Although Simone Forti’s influence on the field of postmodern dance is regularly acknowledged, her contributions to early 1960s US minimalism and conceptualism are frequently omitted.01As has been argued, the emphasis on the conceptual brought with it the myopic relegation of ‘feminised’ practices, such as dance and choreography, to the status of the uncritical.02More recently, however, the turn to performance has prompted a reassessment of her oeuvre within art historical accounts, as her retrospective at the Museum der Moderne, Salzburg in 2014 and the 2015 acquisition of herDance Constructions (1960–61) by the Museum of Modern Art in New York demonstrate. 03Bryony Gillard and Louis Hartnoll spoke with Forti about her wide-ranging influences on the occasion of a recent performance of her work Illuminations (1971–ongoing), developed in collaboration with composer Charlemagne Palestine and shown as part of her solo exhibition ‘Here it Comes’ at Vleeshal in Middelburg. 04The interview was conducted on 2 April 2016, and included the participation of artist and writer Sarah Boulton and Vleeshal director Roos Gortzak.

Louis Hartnoll: With tonight’s performance as background, we wanted to start by talking about the role of collaboration in your work, and how that has unfolded over time – particularly how you found it collaborating with Charlemagne [Palestine] and what it means for you to return to a work first presented in 1971. What impact has that slower and longer process had on the piece?

Simone Forti: There were many years when we didn’t work together, in fact now there’s a resurgence of opportunities to work together. I was surprised and, in a way, not surprised that we were able to get right back into it. And it’s very much the way it used to be. Charlemagne and I first met at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) in 1970. I knew that I wanted to find a musician to work with. At CalArts there were a lot of beautiful spaces and I asked a couple of musicians: ‘let’s do a session and see if we hit it off’. With Charlemagne it was immediately clear that we really liked working together. We started spending a lot of time in this one room, which had a really comfortable wooden floor and a beautiful Bösendorfer grand piano; we called it ‘The Temple’. As we do now, he was working with harmonics and I was, in a sense, working with harmonics of movement. I was running in a circle and, according to the slightest leaning my trajectory would change, or just balancing my arms in a different way would pull me into and out of the circle. It’s very much like being on a bicycle: you turn by leaning. Playing with momentum, with centrifugal force, with centripetal force. So there was something similar with the way Charlemagne was working with sound waves and I was working with the physical dynamics of a mass going through space. We were both kind of mystics, especially Charlemagne – that’s one aspect of it. And so the work had a mystical exploration of physical properties in the universe looked at for beauty.

LH: And what has it been like returning to some of those early moments with Charlemagne?

SF: What’s it been like? Well, I’m a lot older and so is Charlemagne. And I have Parkinson’s. So far the work is still there. I was going to say I worry more about it, but I worried about it then too. And I’ll sing a little song that Charlemagne sang to me one time when we were getting ready for a performance:

Simoney, don’t worry.

You will dance and sing allright.

Bryony Gillard: Thanks for this, Simone. Following on from that, and from something Louis and I have been talking about, is the role of friendship within collaboration, and different types of intimacy that are important in shaping the terms of collaboration.

SF: Charlemagne and I have always been like brother and sister. Very close. Charlemagne would come to dinner at my parents’ house, my mother would make pasta and we would drink red wine. We had a strong friendship. In the 1970s I was married to a musician and graphic artist, Peter van Riper, and that was a very different relationship. We travelled together and did tours together. That work was based on other material, he was a saxophone player and also played many other small instruments. At that point I had been spending a lot of time in the zoo watching different body structures that resulted in different movement, and trying some of it on my body structure – understanding my movement in certain ways by studying movement in other species. I was also looking at some mythical figures, like the Egyptian god that’s part bird. I also spent time in the Egyptian Museum and the Natural History Museum in Torino, looking at animals through the eyes of another culture. So I’m always working with improvisation with a point of reference that I’m studying, and with Charlemagne it was the dynamics of the circle.

BG: I am interested in the relationship between improvisation and different types of study, such as the intense and rigorous approach to research that you describe, in terms of balancing between different modes of thinking/being.

