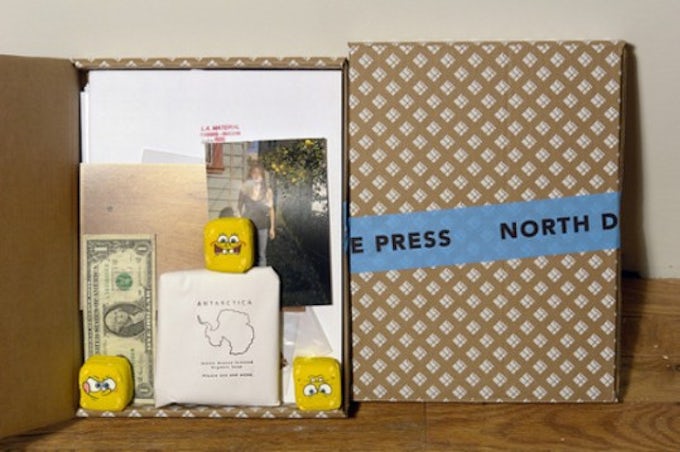

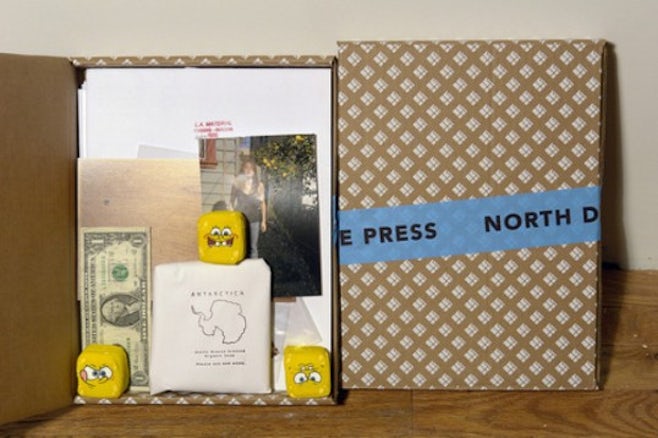

AUDREY CHAN: As an artist publication, North Drive Press is the ultimate confluence of zine, box of miscellany, and collector’s item. Its loose contents can be rearranged and perused at whim, which makes the process of ‘reading’ the magazine open-ended and associative rather than linear, as in a traditional bound format. Your process of soliciting contributors is similar, as it is based on a self-proliferating social network of artists. Has the formula changed with North Drive Press #3 and how do you want it to develop?

MATT KEEGAN: The number of contributors has increased, and since it only comes out once a year, I always want the publication to feel really full. This is the first time that I have worked with a collaborator, Sara Greenberger Rafferty, who is my co-editor. Susan Barber is our design collaborator. It has been really helpful having a co-editor to consider where the project is going – it can be unwieldy with over thirty contributors and no specific editorial parameters. I enjoy the free-for-allness of it; it’s this box of stuff and interviews that doesn’t have strict editorial constraints. There’s no thematic or guiding principle other than people who want to talk with each other or people that Sara and I would like to hear talk to each other. With the multiples, contributors have $500 to make something in an edition of 500, and so the options for what gets produced vary every year. I’m trying to figure out what the role of an editor is for NDP. There’s a great publication called ESOPUS and they have a theme for every issue but the form itself is very rich and there are all these options for printing, interviews, contributions, and there’s a CD and posters. There’s a richness that parallels NDP. I look at that project and wonder what it would be like if our next project were thematic.

AC: Or, because NDP is not thematic, instinct becomes the theme of each issue and it can shift and change at whim. So the organizing principle of the publication becomes centered on the editors’ instincts, bottom-up rather than top-down.

MK: And my instinct is for the project to stay as loose as it is. But I think once there are five issues we should make a book that is just the interviews. North Drive Press is only three years old so there’s always something to learn from it. But I’m excited about how it will continue to change. That’s one thing I love, that it can never be completely predetermined.

