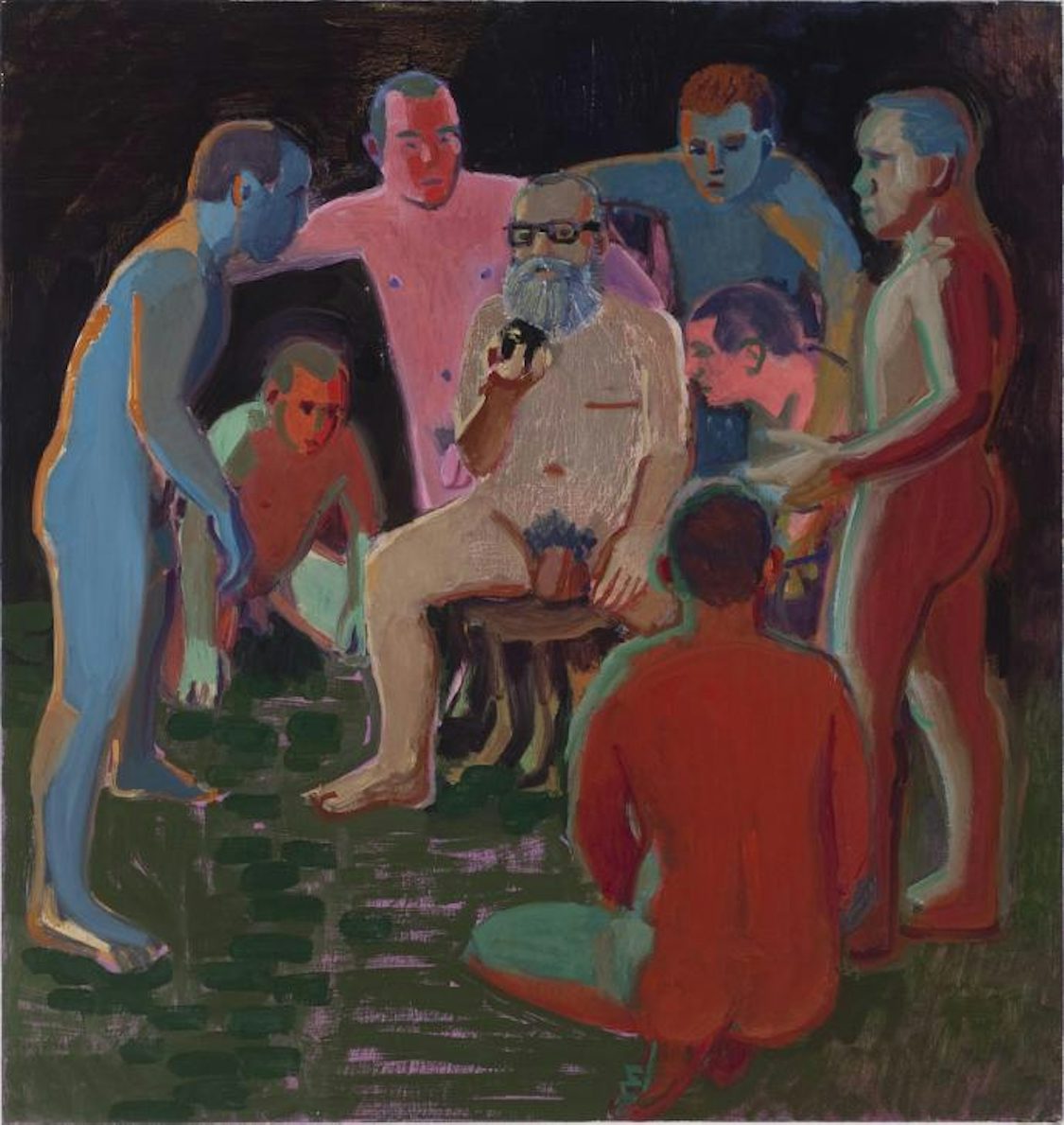

AA Bronson is an artist and healer who co-founded the seminal art collective General Idea in 1969. Felix Partz, Jorge Zontal and Bronson of General Idea lived and worked together for 25 years. [Partz and Zontal died in 1994.] Bronson continues to work and exhibit as an independent artist. Recent activities include Invocation of the Queer Spirits (2008-10), a project series in five cities, and various initiatives that explore art and religion through the lens of social justice at The Institute for Art, Religion and Social Justice, a project he founded under the auspices of Union Theological Seminary, New York in 2009. He recently resigned as President of Printed Matter, Inc. and as Director of the NY Art Book Fair.