SF: I don’t know. Improvisation is very rigorous, because you’re working with ideas. I think there’s a common idea about improvisation, but as I listen to your question and I do what I need to do to give a good answer, I’m improvising. So I’m calculating, figuring out, sensing the situation, keeping in mind what you need. There are a lot of elements that go into it, whether I’m improvising in an interview or dancing. So it’s really not so different to research.

Roos Gortzak: The title of your 2014 retrospective at Museum der Moderne in Salzburg, ‘Thinking with the Body’, is also informative in this sense because the research also comes through bodies and body structures.

SF: Well, there were, for example, animals that I had observed in the zoo, certain individuals that would develop some kind of movement game or movement practice. Bears will do that. Elephants might do that. Primates will do that. I doubt if turtles do it, but I don’t know. I did start out by looking at their body structures: they’re built like that, they move like that. Then I would discover certain events that looked like a movement game, especially in the younger ones. Like a young chimp that found a little hole in the ground, put its finger in the hole and leaned out and ran around it. It was like a merry-go-round. Or, in a very different situation, I arrived in the Bronx Zoo, which has very large enclosures for animals that are endangered, and there were some Père David’s deer. Most of the herd were at one end of the enclosure, and at the other end there was a female with a baby. I was lucky enough to arrive soon after the baby had been born because I suddenly saw the biggest deer in the herd – the male deer – gallop across the field, leap into the air, land right where he had jumped up and then trot away. It looked to me like the male had given the impression that the baby was going to get jumped on and crushed, but it was just theatre for the baby. It was an introduction into life. So I saw several things that were a way to make life in prison a little less heavy, certain games that had been invented, and that interested me. I thought that that was the roots of dance: every culture develops dance in its own way, and it develops it in very sophisticated ways, but there is always a basic principle of playing with movement, being able to find something that you can come back to as a kind of game, and learn it from each other.

I spent a lot of time in the zoo watching different body structures that resulted in different movement, and trying some of it on my body structure – understanding my movement in certain ways by studying movement in other species.

LH: What I find interesting and difficult with the animal studies, particularly when you’re observing them in the zoo, is that there are some obvious constraints that those animals and their behaviour suffer from – that their movement is the bodily, traumatic absorption and response to these impositions. I wondered whether you had reflected on those games as a way of responding to such constraints? Or whether improvisation within confinement was something that intrigued you?

SF: Well, I was aware that animals in the zoo were kind of in our culture, they had to adapt to something about our culture. For instance, I remember the grizzlies had quite an elaborate game, and seemed to be very aware that when they started to play people would come and watch. And so that helped pass the time. But I also felt badly, especially for certain ones. When I moved to Vermont I thought ‘now I’ll see some bears, some moves’, and I soon realised that when you go into the woods they see you but you don’t see them. You really need a lot of patience and a lot of skill to see animals in the woods. But I started doing a lot of gardening. I got very interested in the worms and the beetles and the whole animal life that’s within the earth and the garden.

LH: Maybe we could turn to your book Handbook in Motion (1974) because it’s such an intriguing document. What I’d like to suggest is that it’s simultaneously a generous document, because you’re discussing a lot of life and your thoughts and responses to your practice and others’ over time, and also a vulnerable document, because you do bare so much in it. I was wondering what it was like to publish it and what was its reception in the 1970s?

SF: Kasper König invited me to be part of the Nova Scotia Series that he was publishing very much based on my Dance Constructions. By then, I had gotten back to improvisation. I had a very different book in mind. I had been to Woodstock and spent a year in that drug culture. I had pretty much become a hippie. So with Kasper we had quite a struggle. I think the book came out more interesting than either what he had in mind or what I had in mind because I had to find a bridge and some meaning to having changed style, let’s say.

BG: I wanted to talk about the altered sense of chronology in Handbook, in relation to how (in the book) you describe moving from the Dance Constructions to new ways of working – turning away from closed systems to an open system and working with open structures. I am curious that there is a kind of a chronology in the book, but then, at the same time, it feels like things are nonlinear.

SF: In the third edition, which I published myself with the help of Contact Quarterlyjournal, I added an introduction which explains that the book starts in the middle, then jumps to the first part and finally jumps to the last. So the chronology is pretty clear, it’s just B-A-C. While I was in Nova Scotia working on the book, Emmett Williams arranged for me to have a room with blank walls and he said, ‘Tape each page to the wall in sequence and you can move them around and find exactly what sequence you want.’ By then I already knew the blocks that were going to be B-A-C, but then there were the drawings, and the little drawings at the beginning. So that gives the ordering of the book a more visually chosen, rather than a literary, approach – the sequence of some of the images.

