MONA HAKIM: All of your photographic work, dating from the 1970s to today, concentrates on semi-public interior spaces. You began with domestic interiors but since the 1980s the primary subject matter has been observational or institutional rooms. These are strange, disturbing places, sometimes even menacing. Where does your interest in such places come from?01

LYNNE COHEN: It’s difficult to say, except that I seem drawn to interiors that are strange as well as familiar. I sometimes think they find me rather than the other way around. But what you say is true. Pretty much everything I’ve photographed has an air of strangeness. This is curious, because the subject matter is quite banal – a living room, a classroom, a spa… The strangeness is partly due to the fact that the ordinary is often more menacing than the blatantly bizarre, which can be easily dismissed as impossible. Perhaps it is also because the places are so familiar that they are a bit too close for comfort. In a 1992 exhibition catalogue essay ‘The Scene of the Crime’, Jean-Pierre Criqui links Freud’s notion of the uncanny with my work. The idea is that the familiar, far from being benign, has the potential to be far more unsettling than the unusual. In the same essay, Criqui points to a similar phenomenon in a Kafka story where an inanimate object takes on human qualities in the way that furniture and paraphernalia in the rooms I photograph assume human characteristics.

Yet another thing is that the camera singles out details that do not normally draw much attention and then tends to exaggerate their significance. I should also say that I often find the spaces to be as absurd as the objects themselves. They resemble stages on which complicated stories are about to be played out, though it is never quite clear what story is being told. The incomprehensibility of the narrative contributes to the weirdness. In one photograph with the generic titleClassroom there are some skeletal remains of an animal confined in a wooden cage. This is odd and disturbing. Why does a dead animal need to be locked up? And what is a Naugahyde office chair doing in the foreground in front of what looks like a structure from a religious painting? The chair appears to be giving a lecture. One can only imagine what horrible remains have been swept down the black drain on the floor in front of the chair and why, in the far corner next to the door, there is a pile of hay. A dead animal is unlikely to need food. These are small details but together they create an atmosphere of the uncanny. That interests me. My goal is not to photograph any old classroom. There has to be something, or the accumulation of something that draws me in.

MH: How did you come to make a transition from domestic, kitsch interiors to colder, more minimal, institutional sites?

LC: I understand how some pictures have been construed as a critique of kitsch, but that wasn’t foremost in my mind when I was taking them. I also understand why people take my move to more institutional places – men’s clubs, banquet halls, meeting rooms, classrooms, laboratories – to be a move towards the colder and more minimal. That wasn’t the guiding force behind them either. In fact cold and minimal is not how I would describe them. The shift had more to do with my dislike of living rooms, shag carpeting and such, and coming to realize that I really didn’t have anything else to say about them. I hated being so close to things. Most living rooms are small and it always seemed as if there was only one possible place to make the picture. That bothered me as much as the living rooms themselves with their smells of baby powder and food cooking. It was just that institutional spaces weren’t claustrophobic in the way that domestic interiors were. Another reason I shifted my focus was that I wanted to address more social and political themes and it seemed that if I moved from domestic settings to more public ones, I would be better able to address them. In institutional spaces I was able to get further away from my subjects. The space no longer dictated where I had to stand to make the photograph – there was more room to maneuver. The rooms felt strangely distant, as if I was photographing them from far away.

I should add that I think people are mistaken in believing that my early work can be reduced to a critique of kitsch and later work to a critique of minimalism, cold surfaces or modernism in general. Admittedly many of my early photographs of living rooms record various sorts of taste. But since the pictures were made in the homes of middle class people, university professors among others, it never struck me that the focus was on kitsch. InFamily Room the history of modern art has been appropriated and we see a Frank Lloyd Wright flower box, a Mondrian bar, a Jeff Koons Playboy Bunny, an Arp coffee table, a Braque reproduction and an Artschwager wood-paneled wall. The linoleum floor looks like a lyrical abstract painting and the scale of everything is wrong. The room ends up looking like a doll’s house and there is no clue as to how one might get into or out of it. I can understand how this photograph could be seen as a critique of kitsch but that was not what drove me to make it. I was more interested in the odd scale, the fact that the room has no exit, the three-dimensional demonstration of modern art and the way the interior architecture looks like it is constructed out of foam core.

