like wet clay. Can you tell me more about them?

MM: In 1992, when I made Fox/Mouse/Belt, my first work in bronze that I painted to look like wet clay, some people thought I was crazy for making a figurative work at that time, crazy to make a work in bronze and crazy to then paint it like wet clay. Some people wanted to cover this bronze piece with plastic to protect it from drying and cracking. I wanted the work to seem like it had just been made – just left behind by the person who made it. All my works are frozen together in one big ‘super moment’. These wet clay works look very vulnerable, fragile, and changeable; it doesn’t really matter if they are made in bronze. If you make a figurative work it is fundamental to use wet clay. You can also freeze sand together, or use dust. But the most logical material is wet clay. As I’ve said in a previous interview, I don’t want to use my material symbolically but in a more actual and direct way. I don’t want to say, ‘This material stands for this or that meaning or for this or that personal interpretation of the meaning of the material’, because that creates an annoying and evasive illustrative rebus that requires too big a detour around language.01 I prefer to use reality and its rich infinite vocabulary.

AC: In your mind, what does a sculpture do that language cannot, and vice versa?

MM: Objects drop shadows and that does not happen with words. I like the way that objects can generate thoughts in a mind. It is much more complex than the way that happens in language. Also, objects relate physically to your body when you look at them. If Kafka writes a line, the reader reads that line and then the next one, etcetera. He directs you in what to think and in what order. Sculpture has another great relationship with time. It is composed of frozen thoughts that are frozen together in one single moment and yet it takes time to circle around it with your mind.

AC: Do you think it is ultimately a futile endeavour to use language to approach artistic meaning?

M M: No, in principle you cannot say that. Writing about a work of art can possibly become a work itself.

AC: In addition to your art practice, you run ROMA Publications, a small publishing house where you produce artist’s books. What inspired you to start making books?

MM: In 1998, I became friends with the designer Roger Willems and we started to make books together quite naturally. Werkplaats Typografie offered us a desk in their institution for two years so we just started producing books and it was kind of addictive. It is much more interesting to make books directly with an artist, without museums interfering. You can think quickly, clearly, and without the restrictions of a big institution. If we want, we can also think slowly and create many restrictions for ourselves, just to get to the point we want.

AC: For you, what is the difference between experiencing artworks in a book versus in an exhibition?

MM: There is an interesting relationship between an artist’s book and an exhibition. I also think that since the internet has gained so much volume, the artist’s book has become even more interesting. A book is a great concentrated location for creating an exhibition. The linear relationship with time in a book is fantastic and powerful. Also, the relationship with the public is interesting. Most viewers of an artist’s book own the work and choose their moment of visiting. And artist’s books are small and cheap – they don’t take up much space, and in a way it is good that the medium is underrated and sits under the radar of the commercial art world. For me, the relationship between an artist’s publication and public space is also very interesting. In 1999, we published my Newspaper with Fives in an edition of 150,000 copies and distributed them house-to-house in the German city of Hann. Münden. I used the doormat or the mailbox of someone’s house as a public space. I don’t often show my work in public spaces, rather mainly in museums where people choose to go to see art. But since 1991 I always test a work that I’ve just finished in a supermarket. I just imagine a new work there and I check if it can survive where it doesn’t have the label of an artwork. It is just a thing that someone placed in a supermarket. Now I am sure that all of my works can stand in that environment. In 1993, I actually showed a work in a supermarket as part of my work in the Sonsbeek 93 show.

AC: Are there artists or art historical periods that serve as touchstones in your work?

MM: In the 1980s, I became very interested in Renaissance painting and that has never stopped. During art school, Lucas Cranach had a big impact on me, and I am very interested in painting in general. But of course an important base of my work is Minimal art and Conceptual art. It’s great to take the next step from there and I am very grateful to work in this period. It is a pity that not many artists realise what a great area has been flattened out before us. There are a lot of things we don’t have to talk about anymore. I guess all has been said about institutions, we understand what a museum is, how thin a work of art can be, etc.

AC: Finally, if Mark Manders (the man) were to ask ‘Mark Manders’ (the artist) any question, what would he ask?

MM: In the end, when I die, do we then come together as one?

Mark Manders’s exhibition is on view at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles until 2 January 2011.

Footnotes

-

Interview with Marije Langelaar, ‘Room, Constructed to Provide Persistent Absence’, in Mark Manders/Singing Sailors, Toronto and Amsterdam: Art Gallery of York University and Roma Publications, 2002, p.35.