Jim Isermann: I’ve been trying to recall my first encounter with the work of Sister Mary Corita. Growing up Catholic, I’m sure I first recognized the graphic style permeating banners and newsletters that infiltrated the church around the same time as guitar masses. It wasn’t until I moved to California in the late 1970s that I put a name to that style. The first Corita I acquired was her decidedly secular work from 1963, International Dining With Spice Islands, which I found in a Palm Springs thrift store. It was a boxed set of 10 recipe booklets (nine sets of menus, each from a different country) featuring her cover art.

What is your first memory of Sister Corita and your first acquisition?

Pae White: My first exposure was in high school, in the hallway of a friend’s house. They must have had twenty or thirty of them. All I can remember was that the hallway was so dim that you couldn’t read any of the writing, which really seemed crucial to the work. Despite the darkness I still got a feeling for the loopiness and transparency of her work.

Years later I saw some Mike Kelley lithographs and it seemed like he had lifted her progressive, yet poignant style. In place of words like ‘free’ or ‘love’ or ‘man’, he inserted the text for farting noises.01 He was definitely poking fun at the sentiment, but I also think he was paying a small homage and possibly commenting upon how easy it was to hijack this look for means so far from the original intent.

Why do you think there has been such a revival of interest in her work?

JI: That’s a good question. The first inkling I had that she was coming back into style was in the mid-1990s, when a friend in Stockholm wanted me to find the Corita book with the box of thirty-two offset prints. I bought two of them, one for him and one for myself. That was around the same time that I collected all the Corita prayer books. You could get them for practically nothing at used bookstores online. I thought it was just a more esoteric interest in all things 1960s or perhaps something quintessentially Southern California, since this was Corita’s home during the best years of her work. But that doesn’t really answer why. What do you think?

Have you seen the documentary that the local PBS channel, KCET produced? Eva Marie Saint, who I guess was a collector and a personal friend of Corita, narrates the piece. It’s kinda sappy with goofy music and everything, but has amazing archival footage. I’ll never forget the clip of Corita on the Johnny Carson show…02He’s talking about how her work is upbeat and happy and says something like, ‘How wonderful it must be to be you!’ And she looks just awful and says she is an insomniac. I was so struck by that disconnection between her and the perception of her work.

PW: I did not see the KCET documentary. But I seem to remember an image of her on the cover of TIME magazine. Maybe it was LIFE?03

I think the rediscovery of her work probably comes out of a general resurgence in the popularity of modernist furniture and designed objects from the 1950s, 60s and 70s. It’s like the illustration work of Andy Warhol: you’ve seen the style but you don’t really know where it came from until you have seen his original line drawings. I think Sister Corita’s style was easily adaptable into textiles, graphics and advertising. In many ways the revolutionary message of her particular aesthetic, merged with secular concerns and redelivered on non-secular terms, was completely lost when it was reduced simply to pattern.

I think it all comes down to the suitcase.04 I wonder if she felt that its production was a success? Perhaps she was comfortable with the application of her message into pattern and then reestablished on an everyday object with poetic references? What do you think about the mysterious suitcase … other than the fact that you’d like to own one?

I bought my first Sister Corita piece in 1998 or so. I found it at an antique store hung almost to the ceiling. Because I recognized it as a Sister Corita I felt obliged to rescue it for $180, which was steep for me. It was a signed serigraph of four large, lazy, abstract blue and purple shapes overlapping. It had a large wood frame that was painted blue to match one of the shapes in the composition. There was a clipping of her obituary on the back. It also had a big stain on it but I felt the stain kind of duplicated the organic quality of the abstract shapes. I know you would never buy anything with a stain on it. I probably wouldn’t either, now.

JI: God, the suitcase. I still dream about it sitting in that vitrine at the Hammer.05

It’s weird that her work didn’t translate as a mass-produced functional object like the suitcase or as sheets and towels. Do you think because it was already a kind of mass-produced art? I mean, come on, we love it, but was it really taken seriously as high art? I don’t think so. She was an incredibly influential graphic designer but in the art world she was relegated to the religious ghetto. And her images were (like Vasarely) available as signed limited edition serigraphs, boxed offset prints, posters, postcards, greeting cards and inspirational books. Something for every price point.

PW: I think you may be right about the ghetto aspect. Maybe her aspirations were greater than the Immaculate Heart gift shop?06 Perhaps her sadness came from being reduced to a novelty or an oddity and the Johnny Carson appearance reflected that? Sister Corita one week and lemurs the next.

I still think her aesthetic was pretty far reaching. It’s interesting that a print with a loose handwritten message still reads to me as acting up.

Do you think her work has had an influence on your practice?