MH: Getting permission to photograph some of these places – particularly the laboratories, observation rooms, military installations and thermal establishments – seems to be a feat in itself. How do you go about doing it? Has this notion of challenge become an important condition, or even an intrinsic condition, to your artistic approach?

LC: Yes, the process of getting permission is, an intrinsic part of the work and has been an enormous challenge, even struggle, from the start. There is something about this process, which often strikes people when they first see my work. Although there is no trace of my presence, the pictures seem to ask, ‘How does she get into these places?’ and sometimes, ‘How does she get out of them?’ It is almost as if there is something of performance art involved. Getting access to places was somewhat easier in my earlier work because I could often see things from the street. Also, I could find subjects listed in the telephone directory. The yellow pages seem like an archaeology of the present and I continue to find photographic ideas in them. In my recent work the process is more complicated because the locations are often behind several doors, hidden from the street. I spend more time now searching in technical journals and on the Internet looking for subject matter. Once I have an idea that something might be interesting, I make telephone calls and write, ‘explaining’ my work to get permission to visit. The finished photographs depend on the generosity of strangers. I see the finished pieces as collaborations of a sort.

The process is both exhilarating and frustrating. Exhilarating because I never know what I’ll discover behind the closed doors, worrying because I am never sure that the people in charge will grant my permission to photograph.

MH: What is your initial approach when you enter these places? We know that you intervene very little. But do you always have a precise idea of what you want to obtain? Or do you allow yourself to be guided by certain unexpected factors? What are you drawn to first?

LC: My approach varies. I often don’t know what to expect or what I’m looking for other than having a hunch about what I might find in a particular category – spa, classroom, or military installation. Sometimes I’m looking for something. Sometimes I have a vague idea of what I might find only to discover there is nothing to photograph. At other times I’m excited because it is better or different than what I had expected. My first hope is that I’ll be given enough time and able to work on my own with no one to entertain or be bothered by. This is seldom the case and I often have work around lunch and coffee breaks, with supervision.

What I’m looking for is something political or conceptual, something incongruous or pathetic. It’s difficult to articulate precisely what I am drawn to apart from a certain sense of strangeness, incoherence, sadness or an asphyxiating order. I am drawn to things being not quite right and to how various sorts of flaws poke holes in our dreams and ideologies. I am interested in things that are the wrong size or color and in symbols of suspect sentiments. I am also interested in hardware – air ducts, electric outlets, light fixtures, heating devices and the like, which take on exaggerated importance, sometimes even a symbolic dimension. I intervene very little, although I don’t have an ethic about shifting something or removing this or that because it is distracting. I am perfectly willing to clean up a little formally to make things sharper. On the other hand, I don’t bring objects with me (I have enough to carry with the equipment and film holders) and I prefer not to interfere with what I think is the inherent meaning or characteristic of the places I find. Interestingly, in the 1980s a critic for the Village Voice reviewed my show at PPOW gallery in New York suggesting that the sites I photographed and the objects in them were somehow constructed by me in a studio. While I almost always feel as if the places I photograph could not be true, in fact I photograph them more or less as I find them.

MH: Although you exhibited contact prints in the 1970s, there was a shift to large format pictures in the 1980s. What motivated this change?