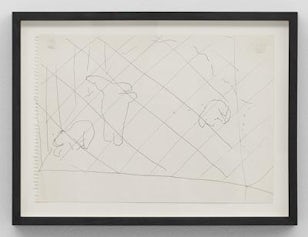

BG: I wanted to also ask you a question about your drawings. When you first showed your drawings in the Salzburg retrospective you said that you often made them at times when you were going through difficult things in your life. 05 I’m curious to know more about your approach to drawing, how you use it and if it has any relationship to dealing with pain or trauma.

SF: I make drawings in my notebooks often as an expression of what I’m thinking about, trying to figure out my thoughts – especially if it involves strong feeling, I might draw. In terms of drawing outside of my notebooks, a lot of my watercolours happened when I took some classes at Hunter College in New York. I was in a marriage and wasn’t doing my own work, and I thought I would go to evening school and get a bachelor’s degree. It turned out that even though I had changed my field of study – I had changed it many times – I was always taking one or two art classes just for myself. So I went to Hunter College and majored in visual arts. Because I was in school we were making drawings and paintings. There was a stack of paper on the table up front that we could just take. It was a difficult time in that marriage, and I made drawings that expressed that. Recently, I go through periods of getting kind of depressed in the afternoon, I think many of us do. It was especially heavy for a while, which possibly is also a manifestation of the Parkinson’s. I got a request to donate a drawing to an art organisation in Los Angeles and I thought ‘OK good, this is a chance to make drawings’. I thought ‘well, I’ve been feeling a sense of desolation, almost like my life is a frame around this sense of desolation’, so I decided to find a frame and do a rubbing of the frame. I went to a second-hand goodwill store and I found just the perfect frame. I made a series of rubbings of that frame and they went into my show at The Box. I’m very happy with those drawings. When you see the drawings they’re not sad drawings, they’re quite lyrical in fact.

BG: I was wondering about your idea of the dance state – the state you enter when you’re dancing. I’ve been thinking a lot recently about the idea of being in a position, in one’s practice, of constant movement: continually shifting and self-reflecting on ideas and positions and ways of being.

SF: Well, the dance state. It’s like sometimes when you have dinner with someone and the conversation really gets going, you feel very inspired – maybe you have a glass of wine or two – and ideas really start to come. Or you might have dinner with the same person and you really struggle to think of things to say. So the dance state is when it’s happening, when ideas are just unfolding. When things feel right. It’s an interesting question about how it relates to your general thinking about your work. Sometimes when you’re exploring some new material that you are very excited about or you’re discovering new things, the discovery unfolds. It’s mysterious, though, when it just happens. Or when you have to work hard for it. Sometimes in the middle of a performance I’m thinking ‘Well, I’ve been doing this for a while; I’ll have to do something else. What? I used to do that, I could do some of that.’ I think that when you think about your work that’s one way of working on it, different from when you’re really doing it. The moment of doing is part of working on it, and the moment of reflecting is another part of working on it.

Footnotes

-

See, for instance, Yvonne Rainer, ‘An imperfect reminiscence of my studies and the beginning of a career and contingent events’, in Work 1961–73, Halifax: Press of Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1974, pp.1–10.

-

See, for instance, Virginia B. Spivey, ‘The Minimal Presence of Simone Forti’, in Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 30, no. 1, Spring/Summer 2009, pp.11–18.

-

For information on the research documentation and acquisition of Dance Constructions by MoMA, purchased during the preparations for Forti’s presentation at Vleeshal, see Nancy Lim, ‘MoMA Collects: Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions’, MoMA, 27 January 2016, available at http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2016/01/27/moma-collects-simone-fortis-dance-constructions.

-

‘Here it Comes’, Vleeshal, Middelburg, 30 January–3 April 2016.

-

Astrid Kaminski in conversation with Simone Forti, ‘Join the Movement’, Frieze, 17 December 2014, available at https://www.frieze.com/article/join-movement.