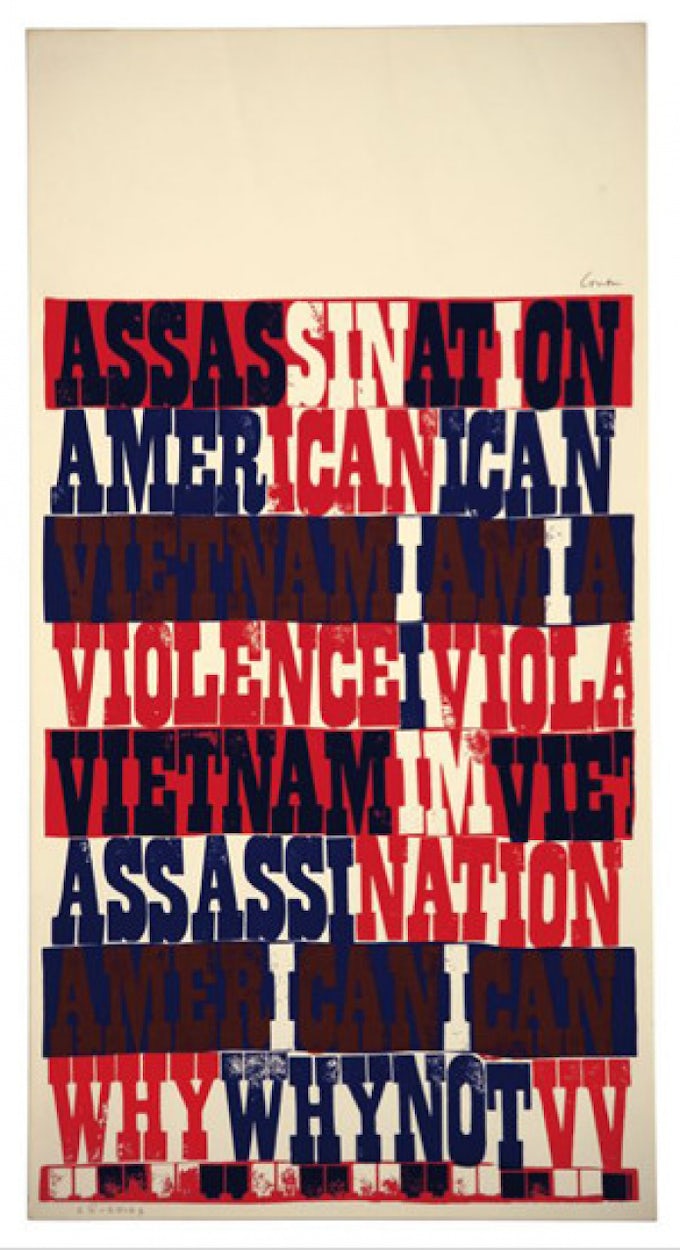

JI: Yes, I love that it was so available. As far as my practice is concerned, I guess I am always really impressed when an artist can be so totally of the moment – meaning that she was able to lift text from billboards, advertising, packaging and grocery store posters and turn it into her imagery, without losing the source. Her work from the mid-1960s encapsulates that time: Warhol’s Brillo boxes, women’s lib, general unrest and, in the face of it all, a feeling of taking back power. It seemed to all come together for her. Then in the 1970s her work kind of faded and became soft and not so Pop, strangely like Warhol too.

The new book, Come Alive!, suggests that Sister Mag was a driving force behind Corita while she was still at Immaculate Heart.07

Have you heard that before? And how do you see it compared to your work?

PW: Corita has had a very big impact upon my projects, both past and present. It isn’t so much the protest qualities but more the ‘talk of love’ aspect that I feel is so revolutionary. It is unapologetic and completely sincere. I feel this is also true of the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres. The candor with which his work speaks of love and relationships appeals to me because I find it absent in so much contemporary art. Even though Corita talks of LOVE in relation to GOD, it is easily transferable to discussions of other kinds of relationships and their complexities.

I even lifted a phrase directly from a Sister Corita serigraph in my first solo exhibition. It was a large freestanding transparent billboard which said ‘Love, Uneasy, Balance’ in an abstract, graphic way. I just wanted the awkwardness of the word ‘love’ in the exhibition in some form, even if it was upside down. Even just recently, for Skulptur Projekte Münster, I’ve titled my projects ‘To Münster with Love’.08 I felt that the relentless ambition of the project reflected Kasper König’s deep love for the city of Münster. I wanted to tap into this by engaging small situations within the city such as marzipan shops, making small sculptures and bell towers playing love songs.

Somehow, from what I’ve read, I get a sense that Sister Mag may have been the inventor and the undoing of Corita. I wonder if she pushed her to do the suitcase? At any rate, something or someone drove Corita to the point where the quality of her work really took a dive. It seemed to get almost lazy, or even overwhelmed. There was a total lack of nuance, both aesthetically and conceptually. Maybe she felt it was time to be more direct and just use black letters and solid colors? I think the type itself even changed to something more corporate, like Helvetica. On the other hand, this transition could have reflected the corporate nature of the 1970s. As you were saying, she really was of the moment. Sadly, I think she developed one of the defining aesthetic tones of the 1960s, but then became a mere a reflection of trends in the 70s. What do you think changed for her, or do you think there was a shift in her output?