This interview centres on the theme of education, which artist Sissu Tarka is exploring for two projects, Artschool UK – which activates, processes, stages and performs a model of self-organised art education01– and the second edition of Collaborative Futures, a collaboratively authored book about the theory and practice of collaboration, with a focus on social media and peer-production.02On this occasion, coinciding with the spring issue of Afterall, which explores questions of pedagogy, and considering the recent debates about de-schooling, the interview with Bronson in New York, June 2010 provided a chance to look at historical and contemporary alternative approaches to art education.

his is an extract from an extended conversation that will be published in the Artschool UK publication. It affirms the need for maintaining a site for inventing, activating and practising creating against ‘the product’, and to look aside for bringing different issues, such as social justice, into a kind of protective zone of art.

SISSU TARKA: I’m interested in your practice in relation to the multiple and collaborative roles you acted out very early in your work, prior to, and perhaps differently to what’s going on now; for example, offering platforms for other artists as with the early publishing and distribution centre Art Metropole [of which Bronson was a founding director], the setting up of school and communal projects and your work with or on your mirror self – that is, your mirror self portraits03 – which leads more into your actual artwork as well.

AA BRONSON: The subject of schools is especially interesting for me. When I was in university studying architecture, in the second year I dropped out with a group of friends, to set up our own free school and commune.

ST: When was that?

AB: That was in 1967, I think, around that time. And I don’t think the school was very successful – it only lasted one year. But because of that, people started to invite me to speak at conferences on radical education and free schools, which of course were very of that moment.

ST: Similar to now in some ways.

AB: Yes. It was a very active moment and there was a magazine called This Magazine Is About Schools, published out of Toronto (it launched in 1966), which was about radical education and free schools. And then as recently as this year (2010) I planned to teach a residency at the Banff Centre in the Canadian Rockies called AA Bronson’s School for Young Shamans, which was to be set up in the same kind of way: the group of people who were participating as students would actually form the syllabus and provide a lot of the content. But unfortunately I just cancelled that last month.

ST: I saw it announced on your website.

AB: Forty-five people applied to be in it and I chose fifteen people but I never actually told them because I cancelled it first. [laughs]

ST: Why did you cancel?

AB: Well, I realised that Banff was too much of an institution and that it wouldn’t be able to cope with this kind of project. Banff has wonderful facilities, but the kind of thing I wanted to do was more spontaneous or collaborative. Among the various applications the interesting ones for me were projects that involved themselves in the bigger project rather than being personal. For example, one proposal was to make and publish a weekly newsletter for the School for Young Shamans. Or somebody was going to design a sort of hang-out space, some sort of mystical womb that we could all crawl into and smoke joints or something. [laughs] I couldn’t predict what material and facilities would be needed – we didn’t know. It had to be very spontaneous.

ST: So the idea was also to set up a context for potential new forms of social interaction?

AB: My idea was very simple, that we would meet every morning in a circle, and that we would just go around the circle and talk about where we were personally with the project, and then any thoughts on the project as a whole. And then, day by day, that would move the larger project forward. So we might decide to do collaborative projects, mini projects, we might decide to make a group video that documented the school as a whole, or we might… anything could happen really. And the other idea was every evening to have a kind of ritual that would be led by one of the students, anything they wanted – something performative but a group activity, a performative group activity that would be different every evening, for after dinner. [laughs] After dinner entertainment, right!

ST: But do you see yourself within the school in terms of an authority, like a hierarchy, in this free school? In what way would you describe your position or place?

AB: I would be a kind of facilitator, I guess. On the one hand I’ve had a lot of experience with this kind of school environment, and I know a lot about it and I’ve made a lot of mistakes in my life so I know what to avoid. [laughs] So I see it as horizontal as possible, I think my role would be more as a kind of figurehead, a kind of image that people could group around.