AC: You have resisted ‘topicality’ in your choices as editor of NDP, but you also organized a queer-themed panel discussion at Greene Naftali Gallery in New York in December 2003. That event tackled headlong the issue of identity politics in the art world, a subject that gained a foothold in the critical discourse of the early to mid-1990s but which faced a harsh backlash soon after. Given that history, what was the impetus for you in organizing the panel discussion?

MK: In 2003, there were a lot of queer-themed shows and queer-oriented projects in New York. It was as if [the exhibition sites] were saying, ‘We’re in the midst of a conservative administration, so let’s have these shows that are more overtly about same sex desire’. The shows were problematic in a lot of ways, but they were successful in that they were well attended and received a lot of press. But there was no conversation about the fact that, for example, the most talked-about show on television at that time was the reality show Queer Eye for the Straight Guy.Neither was there a discussion of what it meant to have a queer-themed show at that political moment, nor what it meant to have a show that either excluded or barely included a lesbian and transgender contingency. It was interesting to think about a conservativism within those choices. So I organized this discussion in response to the queer-themed shows: Today’s Man at John Connelly Presents; My People Were Fair…, curated by Bob Nickas at Team; and DL: The ‘Down Low’ in Contemporary Art, curated by Edwin Ramoran at Longwood Arts Project.

AC: It is interesting that you mention the popularity of Queer Eye for the Straight Guy because what the show succeeded in doing was so-called ‘improving’ the image of gays in America. In particular, it promoted the message that gay men are nice people and that they can help you, which is distinct from…

MK: That’s the key to that show, that they’re there to help you, not to have individual personalities.

AC: …and that’s different from a public discussion of gay marriage and civil rights in the United States. Reality television ends up being one arena in which gender equality is ghettoized.

MK: That actually led to some interesting conversations about ‘queer dollars’ and ‘gay capital’ or the notion of ‘metrosexual’ as being explicitly about commerce, about buying hair gel and the right shoes. There was some interesting discussion about that monetary connection to queer culture.

AC: Whom did you invite to serve on the panel?

MK: I invited John Connelly; Edwin Ramoran; Scott Hug, an artist and founder of K48; Ginger Brooks Takahashi, one of the co-founders of LTTR; Carrie Moyer, a painter who started Dyke Action Machine; AA Bronson, an artist in Today’s Man and former member of General Idea; and José Muñoz, a curator and professor at NYU who served as the moderator. The transcript was featured in the first issue of North Drive Press.

AC: What was unsatisfactory to you about the way in which queer identity and politics were represented in the shows?

MK: I was part of the Today’s Man show and I saw Bob’s show at Team and Edwin’s show at Longwood Arts Project and I felt like there needed to be a critical discussion of what these shows were attempting to do. I wanted to know what was the subversive potential of these shows when our government was advocating and is continuing to advocate a complete erasure of equality and acknowledgment of same-sex couples and relationships. I had done my undergraduate studies in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Senator Santorum is one of the most vocal anti-homosexual and anti-equal rights politicians in the United States. In the spring of 2003, he made comments such as, ‘I have nothing against homosexuals, but I condemn homosexual acts.’ Basically he is saying that you can be queer, but don’t have sex, just hold hands and go to church. To hear those words and then to go to Chelsea and see a show of beautiful boys made me ask, ‘What is this doing?’ I’m all for something that’s fun and that you can take pleasure in because it is an image that counters such bullshit. In fact, there were lots of people in the audience that said, ‘That show was really fun and we needed that.’ But I also felt that there was a potential for the shows to be just entertainment. Maybe entertainment is not the right word, but the shows themselves didn’t have the collective energy of a forum where people could talk openly about the issues that were raised.

AC: But how do you measure the subversive potential of an exhibition or work of art?