LC: I made the move to larger prints for various reasons. But first I should say why I began making contact prints in the early 1970s. My first photographs were contact prints from 5″x7″ and 8″x10″ negatives because it struck me that the work would be more modest and more in keeping with the ideas about art and society that I felt my work was addressing if it were small. What I discovered in the mid-1980s was that I had other things to say – ideas that could be better addressed by a larger format. Also the contact prints lent themselves to being misunderstood as documentary in intent, which was not how I saw them. So I began to enlarge the prints, first to 16″x20″ and later to 30″x40″ and 40″x50″. I realized that my early beliefs about art and ideas could be seen as compromised but I felt that the pictures nevertheless needed to be bigger. Once sufficiently enlarged, they became more spatial and I also heightened the dimensionality of the pictures even more when printing them. Once I enlarged them, the viewer could imagine physically entering the spaces depicted. My feeling was that if I could implicate viewers physically, it might be possible to implicate them psychologically as well and thus intensify the disturbing aspect of the pictures. But now, when I look at the contact prints, I find I like them very much, precisely because they demand viewing at close proximity. I have recently exhibited them alongside the larger prints and have found people finally recognizing the conceptual nature of this early work. They seem less inclined to dwell on the subject matter.

MH: Do you work in series or do you see your work as a set of images, concepts and time interlinked with one another, with no beginning and end? Is the idea of chronology important to you?

LC: I have never actually worked in series though it may seem that I do. Over the last thirty years or so I have worked on a number of categories or types, perhaps twenty or thirty different ones, in a way that has led some viewers to think I made all the pictures in a particular category at the same time. This isn’t so. I continue to photograph in various categories, although some have dropped out over the years. I cannot imagine that I will ever photograph another living room or men’s club. I think I exhausted them. On the other hand I expect that there will be more classrooms, laboratories and spas. But even when I was photographing living rooms, they weren’t all made at the same time. Nor did I consider them part of a series. Likewise I don’t consider the laboratories, spas and military installations as belonging to a series other than an ongoing project of making photographs for more than thirty years. On occasion, the spas or laboratories have been exhibited together. That has also led people to believe they were made as a series.

Your question about whether I consider my work as a chronology is difficult to answer. For a long time I resisted putting dates on my photographs because it seemed to me that it didn’t make any difference if this or that interior was done in the 1970s or thirty years later. This was a bone of contention with dealers and curators. My response was to suggest that furniture and appliances are a kind of archaeology of a place and time. For example, my photograph of a living room with beanbag chairs, Professor’s Living Room, could only have been taken at a certain time. The design of television monitors, computers and other paraphernalia are also dead giveaways. I’d say the early work could be distinguished from later work by the different smells they conjure up. I would link my early work to smells like wet dog hair on shag carpet, ashtrays filled with cigarette butts, empty beer bottles, hair spray and baby powder, and I’d associate my later work with smells of electric wires, chlorine, gasoline, steel, formaldehyde and duct tape. Finally I caved in under pressure by the publisher of my book, No Man’s Land, to date my pictures and establish a traditional chronology. I was not unhappy supplying dates, if only approximate ones, partly because I was becoming more territorial and wanted people to realize that I had done something before someone else had done it. Dating the pictures was the only way to insure this. There are of course other ways to establish a chronology. The living rooms, banquet halls and men’s clubs disappeared from my repertoire in the early 1980s and were replaced by classrooms, laboratories and spas. Contact prints were replaced by enlargements in the mid-1970s and I began to work in color in the late-1990s. In addition there are various stylistic shifts from early to late work.

MH: People tend to associate your photography with black and white work. And yet a good number of your pictures are in color. Why do you think that is? What role does color play in your pictures?