ST: More like an icon or a certain personality?

AB: Yeah, it’s probably because of me that people would apply, but then once they’re there it almost doesn’t need me anymore, except to listen. [laughs]

ST: But your presence is definitely important. Do you believe that models and forms of self-teaching or being self-taught work in some ways – for an artist, for art now?

AB: I think so, completely. But then I am biased because I am more or less self-taught myself. I taught for three years at Yale, and it seemed to me that in the context of a master’s program like that, the education is so incredibly narrow and limited, I don’t think it’s really working anymore. Maybe it’s working for the marketplace – it produces artists who can produce collectables for rich people – but for culture, the larger idea of what culture is about and what artists are in relation to culture, it seems to me a waste of time.

Do you know the artist Fritz Haeg? He has a geodesic dome in LA. It’s obviously inspired by Bucky [Buckminster] Fuller. He does all sorts of strange programmes in it – both community programmes and yoga classes. For one year he did a free school, and the school was one day a week for a year. You would go for one full day, and then you would have six days to think about what you’d done, and then you would come back the next week for another day. In terms of what you’re thinking about [with the Artschool project and Collaborative Futures], Fritz is really amazing.

ST: It’s interesting, this school system of one day a week over a long time. And then in the middle or in-between you have your own space and life and set of practices. That’s quite nice I think, because it offers some continuity and simultaneously there is some interruption.

AB: I have a little publication by Haeg that Printed Matter just published. These are various projects, and each page shows a different kind of project. He has stopped it now because he’s got a residency in Rome for a year, but he’s very interesting, much younger than me but basically trying to do similar things in a more contemporary way. Los Angeles has a lot of this kind of very alternative activity going on. And there’s not really any way to find out about it, it’s sort of more of a grapevine.

ST: What do you think in terms of your future, your next projects, do you have certain plans or directions?

AB: To a certain extent. We were talking about the School for Young Shamans that was supposed to be at Banff, then I tried to organise a shorter version at a gallery called Plug-In ICA in Winnipeg. Originally they wanted to do it next year and I said, ‘No, I want to do it right now’. But I was too ambitious; we’ll do it next summer for two weeks. It is a cross between a free school and an intentional community but with a beginning and an end.

ST: There’s also The Institute for Art, Religion and Social Justice?

AB: Yeah. It’s another big project, a project I invented at Union Theological Seminary, together with my collaborator Kathryn Reklis. It’s an unusual seminary, first of all it’s not Catholic or Anglican or Lutheran, it’s very open – it’s Christian, but it’s open. And consequently they have a lot of women studying, a lot of Roman Catholic women because, of course, they’re not normally allowed in a Roman Catholic seminary, so it’s become a big centre for feminist thought. It’s also very racially mixed – it’s about a third black – and so it’s also a major place for liberation theology and ideas around poverty and race. It has a big interest in social justice. The school has been around for about 160 years and has always been a kind of alternative school. The students, pretty much the same as most seminaries, tend to be in their early twenties, but with seminaries, there’s always people around my age as well. People who come later in life as well as people who are earlier in life. It’s academically a very good school. I felt this call to study this material, Christianity is probably the only religion that I haven’t studied [laughs] over my lifetime.

The first thing I noticed was that they knew very little about any sort of social justice work in the art world, so I proposed beginning this Institute as a way to create a conversation between the art world and the world of Christianity. The art world is so suspicious of the Christian world. Tibetan Buddhism is fine but not Christianity.

I find that Union Theological Seminary is very important from the point of view of a more invisible or alternative site of or for art. Also in relation to the queer community, which is, I think, the biggest, or most active, alternative community in the art world, and the most interesting – especially women within that category. A lot of the teachers at Union are women, and they teach from a very feminist perspective. For example, Jesus on the cross is represented as an image of childbirth, the blood and the pain and the giving birth to new life, and only women present – all the disciples having disappeared – there’s only the women and Jesus and this bloody, painful event. I find that picture of childbirth completely fascinating.

ST: Yes, but do you think it has to do with that art itself is a belief system?

AB: In a way it’s a kind of replacement for Christianity. At the same time I wanted to create a dialogue, so, for example, in the fall [2010] I am doing a series of artist lectures, which will also be open to the public, but which are aimed at the students. So far it will be Gregg Bordowitz, Paul Chan, Alfredo Jaar and The Guerilla Girls.