JI: Hold it, I LOVE Helvetica. She dropped the found typography and just lazily scrawled everything in the 1970s. I really like the way you think about your work in terms of sincerity. I never think of my work as being ironic, yet it’s often misinterpreted as such. I connect to the melancholic side of Corita more closely. I also see this in the unbearable sadness, or reverie or sense of loss embedded in some of Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s work.

I got the feeling from the KCET documentary that there was another reason Corita left the sisterhood. If I read in between the lines correctly she was in LOVE. And it was unclear whether it was unrequited or if the object of her affection would not leave the priesthood. So maybe it wasn’t God she was professing her love for. Either way it seemed to feed into her estrangement not only from Los Angeles or Sister Mag, but her support system in general. Even though she was painting that water tower near Boston, designing the US Love postage stamp and reaching a bigger, broader audience than ever before, it seemed so antiseptic, isolated and disconnected.09 And I guess as equally bland as a lot of corporate 1970s things.

One of the aspects of her life that I didn’t know about until seeing Come Alive!was her friendship with Charles Eames and Buckminster Fuller.10Can you imagine having Eames come to your class, or taking your class to the Eames studio and house? That really put her in a totally different context and again totally connected to what was going on.

PW: I wonder if sincerity in art making can be the most subversive stance? I try to enlist this: not necessarily to be subversive, but more to be frank. It seems to throw off the viewer. Unfortunately, many viewers approach art through a lens of irony, but they have been programmed to view it this way. I feel that in the contemporary art context the interest in Corita’s work comes out of a perception of irony but in fact she was a nun talking about love and God… I mean, how ironic could that be?

JI: Yes, SINCERITY definitely rules. The ironic thing is that she entered the sisterhood to escape reality and people, and never wanted to teach, and she kind of got pushed into it. And despite that, from what I can tell, she was a great teacher. Have you seen her book on teaching? It was published after her death and has late cover art of rainbow-colored swathes. It really shows the enthusiasm that she shared with Eames for folk art and crafts – an enthusiasm that wants to believe that anyone can be creative and uplifting. It is a sincere belief in optimism that is really incredible and almost impossible to imagine today.

PW: The book is called Learning by Heart, published in 1992.11 I actually bought it last month. It seems to really embrace loose ends. It would be interesting if someone were to try and implement this manual for an art class in 2007. Maybe we should do it at Riverside?12

As a fellow collector (and not just of Sister Corita) I have to ask: which Sister Corita piece would you like to own?

Mine would be one from Damn Everything But the Circus.13 It’s the one with the text ‘LOVE-DROPS’ with the engraved lion in red and blue. I’d kill for that. In fact, I know someone who owns it – I think I’ll e-mail him.

JI: Yeah, OK, let’s teach the book. There’d have to be a major suspension of irony and it would be amazing what today’s built environment would yield in terms of inspiration.

The one I’ve always wanted is wonderbread, with just the oblong dots and no text.14Hey, don’t you have that one?

PW: Sorry, no.

– Pae White & Jim Isermann

Footnotes

-

Mike Kelley did a series of drawings in 1988 patterned after Sister Corita Kent, titled Poetry Paintings. They were acrylic on paper, and showed coloured abstract shapes overlaid with juvenile poetry.

-

The clip shown in the documentary isn’t from the Johnny Carson show, but from a local talk show in Boston.

-

Sister Corita appeared on the cover of Newsweek on 25 December 1967.

-

Corita designed a prototype for a line of Samsonite luggage that never went into production. The prototype was included in the exhibition ‘Power Up: Sister Corita and Donald Moffett, Interlocking’, which took place between 6 February and 2 April 2000 at UCLA Hammer, Los Angeles, organised by Julie Ault.

-

UCLA Hammer, Los Angeles.

-

Sister Corita taught at the art department of The Immaculate Heart College, Los Angeles from 1946 to 1968. The college was founded in 1871 by the Spanish order Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. As a result of a conflict with the archbishop of the Los Angeles Archdiocese in relation to the directives of the Second Vatican Council, ninety per cent of the sisters chose to be freed from their vows in 1970 and organize as a non-profit, voluntary lay community – The Immaculate Heart Community, inspired by renewal within the church and the ideas ofpeace and social justice. See http://www.corita.org/incomunity.html

-

See Julie Ault, ‘The Spirited Art of Sister Corita’, in Julie Ault (ed.), Come Alive! The Spirited Art of Sister Corita, London: Four Corners Books, 2006. See http://www.fourcornersbooks.co.uk

-

Skulptur Projekte Münster 07, 17 June-30 September 2007, http://www.skulptur-projekte.de

-

Corita adorned the Boston Gas Company’s natural gas tank with a hundred-and-fifty-foot rainbow. And in 1985 the US Postal Authority published her Love stamp in an edition of seven hundred million. J. Ault, op. cit., p.49.

-

See J. Ault, op. cit.

-

Corita Kent and Jan Steward, Learning by Heart: Teachings to Free the Creative Spirit, New York: Bantam Books, 1992.

-

UC Riverside. Jim Isermann is currently Professor, Chair of the Art Department.

-

From Corita Kent, Damn Everything But the Circus, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970.

-

wonderbread, 1962, serigraph, 63.5 x 77.5cm.