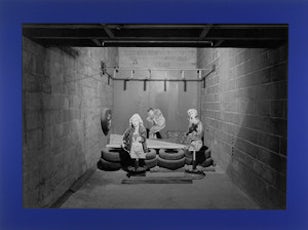

LC: What you say goes both ways. I worked entirely in black and white until the late 1990s but the frames were colored. In a recent retrospective of my work at the National Gallery of Canada and the Musée de L’Élysée, Lausanne, I exhibited black-and-white work alongside recent color work and was pleased and not surprised that viewers often didn’t realize when they moved from one to the other. The photographFactory has a flesh colored frame and people frequently remember it as a color photograph perhaps because the androgynous dummies in the picture are flesh-colored. Another picture, Police Range, has an International Klein Blue frame. It echoes the temperature of the room and the comic-book color of the targets in the picture. The odd thing is that when my black-and-white work is exhibited alongside more recent color photographs, many viewers remember the work as being in color. The introduction of a single color in the frame seems to indicate the dominant color, mood or temperature of a room and I felt for a long time that providing any more color information would only confuse things. That was why I resisted color. In the late 1990s, however, I started working in color. I decided to let go of the idea of getting the color right, and I became interested in how color film subverts the psychological weight we accord things and in the many ways color film gets things wrong. I exhibited the color work for the first time in 2000 at PPOW in New York and a year later included fifteen color photographs out of ninety or so pictures in No Man’s Land.

MH: So the frames are very important to you?

LC: The frames are extremely important to me. Quite early on, I decided that if my photographs were going to be framed, I should take responsibility for designing them rather than leaving it to the museum to frame them in a house style – blond wood or whatever. My coming to photography from sculpture surely played a role in this. It struck me that the frame should echo what is going on in the space I photographed – the color, temperature, materials or something else. I use Formica (a plastic laminate) mainly because it is often used in the decor of the places I photograph and it echoes the surfaces one finds in public and private interiors. It is also a very beautiful material. In most of my black-and-white photographs, there is a particular color or faux texture that more or less carries the psychological weight of the interior, at least how I remember it. For example a photograph of a military installation is framed in an army green Formica because of its association with camouflage and because it conjures up the color and smell of canvas.

In my color work, the frames are more low-key. I continue to use a plastic laminate when framing my color photographs but avoid color or faux surfaces. The various grey tones I now use are intended to resonate with the color temperature in the photograph.

MH: References to architecture, sculpture and installation (spatial construction, Minimalism, Conceptual art, attention to objects, etc.) are undeniable in your work, as are your many allusions to painting (viewpoint, perspective, light, mimesis). Are these references to art history the primary impetus behind your work? What role does photography play for you as a means of expression? Do you consider this medium to be the most apt means of condensing all the modes of expression mentioned above?

LC: I’ve resisted the idea of spelling out influences. Partly this is because the list would be very long. But mainly it is because I think cataloguing influences oversimplifies the work. I have never had a list of necessary ingredients in my pocket – a little bit of Minimalism, a little Pop art, some Conceptual art, some Dada. That doesn’t square with what goes on. To my mind it is more useful to consider the context in which I took the pictures. It is obvious that each of us works in a particular context but I think it is often overlooked and rarely spelled out adequately. As Marx pointed out, people make their own history but under conditions given and transmitted from the past. It is a two-way street. In my case Pop art, Minimalism, Conceptual art, installation art and the ready-made provided a context in which I made the move to photography. These all find their way into my photographs, sometimes as quotations, sometimes as funny coincidences. But they are always transformed. The interiors I describe as ‘ready-mades’ are tied to a particular moment in art making. It would not have made sense to talk in these terms twenty years earlier.

As an aside I might mention that in the early seventies before I began taking pictures, I considered transporting sections of rooms to museum settings. The idea was to take a corner of an interior I found – a table, a Naugahyde chair, a goose-neck lamp and linoleum floor – and to transport them to a museum, much like the pieces I saw in the eighties of the work Guillaume Bijl did with entire rooms. The installations would have been like photographs in three dimensions. In the end I opted for photography because it seemed a more appropriate and modest means to condense the sort of information I was drawn to.

Turning to your question about whether photography is the most apt means for doing what I set out to do I would say I felt photography was the appropriate medium given the ideas I wanted to address and the conditions of the time. It struck me and other artists working in the early 1970s that it was a medium without pretense. It didn’t come with the heavy art historical baggage of painting and sculpture and I thought its modesty and directness would make my interference as an artist less visible. Similarly, my decision to use a view camera was connected to my wanting to record a piece of the world with immaculate detail and to let the objects speak for themselves.