I am also curating an exhibition called ‘Social Justice’ and want to work with younger people who are not so known, doing these strange kind of community projects. I am really interested in people who use a lot of found material or documentation, and for whom this is more of an activity than a product. My idea is to have vitrines scattered through the school and each artist will use a vitrine to display a single project or idea. So as you walk through the school you’ll see the documentation of these different activities

ST: How do you find those young people?

AB: They find me. I’m in this kind of special position, because they do find me, they look for me somehow. And I guess I’m known to be relatively accessible and make time to see people as best I can, like you. And it’s more interesting for me to be involved with younger people and with all this activity that’s going on right now, and it’s also interesting how invisible a lot of it is.

Footnotes

-

Artschool UK is a project by John Reardon, Sabine Hagmann and Johannes Maier, bringing together an international group of artists, curators, designers and critics. Using the formats of workshop, seminar, debate, website/blog and publication (forthcoming), the ‘school’ migrates from temporary manifestations towards a more permanent, yet transforming and accumulative site of art-knowledge polarities and transfer. http://www.artschooluk.org/

-

This second book edition brings together the original six contributors to the January 2010 edition – Adam Hyde, Mike Linksvayer, Michael Mandiberg, Marta Peirano, Mushon Zer-Aviv and Alan Toner – with three new contributors, kanarinka, Sissu Tarka and Astra Taylor, to challenge the free culture sentiment underlying the original writing. It is co-produced by Eyebeam. http://eyebeam.org/collaborative-futures-2nd-edition