MK: My answer would be contingent on the intentions of the work at hand. At the panel discussion, there was a lot of energy in the room because people were both pleased and upset by the shows. People in the audience were fired up, asking questions like, ‘How can you have a show that talks about masculinity without talking about the possibility for a transgendered body?’ There was a heated discussion about the fact that women and transgendered people were absent from these shows. Also, there started to be a conversation about the absence of artists of color in the Chelsea portion of these projects. We all wanted to talk in a way that was not nice and pleasant – it was a real discussion. That feeling of wanting to talk, feeling angry, and having a passionate response is for me indicative of something, and it speaks of momentum. Something that I like about making art is that, for me, much of it is about conversation and reflection. That desire for something that is not concerned with capital but rather with conversation and exchange, and wanting there to be a space for that; that kind of desire has a subversive potential. It’s tricky because I don’t even know what is subversive anymore… it’s a tricky word. But I also think about dialogue as having a grassroots effect, in that it may inspire and encourage people to continue the conversation further.

AC: Is it also partly an educational project, to organize these conversations in the gallery?

MK: I don’t think of it as educational, but rather about artists and the art-interested talking about what they’re responding to and care about. For example, there’s a project called Scorched Earth that will eventually exist as a magazine and will release all twelve issues at once. Gareth James, Cheyney Thompson and Sam Lewitt run the project. They state their main concern as ‘questioning drawing’s place in theory and practice, which is addressed in dialogue with artists, critics, and historians’. One of their events was a talk by John Miller at Scorched Earth’s storefront space on the Lower East Side. It was very intimate and there was a feeling that everyone could participate. There was no didactic lecture, nor was John put forward as presenter and purveyor of knowledge with everyone else functioning as a passive audience.

AC: That reminds me of your Etc. project at Andrew Kreps Gallery last year, which also explored the idea of audience participation.

MK: Etc. consisted of two group exhibitions, ‘Excitations’ and ‘Talk to the Land’, and a series of twelve events that I arranged. The events ranged from a live light show to all-day events, lectures and a panel discussion. A comprehensive publication is now available that includes transcripts from the talks and images and blurbs on the shows and other events. If your online readers are interested, they can get copies from Andrew Kreps Gallery in New York or from me directly (matt.keegan@gmail.com) for $10.

AC: And this year, you were in Cincinnati, Ohio organizing the first museum exhibition of Public-Holiday Projects, an artist-run curatorial group that you founded in 2004 with Rachel Foullon and Laura Kleger. One of the priorities of PHP is the continuation of a critical discourse that was initiated in graduate school. However, your mission is not contingent on the viewer being familiar with that discourse. How do you reconcile these priorities?

MK: Rachel, Laura and I want the artists that participate in our projects to have more of a voice within the exhibition than they may be allowed in a regular group show. We try to insert into the exhibition source materials and ephemera that the artists may have in their studios or might include in an artist lecture. We also make a publication that accompanies each show, and try to use this space to extend the interests (readings, films, music and others) of each of the artists, so that an audience member can learn more about the behind-the-scenes of the works on view, rather than having information filtered through a curatorial statement or press release that serves a different purpose. As artists, Rachel, Laura and I are aware of the fact that the guiding principles that normally unify artists within a group show (one that is not historically grounded or based on a pre-existing relationship) sets up a theme or foundation that is only relevant for the run of the exhibition. We acknowledge that our groupings are just as temporary, and we try to use additional information to provide a more lasting dialogue between the artist and the viewer and hope for a longer exchange between the participating artists.

AC: I recently visited your two-part exhibition, ‘How to Make a Portrait’ at White Columns and Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery in New York. The show features your father and includes excerpts from a video made by Gerard Byrne entitled Why It’s Time for Imperial Again, in which he was cast in the role of Lee Iacocca, as well as excerpts of a film in which your dad was cast in a small role, but from which his scenes were later edited out. There is also a video, shot by you, of your father on the phone at work remarking to a friend that his artist son is in the room making a video about him. And while at White Columns, I paid a dollar for a copy of the zine that you made with your father, listing recommendations of his favorite restaurants and museums in New York City. It seems like, throughout the project, your father is constantly shifting between object/subject, collaborator, and simply being a dad helping his son with an art project.

MK: His role and presence does shift, and this was important to me. I am interested in my father as a stand-in for the archetypal businessman, the man in the office. Within this two-part show, he is also playing the role of the ‘ex-husband’, a guide to the city that he grew up in, and the more intimate role of my supportive father. As intimate a project as it is, I hoped that there would be multiple places, through cinema, television, as well as through the personal, where a viewer could enter into the project.