MH: Your representations are very ambivalent: they convey spaces that are simultaneously baroque and minimalist, ironic and austere, real and fictional, stable and precarious, balanced and disconcerting, inhabited and vacant. These spaces appear more real than reality. They are impossible, or even abstract, places of sorts. How would you account for these dichotomies? Where do you situate your level of intervention in this regard?

LC: It’s an odd thing but I’d like my interventions to seem neutral. I want the viewer to be deceived into thinking that all is normal, that this is how things happen to be when obviously it isn’t. From my first photographs I felt that if I could seem to remove myself from the making of the pictures, it might permit the subject matter to speak for itself. Trying to conceal one’s presence is often easier said than done but I have made a big effort to make my photographs seem as if they mysteriously appeared. This is one reason I use a view camera, a moderately wide-angle lens and unaffected lighting. It is also why I aim for unremarkable compositions and finished prints that look almost too perfectly balanced. I want to set up a situation where the viewer might concentrate on the puzzling nature of what is depicted rather than on how the picture is made. These devices conspire to make the interiors I photograph look real, yet impossible, stable and unstable, assured and vulnerable, all at the same time. Ideally viewers should feel like they are seeing something for the first time. Visual clues should strike them as more wrong than right. Things should appear to be the wrong size and the objects and the spaces between them seem too big or too small. Also these interiors should seem to have been designed with something other than convenience or comfort in mind.

Let me try to explain things another way. I think that Thomas Demand’s photographs of his constructed interiors often look more convincing than my pictures of similar places. In one way this seems crazy. A photograph of a hand-made interior looks more realistic than a photograph of a real place? But there is something about constructing an interior by hand, making allowances and corrections, which result in a photograph of it looking more plausible than a photograph of a similar space from the world. His constructions look doubly true because we are looking at a photograph of them. By contrast, my photographs of unaltered interiors appear to have been strangely constructed. We think they couldn’t be true, that they must be tampered with, which of course isn’t the case. The difference, perhaps, is that Demand seems more interested in ‘getting it to look right’ while I am interested in showing how ‘wrong’ it is.

MH: You have already mentioned that you are not a documentary photographer. What do you think is the key distinction in your work?

LC: While it’s true that I appropriate a documentary approach and many of the formal strategies of documentary photography, my work is not documentary and was never meant to be. My interests lie elsewhere. I want to make pictures that are conceptual, social and political, pictures that are connected both to the real world and to art but without being documents of either. I sometimes think that what I am doing is documenting an idea I have in my head and trying to link it to this or that bit of the world. Also unlike documentary photographers, I am not mainly concerned with documenting places and often don’t make a photograph in a place even if I have gained access. I might make a long trek to a location and decide there is nothing I want to photograph. I don’t think documentary photographers would allow themselves to go home empty-handed, as the goal of their project is to document something, come what may.

MH: The suspicious neutrality of your images seems to belie a critical intention. Should we see any sort of latent message in your work as a whole?

LC: There is a critical edge to my work but I prefer quiet persuasion to shouting at people. I have no interest in preaching or in being didactic. This is why I opt for a veneer of neutrality and prefer to underplay the critical edge in my work. At the same time, I would stress that critical intent is only one of a number of things going on. In some pictures the details and objects in the photographs function as symbols of manipulation and control. But even in these pictures, there is usually something absurd or funny to counterbalance the critique. That is very important to me and I hope the humor enriches the work without masking the critical edge. It’s a difficult balancing act. Actually, I feel closer in spirit to Jacques Tati and Fluxus than I do to Michel Foucault. I would not deny that some of the photographs and the language I use to describe them might suggest otherwise but that’s how it is.

– Mona Hakim

Footnotes

-

Prepared for a conference organized by Vox, Image Contemporaine/Contemporary Image, Montreal, January 2004. Revised for publication by Lynne Cohen and Andrew Lugg.