-

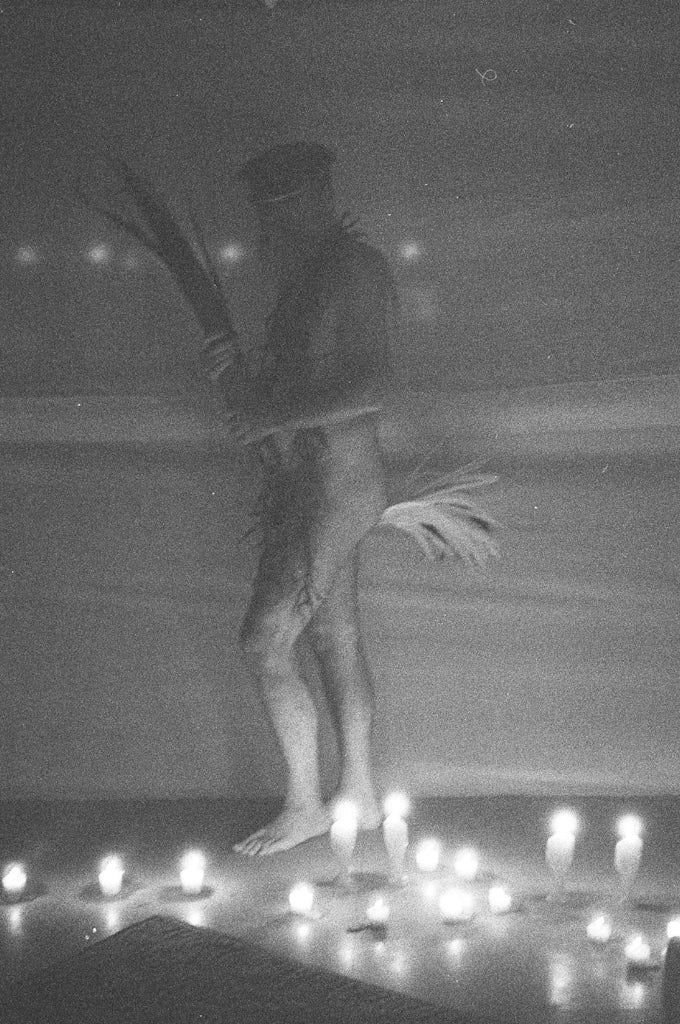

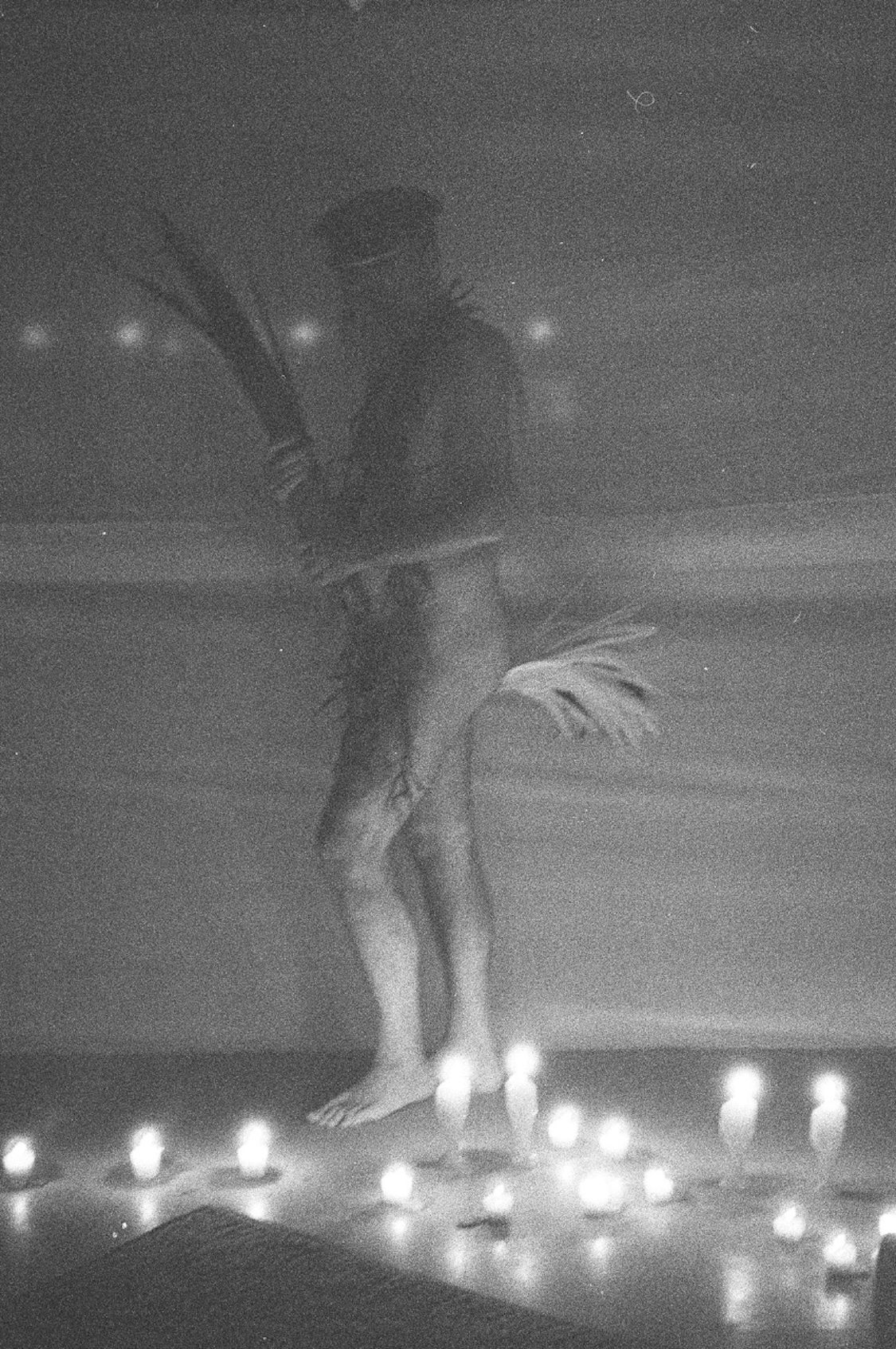

Beginning with the early series Mirror Sequence (1969-70), in which Bronson takes photographs of his own fractured reflection, to more recent works such as a series of life-size self-portraits (2010), silkscreen prints based on his collaborative project Invocation of the Queer Spirits, the artist’s enquiries into the ‘self’ or identity are intrinsically bound up with his surroundings, people, situations, locations, and thus interestingly always also suggest a certain shared experience or image.