AC: How did your father respond to the exhibitions?

MK: I think his first response was the best. After walking into Nicole Klagsburn, he walked up to me and said, ‘I like it, I really like it. It’s weird, but I like it.’ And that’s kind of one hundred percent accurate because it is weird to walk into a room where there are three video versions and a larger than life sculpture of you. I think that he was flattered to have that attention paid to him.

AC: Have you involved your family members in your work previously?

MK: I did a project in the summer of 2001 called Electa Rayon is 90 Years Old. I worked with a choreographer and dancers to create a step and freestyle-inspired dance for my maternal grandmother’s 90th birthday. It was the first time I ever made a video, organized a performance or worked with dancers. The piece was performed at Union Square in New York and also in a high school gym in Manhattan for the video document. I also wrote a cheer for her.

AC: How does it go?

MK: It is a call and response, step-inspired cheer and it goes like this:

Gimme an E!

What? You got your E, you got your E!

Now gimme and L!

What?

I said an L, I said an L!

Another E!

Yo, we got that E, we got that E!

Now gimme a C!

C, see, sî we got that C!

How ’bout a T?

What?

I said a T like Mr. T!

How ’bout an A?

Hey, hey, he we got that A!

So what does that spell?

E-L-E-C-T-A

Electa! Hey, hey! Electa, hey!

There’s no coincidence is sounds…

Electric! Hey, hey electric!

From Cuba to New York, and now in Miami.

Her name is Electa, but she’s known as Nanny.

Nanny, Nanny. Nanny, uh, uh, uh…

5 feet tall, weighs as much as her age.

This 90 year old woman can’t hold her in a cage.

Light as a feather, but stinging like a bee.

You know that’s right if you’re talking ’bout Nanny.

Nanny, Nanny. Nanny, uh, uh, uh…

Golden hair, suits this lady with the Midas touch.

Known for her cakes and such, such.

She’ll sew you somethin’ real nice.

You may wonder at what price?

Just take her to lunch or drive her to church,

She’s not trying to fill her purse.

So fellas!

Who?

I said the fellas!

Oh!

This young Pisces is surprisingly single.

So, break it down, break it down, break it down…

This funky jingle!

At the end of the video, she comes out and dances with the dancers. At Union Square, I received an official permit to allow the dancers to perform for park goers, friends, and family. This was before September 11th, so I got the permit very easily and received access to the gym to shoot the video. It’s a project that would probably be much harder to do now, depending on who picks up the phone in the Parks Department.

AC: You’ve mentioned your interest in the ‘gift potential’ of an artwork. Did you initially conceive of Electa Rayon is 90 Years Old as an art project, a birthday present for your grandmother, or an ideal overlapping of the two?

MK: I like to think of this particular project as a happy hybrid, especially in retrospect. The project was about celebrating Electa Rayon for my family and myself, for the people enjoying the park at Union Square and for the dancers, but mainly for her. I also wanted to create something that most people could relate to, namely the shared experience of having a grandmother. My Nanny’s health declined after that year, so it was the right time to do it.

AC: Given your multiple modes of operation – as artist, editor, curator, panel organizer – I am curious about what constitutes your notion of the ideal artistic exchange.

MK: I am always searching for a balance between my studio-based work and the collaborative projects and publications. They all inform my art practice. I would really love to find modes of exchange that are not so contingent on a commercial market become more common in art. It would be good if art were more integrated into the general culture in the United States, especially through arts funding; but it’s not. So my desire is to be a part of collaborative projects that fill a void that I experience when making work by myself. In collaborative work, there’s the inherent problem solving and decision-making, the arguments and discussions, and basic things like shared labor. I also believe that artists are able to create their own modes of presentation and that there’s an interest in alternative spaces of exhibition and discussion. In New York, it seems that there is a growing audience that wants to see what is available beyond the commercial galleries or to use these spaces to serve multiple purposes beyond functioning as static showrooms.

– Audrey Chan